Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

One common argument against mixing housing types and densities is that if housing type A (for example, townhouses or single-family homes) is mixed with housing type B (for example, condos), the neighborhood will somehow be “ruined” for residents of the less dense housing types. Last week, my new wife and I visited Chicago for our honeymoon. The most interesting street we visited, on Chicago’s wealthy Gold Coast, was Astor Street, just a block from high-rise dominated Lake Shore Drive. What is unusual about Astor Street is its mix of housing types. Although this street is dominated by large attached houses, it also has a few tall-ish buildings next to the townhouses, such as the 25-floor condo building at 1300 North Astor, the 20-story Astor Villas at 1430 North Astor, and the 27-story Park Astor condos at 1515 North Astor. Despite the tall buildings, this street felt like a quiet, beautiful, tree-shaded urban street. And the real estate market seems to agree: recent Zillow ads show a single-family house on Astor Street selling for over $2 million, and another one selling for over $3 million. By contrast, the average house in Astor Street’s zip code (60610) is valued at less than half a million dollars, and only 14.6 percent are worth over $1 million. Clearly, multifamily housing has not “ruined” Astor Street.

One common leftist argument against new housing is the “Red Vienna” argument: the claim that housing can only be affordable in places where the government dominates the housing market. Supporters of this claim like to mention Vienna, where (according to progressive lore) Big Brother builds lots and lots of super-affordable public housing, while the Big Bad Market is not involved. But a recent article about Vienna states that “one-third of the 13,000 new apartments built in Vienna each year are funded by the government and commissioned by the housing associations.” This means that about 8700 apartments are built every year by the private sector. In a city with 1.8 million people, that’s a lot. By contrast, in Manhattan (which has a comparable population) about 3000 housing units were built between 2014 and 2017- far less than Vienna. Even in Houston (which has a slightly bigger population) only 14,653 housing units of all types, or about 3700 per year, were built between 2014 and 2017. In other words, even if not a single unit of public housing had not been built, Vienna would still have built more than twice as many units as high-growth Houston, and about ten times as many as Manhattan. Vienna’s affordability is thus an argument in favor of lots more housing, not an argument in favor of NIMBYism.

Many readers of this blog know that government subsidizes driving- not just through road spending, but also through land use regulations that make walking and transit use inconvenient and dangerous. Gregory Shill, a professor at the University of Iowa College of Law, has written an excellent new paper that goes even further. Of course, Shill discusses anti-pedestrian regulations such as density limits and minimum parking requirements. But he also discusses government practices that make automobile use far more dangerous and polluting than it has to be. For example, environmental regulations focus on tailpipe emissions, but ignore environmental harm caused by roadbuilding and the automobile manufacturing process. Vehicle safety regulations make cars safer, but American crashworthiness regulations do not consider the safety of pedestrians in automobile/pedestrian crashes. Speeding laws allow very high speeds and are rarely enforced. If you don’t want to read the 100-page article, a more detailed discussion is at Streetsblog.

I’ve been enjoying the series Meet the Romans, and episode 2 really revealed what I love about many ancient Roman cities. I’ve been to quite a few, though often without knowing beforehand that they were ancient Roman cities. These include cities like Dubrovnik, Split, La Spezia, Florence, Istanbul, Budapest, and yes, Rome. The attributes I’ve come to love include: 1. very narrow streets, often not accommodating cars 2. countless 4- to 6-story buildings with a variety of units, from cheap tiny units to large family units with courtyards 3. built into the 1st floor of these buildings are tiny shops – everything from restaurants to banks to bakeries 4. in ancient Rome most housing units weren’t used for much more than sleeping – living was done in the city. You often didn’t have a kitchen, laundry facilities, or even a bathroom. The host Mary Beard tells about the horrors of these things (barely enough room to lie down, the danger of dark small alleys), but I think in a modern world they’d be wonderful (ok, keep private bathrooms). Walk to your job, spend time in a vast variety of restaurants or pubs, experience the feeling of a busy narrow street, chat with neighbors at a public park, and take your kids to relax and play at the public bath or let them play in a public square while you grab a cappuccino. This is heaven to me. The only reason most modern cities aren’t like this is because we force them not to be. We require minimum space for all housing types, design our streets for cars instead of people, limit the height of buildings in most places, and separate our retail from our living zones. The effect is to push the less-rich outward, separate us from other people, and […]

