Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In his new book The Human City, Joel Kotkin tries to use NIMBYism as an argument against urbanism. He cites numerous examples of NIMBYism in wealthy city neighborhoods, and suggests that these examples rebut “the largely unsupported notion that ever more people want to move ‘back to the city’.” This argument is nonsense for two reasons. First, the NIMBYs themselves clearly want city life and a certain level of density–otherwise they would have moved to suburbia. In cities like Los Angeles and New York, a wide range of housing choices exist for those who can afford them. Second, the fact that some people want to prohibit new housing does not show that there is no demand for new housing. To draw an analogy: the War on Drugs prohibits many drugs. Does that mean that there is no demand for drugs? Of course not. If anything, it proves that there is lots of demand for drugs; otherwise government would not bother to prohibit it. For my more in-depth review of The Human City, read: Joel Kotkin’s New Book Lays Out His Sprawling Vision For America

If you regularly read about cities, you might notice that Texas cities rarely seem to come up. We make cases for why Detroit is definitely coming back—just you wait! We come up with elaborate theories of how cities can become the next Silicon Valley. We spend hours coming up with a solution to New York City’s costumed panhandler problem. Yet the four urban behemoths of the Lone Star State—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin—remain conspicuously absent from the conversation. Boy, has that changed. Earlier this year I wrote a sprawling defense of Houston. Scott Beyer spent the summer writing a series of articles for Forbes profiling the cool things happening in cities across the state. John Ricco recently launched the “Densifying Houston” Twitter feed and discussed the phenomenon on Greater Greater Washington. Just this past weekend, City Journal released an entire special issue dedicated to Texas. Through all this, many have been surprised to learn that a city like Houston could serve as a model for land-use policy and economic growth for struggling coastal cities. Yet two criticisms regularly seem to come up, at least related to Houston: “Houston is an unplanned hell-hole! It’s proof that land-use liberalization would be a disaster.” “Houston isn’t unplanned! It’s as heavily planned as any other city, just look at the covenants.” Since there seems to be a lot of confusion about land-use regulation and planning in Houston, here’s a quick explainer on what Houston does regulate, doesn’t regulate, and how private covenants shape the city. 1. What Houston Doesn’t Do Houston doesn’t mandate single-use zoning. Unlike every other major U.S. city, Houston doesn’t mandate the separation of residential, commercial, and industrial developments. This means that restaurants, homes, warehouses, and offices are free to mix as the market allows. As many have pointed out, however, market-driven separation of incompatible uses—think […]

One common argument against Airbnb and other home-sharing companies is that they reduce housing supply by taking housing units off the long-term market.* As I have written elsewhere, I don’t think home-sharing affects housing supply enough to matter. But even leaving aside the empirical question of whether this will always be true, there’s a theoretical problem with the argument that if someone fails to use their land for long-term rental housing, government must step in. It seems to me that this argument, if applied with even a minimal degree of consistency, leads to absurd results. For example, suppose that Grandma has a spare room in her house, and instead of renting it on Airbnb she allows the room to be unused. Should Grandma be forced to rent out the room? Of course not. A home-sharing critic might argue that an unused room is different from a room that is likely to be rented out to a long-term tenant. Indeed it is- but in fact, Grandma’s failure to rent the room to anyone is more socially harmful than her renting the room on Airbnb. In the latter situation, a traveler benefits (from a cheaper rate than a hotel, or at least for a different kind of experience) and Grandma benefits by getting money from the traveler. By contrast, in the former situation, no one benefits. It could be argued that Grandma’s rights should be unimpeded, but that regulation should be targeted towards the amateur hotelier who seeks to rent out an entire building all-year round, rather than using the building for more traditional tenants. Even here, the argument based on housing scarcity leads to absurd results. Suppose the evil landlord Snidely Whiplash decides, instead of renting out his building on Airbnb, to use the building for a vacation house one day a year […]

Yet another study in a long line of others provides evidence that land-use regulations restrict housing supply. A new paper identifies a correlation between land-use regulations in California cities and the growth rate for housing units. Kip Jackson finds that California zoning rules and other land-use restrictions not only reduce the growth rate of new housing stock, but a new regulation can actually be expected to reduce the existing stock of housing by 0.2% per year. This correlation is greatest when looking only at multifamily buildings, where each new restriction results in 6% fewer apartments built annually. Kip uses panel data on California land-use regulations from 1970-1995. Researchers sent surveys to municipal planning departments to create a dataset including both the regulations in effect in each city and the year they were enacted. The panel dataset allows Kip to use two-way fixed effects. That means that his results control both for factors that affect housing growth in all cities at a given time and for factors that affect growth in a specific city over time. This survey data makes it possible to study both the effects of the total quantity of rules along with the effects of specific rules. Kip finds that rules that are likely to make it more difficult to build in the future lead to an increase in building permits at the time they are implemented. For example, urban growth boundaries and rules that require a supermajority council vote to approve increased residential density spur current year housing permits. This increase is likely due to developers’ belief that building permits will become more difficult to obtain the longer the new regulation is in effect. He points out that some studies that fail to find a relationship between zoning and housing supply may find this null result because of rules that change the timing of development while reducing it over the […]