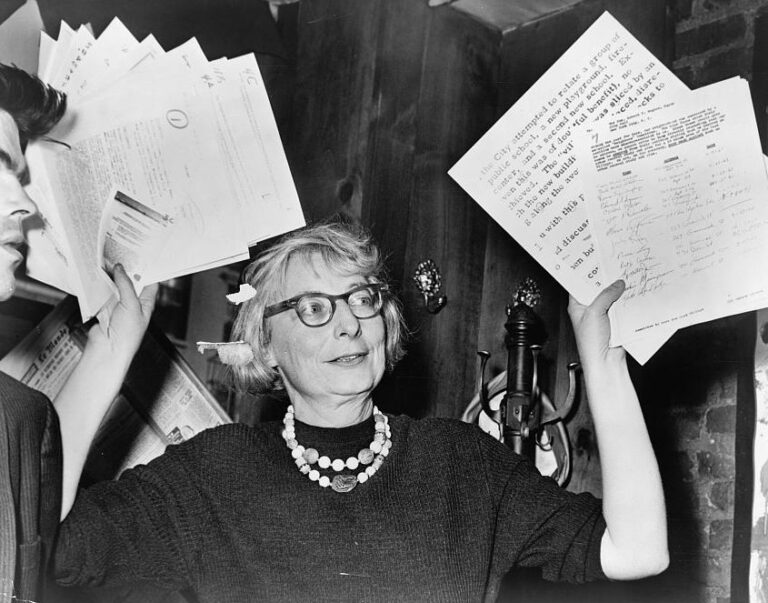

My guest this week is Sanford Ikeda, a professor of economics at SUNY Purchase and a visiting scholar at New York University. He has written extensively on urban economics, policy, and planning. Professor Ikeda introduced me to urban economics and urban planning when he gave a presentation on Jane Jacobs at a FEE summer seminar that I attended back in 2012. Here are a few of the topics we discussed in the episode: If you haven’t already, I highly suggest reading Jane Jacobs. The natural place to start is The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Her other books, including The Economy of Cities and Systems of Survival, explore topics ranging from economics to political philosophy. Professor Ikeda has written extensively on Jane Jacobs. You can read a nice overview here. If you would like to read more, click here for a paper he wrote on F.A. Hayek, Jane Jacobs, and the importance of local knowledge in cities. He is also a regular contributor to Freeman and Market Urbanism. We also discussed William H. Whyte’s famous documentary on public space, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. It’s well worth checking out. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

Even by the bizarre standard set by other fandoms, the fandom surrounding the Fallout video game series is weird. Where your typical human would rather spend a Friday night doing strange things like “hang out with friends” and “go out,” your average Fallout fan is likely spending his or her night asking “Could super mutants exist?” or debating the ethical merits of Fallout 4’s factions. In the spirit of this tradition, we wanted to ask: how realistic are Fallout’s cities? It’s worth first asking, does the Fallout universe even have cities? On the one hand, what we call “cities” in Fallout are quite small. In terms of actual visible inhabitants, even the largest of the Fallout cities—the urban area of New Vegas—has fewer than 150 known residents. Other large communities like Megaton, Rivet City, and Diamond City have approximately 50 residents each. The settlements that dot Fallout 4’s Commonwealth all have maximum populations of 21. Even the earliest known cities—take for example, Jericho—had estimated populations ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 in 9,000 BCE. There are two possible responses to this: First, we could be generous and look at Fallout concept art. After all, what we see in the virtual world of Fallout may fall short of the game designers’ vision of each city. Renditions of Megaton, Diamond City, and Rivet City depict cities with populations likely in the hundreds. In the case of New Vegas, concept art depicts a large city potentially supporting thousands of residents. Each is still smaller than even the earliest cities, but they are hardly the villages we experience in the games. Second, we could set aside population as an issue altogether. In The Urban Revolution, archaeologist V. Gordon Childe sets out 10 general metrics for urban cities. We won’t go through them here, […]

Over the last decade, Austin has exploded with a food truck revolution. They are so popular that temporary food truck installations on empty lots are mourned when the lot becomes ready for development and the trucks move on. But, taste aside, why do they do so well? What can we learn from them? 1 Food trucks as small business schools Restaurants are notoriously risky businesses to start. Many people start this way because food is their passion, but discover that making delicious food is only one of many components to running a successful restaurant. Food trucks are an opportunity to start your own restaurant at a smaller scale, and with lower costs. Budding restaurateurs can refine their menu, learn the ropes, and figure out whether they’re cut out for this industry without blowing their entire life savings. 2 Food trucks as proving grounds Lenders know that restaurants fail often; this makes them hesitant to fund new ones. By giving owners a chance to prove themselves and their ability to successfully manage a business, food trucks provide a way for lenders to separate the wheat from the chaff prior to making a large loan. This means some restaurants can get funding that would never have received it otherwise. Austin has seen dozens of restaurants that started as food trucks, before eventually finding brick-and-mortar premises. 3 Food trucks as regulatory hack Food trucks are regulated in how they prepare their food, where they may locate, and what kind of signage they can use. However, their regulations are both lighter and more directly related to their business than the regulations for brick-and-mortar businesses. If a food truck on a small lot with some picnic benches decided they would rather build a permanent building with indoor seating, they not only must still comply with the health and safety regulations the city requires; they would also have to provide parking. […]