Last week, Reason.tv (the multimedia outlet of Reason Magazine) published a video about San Francisco’s YIMBY movement. The video describes the decades of underdevelopment in San Francisco as the result of community activism intended to limit the supply of new construction. As a result, San Francisco’s housing market is severely supply-constrained, and outrageously expensive. The problem has gotten so bad that pro-development, “YIMBY” organizations such as SFBARF and Grow San Francisco have sprung up to counter the anti-development forces. It’s great to see Reason taking notice of the YIMBY movement, and we’d love to see more attention paid to urbanism at libertarian sites. Three of us at Market Urbanism attended the first nationwide YIMBY conference in Boulder that the video mentions, and we’ll be sharing our thoughts on the conference soon. (h/t Jake Thomas at the Market Urbanism facebook group)

Inclusionary Zoning is an Oxymoron The term “Inclusionary Zoning” gives a nod to the fact that zoning is inherently exclusionary, but pretends to be somehow different. Given that, by definition, zoning is exclusionary, Inclusionary Zoning completely within the exclusionary paradigm is synonymous with Inclusionary Exclusion. What is Inclusionary Zoning? “Inclusionary Zoning” is a policy requiring a certain percentage of units in new developments to be affordable to certain income groups. Sometimes, this includes a slight loosening of restrictions on the overall scale of the development, but rarely enough loosening to overcome the burden of subsidizing units. Many cities, particularly the most expensive ones, have adopted Inclusionary Zoning as a strategy intended to improve housing affordability. Often, demand for below-market units are so high, one must literally win a lottery to obtain a developer-subsidized unit. Economics of Exclusion We must first acknowledge the purpose of zoning is to EXCLUDE certain people and/or businesses from an area. Zoning does this by limiting how buildings are used within a district, as well as limiting the scale of buildings . These restriction cap the supply of built real estate space in an area. As we know from microeconomics, when rising demand runs into this artificially created upward limit on supply, prices rise to make up the difference. As every district in a region competes to be more exclusive than its neighbors through the abuse of zoning, regional prices rise in the aggregate. Since the invention of the automobile, and subsequent government overspending on highways, sprawl has served as the relief valve. We’ve built out instead of up for the last several decades and this sprawl has relieved some of the pressure major metropolitan areas would have otherwise felt. In fact, it’s worked so well–and led to the abuse of zoning rules for such a long time–that exclusionary zoning has become the accepted paradigm. Zoning is the default flavor of […]

Emily Washington recently wrote for Market Urbanism about the need for low quality housing, attributing some of the high cost of housing in U.S. cities to building codes that increase construction costs. Some provisions of building codes were encouraged by social reformers and reflect middle-class standards and expectations, rather than necessities of health and safety. Over at Rooflines, Jamaal Green responds that there is no shortage of low quality housing in the U.S. Anyone with a cursory familiarity with the lower end of the U.S. housing market can vouch for the fact that there are many dwellings out there, in cheap cities and expensive ones alike, that are very low quality in their ability to provide shelter, keep out pests, supply functioning water and sewer connections, and so on. Part of the issue here is that quality can be used to convey a wide variety of characteristics. Something can be low quality in the sense that it is hazardous to human health and safety, or something can be low quality in the sense that, while functional, it doesn’t meet the aesthetic preferences of the neighbors. As Paul Groth details in Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States, it is clear that many zoning and building code provisions reflect the middle-class sensibilities of Progressive Era reformers. In particular, living arrangements that were not centered on family life, such as residential hotels and rooming houses, were nearly driven out of existence. Unlike the lower end single-room cubicles of Groth and the doss houses of Jacob Riis, this was not due to public health, but to the perceived impact on social relations of residents. Turn of the century hotels and rooming houses made it possible for women to live alone and for both men and women to engage in intimate relationships, straight […]

The Austin area has, for the 5th year running, been among America’s two fastest-growing major metro areas by population. Although everybody knows about the new apartments sprouting along transportation corridors like South Lamar and Burnet, much of the growth has been in our suburbs, and in suburban-style areas of the city. Our city is growing out more than up. How come? The desire for living in central Austin has never been higher. But Austin, like most cities, has rules that prevent new housing from getting centrally built. That makes it easier to buy and build on virgin land in the suburbs. Here are some of those rules. 1 MINIMUM LOT SIZE Historically, expensive houses were built on expensive, large lots; cheaper homes were built on smaller, cheaper lots. Austin decided that new houses can’t be built on small lots. Even if you want to build a small, cheap house, you still need a lot with at least 5,750 square feet. In central Austin, that costs a lot of money, even without the house! If somebody owns a 10,000 square foot lot, they aren’t allowed to split it into two 5,000 square foot lots and build two medium-sized houses, let alone three 3,333 square foot lots with three small houses, let alone three 3,333 square foot lots with triplexes! In 1999, Houston reformed its minimum lot size laws. Since then, environmentally-friendly central-city urban townhomes have flourished. 2 MINIMUM SITE AREA For areas that are zoned for apartments and condos, there is a cap on the ratio of number of apartments to lot size known as “minimum site area.” 3 IMPERVIOUS COVER MAXIMUMS Impervious cover is any surface that prevents water from seeping into the ground, including buildings, driveways, and garages. There is a cap on the ratio of impervious cover to lot size. 4 FLOOR-TO-AREA RATIO MAXIMUMS Floor-to-area ratios (aka FAR) maximums are a cap on […]

When it comes to the impact autonomous cars will have on cities, there’s plenty of room for disagreement. Will they increase or decrease urban densities? Will they help with congestion or make it worse? At the same time, there seems to be widespread agreement on at least two things: First, far fewer people will own cars. Second, we are not going to need nearly as much parking. By combining the technology of autonomous cars with the business model of transportation network companies like Uber and Lyft, low-cost, on-demand ride-hailing and dynamic routing bus lines could eliminate the need to keep an unused car hanging around for most of the day. When that happens, we will need far fewer parking spaces, turning on-street parking into wider sidewalks and bike lanes and surface lots and parking ramps into residential and commercial uses. So how does the humble American residential garage fit into all this? On its face, the garage is little more than the sheltered parking space that comes with most single-family homes. Yet the garage holds a certain mythological status in the American psyche: It gave rise to iconic American brands like Disney, Harley Davidson, and Mattel. It offered a space in which the firms that would launch the digital economy could get their start, including HP and Apple. Google and Microsoft, which both started in garages, maintain “garage” work spaces to this day in order to cultivate innovation. By providing a flexible space in which knowledge, free time, and ambition can transform into entrepreneurial innovation, the garage has played a crucial role in the American economy. At least in the near term, garages are not going anywhere. Unlike municipal governments and large private landowners who will likely face immediate political and market pressures to retool their parking spaces, many homeowners are structurally stuck with their garages. Millions of garages could go unused, occasionally kept active by automobile hobbyists, most likely turning into de facto storage units. But it doesn’t have to be […]

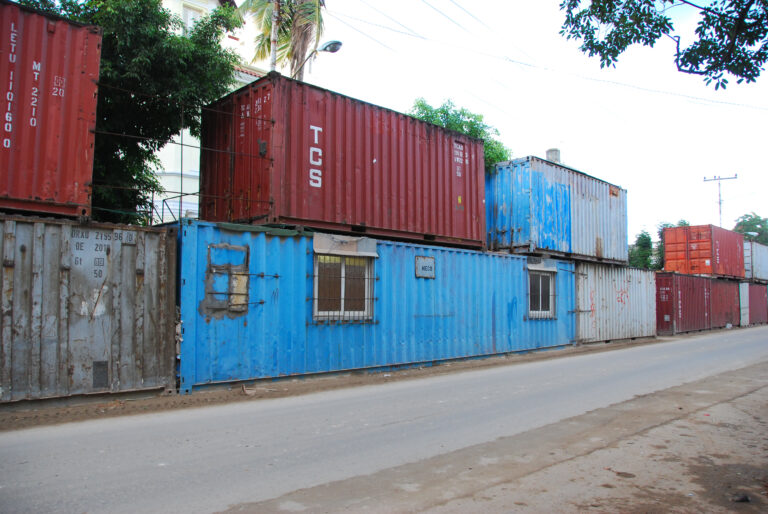

Washington, D.C. has a monopoly on many things. Bad policy, unfortunately, isn’t among them. Last month, a development corporation in Lexington, Kentucky installed a shipping container house in an economically distressed area of town to improve housing affordability. The corporation is a private non-profit, though a line near the end of this article indicates that the project received public support: “The project is funded through an assortment of grants from the city’s affordable housing fund [and two philanthropic organizations].” Shipping container projects designed to improve housing affordability aren’t limited to my Old Kentucky Home: a quick Google search reveals that the idea of using shipping containers to put a dent in housing costs is popular among policymakers and philanthropists all over the world. The sad reality is that shipping container homes likely have little—if any—role to play in handling the nationwide housing affordability problem. Aside from being inefficient for housing generally, there’s decent evidence that shipping containers appeal far more to reasonably well-off, single urbanites than to working families in need of affordable housing. More broadly, the belief that these projects could address the growing affordability crisis hints at a profound misunderstanding of the nature of the problem and distracts policymakers from viable solutions. Before digging into the meatier problems, it’s worth looking first at the problems with the structures themselves. I’ll yield to an architect: Housing is usually not a technology problem. All parts of the world have vernacular housing, and it usually works quite well for the local climate. There are certainly places with material shortages, or situations where factory built housing might be appropriate—especially when an area is recovering from a disaster. In this case prefab buildings would make sense—but doing them in containers does not. The source goes on to detail the enormous costs associated with zoning approval, insulation, and utilities. Then there’s the somewhat obvious fact that they’re small. As in, 144 square […]