“How to Make an Attractive City”, a video by The School of Life, recently gained attention in social media. Well presented and pretty much aligned with today’s mainstream urbanism, the video earned plenty of shares and few critiques. This is probably the first critique you may read. The video is divided into six parts, each with ideas the author suggests are important to make an attractive city. I will cover each one of them separately and analyze the author’s conclusion in a final section. 1 – Not too chaotic, not too ordered The author argues that a city must establish simple rules to to give aesthetic order to a city without producing excessive uniformity. From Alain Bertaud’s and Paul Romer’s ideas, it can make sense to maintain a certain order of basic infrastructure planning in to enable more freedom to build in private lots. However, this is not the order to which the video refers, suggesting rules on the architectural form of buildings. The main premise behind this is that it “is what humans love”. But though the producers of the video certainly do love this kind of result, it is impossible to affirm that all humans love a certain type of urban aesthetics generated by an urbanist. It is even less convincing when this rule will impact density by restricting built area of a certain lot of land or even raising building costs, two probable consequences of this kind of policy: a specific kind of beauty does not come for free. Jane Jacobs, one of the most celebrated and influential urbanists of the modern era, clearly argued that “To approach a city, or even a city neighborhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, […]

Last week, Tyler Cowen wrote that Los Angeles is the best city in the world based on several factors, including that it’s one of the best cities for walking. While he makes the valid point that LA’s beautiful weather gives it an advantage over many other American cities with good walking opportunities, I have to disagree that it ranks among the best cities for walking as a tourist or for enjoyment. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this topic because my boyfriend is from LA and has often tried to convince me that it has great walking neighborhoods. Tyler is clearly correct that weather is an important aspect of walkability, so whether or not LA can compete with older, colder American cities on walkability depends on the walker’s preferences for weather relative to other factors like aesthetics and safety. Personally, I weight urban design much more heavily for walkability than weather, and from this standpoint I don’t think LA can compete with the few cities built before wide boulevards became standard street construction. As Nathan Lewis points out, American city planners began building wide streets well before personal cars became common for transportation. Only the U.S.’s oldest neighborhoods that predate the Revolutionary War feature the narrow streets that facilitate a pedestrian scale environment. Stephen Stofka at Strong Towns supports 1:1 as the best ratio of building height to street width, but personally, I prefer a “really narrow street” design with mid-rise buildings, with a ratio often approaching 2:1. With buildings taller than the streets, pedestrians feel a sense of enclosure and close-in building facades pull the walker along as compared to the expansiveness of wide streets that make comparable walking distances feel farther. Although some call Boston’s financial district an urban canyon, to me it’s one of the most interesting places to walk that I’ve […]

Last week DC Streetsblog reported on a new survey from Kaiser Permanente. The survey covers Americans’ attitudes toward walking and their self-reported walking habits. While a substantial majority of people believe that walking has health benefits ranging from weight management to alleviating depression, the survey found that most people walk less than the 150 minutes per week that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends. The Streetsblog coverage attributes a lack of walkable infrastructure to low walking rates, although it’s not clear to me that the survey explicitly supports this conclusion. However, past research demonstrates that people who live in neighborhoods where they are able to complete errands on foot do, unsurprisingly, do walk more than those who don’t. While people may not cite walkabilty as an important consideration in choosing a house, choosing a home involves weighing many factors, from size, price, distance to work and other amenities, aesthetic, and countless others factors. Consumers rely on tacit knowledge to weigh many of these factors because they can’t consciously enumerate all of them in making a decision of where to live. For this reason, revealed preference theory is a more reliable tool than survey data for observing how consumers value one attribute of a complex good like housing. Building on a past project, my colleague Eli Dourado and I are studying whether or not consumers do pay a premium for greater neighborhood walkability. Using a fixed-effects model, across all metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas in the United States, our preliminary results indicate that, on average, Americans are willing to pay a premium of about $850 for a house with one additional point in Walk Score. Because of the many restrictions that limit walkable development, consumers have to pay this premium for the scarce supply of houses in walkable neighborhoods. This finding […]