Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Washington, D.C. has a monopoly on many things. Bad policy, unfortunately, isn’t among them. Last month, a development corporation in Lexington, Kentucky installed a shipping container house in an economically distressed area of town to improve housing affordability. The corporation is a private non-profit, though a line near the end of this article indicates that the project received public support: “The project is funded through an assortment of grants from the city’s affordable housing fund [and two philanthropic organizations].” Shipping container projects designed to improve housing affordability aren’t limited to my Old Kentucky Home: a quick Google search reveals that the idea of using shipping containers to put a dent in housing costs is popular among policymakers and philanthropists all over the world.

The sad reality is that shipping container homes likely have little—if any—role to play in handling the nationwide housing affordability problem. Aside from being inefficient for housing generally, there’s decent evidence that shipping containers appeal far more to reasonably well-off, single urbanites than to working families in need of affordable housing. More broadly, the belief that these projects could address the growing affordability crisis hints at a profound misunderstanding of the nature of the problem and distracts policymakers from viable solutions.

Before digging into the meatier problems, it’s worth looking first at the problems with the structures themselves. I’ll yield to an architect:

Housing is usually not a technology problem. All parts of the world have vernacular housing, and it usually works quite well for the local climate. There are certainly places with material shortages, or situations where factory built housing might be appropriate—especially when an area is recovering from a disaster. In this case prefab buildings would make sense—but doing them in containers does not.

The source goes on to detail the enormous costs associated with zoning approval, insulation, and utilities. Then there’s the somewhat obvious fact that they’re small. As in, 144 square feet small, or a little over one seventh the size of the average American apartment. That’s without insulation, which shaves off valuable feet. One could argue that American homes should be smaller, but as we should have learned by now, public housing projects are no place for social experiments. Working-class families are already the victims of public policies that undermine housing affordability. There’s no need to salt the wound by publicly supporting housing they have no interest in inhabiting.

The uncomfortable fact is that these homes may not even be made for working-class residents. While data on shipping container residents is limited, tiny house demographic data serves as a helpful proxy. According to data from a popular tiny houses website (take it with a grain of salt), tiny house residents have a per capita income of $42,038, putting them just over $10,000 above the typical Fayette County (home to Lexington) resident. Residents are also twice as likely as the general public to have a master’s degree. Who are these people with high human capital and average wages? We might follow the urban theorist Richard Florida and call them “bohemians.” Consider this quote from the initial piece:

A single person may make up to $38,200 a year to qualify for the program. A family of four may make up to $54,550.

Set aside for a moment the horrifying mental image of a family of four living in a 144 square foot shipping container. Who is this “single person” earning up to $38,200 who might want to live in an experimental home? To be frank, it sounds like the typical recent college graduate: individuals with modest incomes, liberal lifestyle preferences, and little need for space. While one might reasonably be on the fence about natural gentrification in cities, policymakers and philanthropists should be careful not to needlessly displace those they’re trying to help.

Shipping container houses are in all likelihood a poor fit for working-class Americans, and widespread government support for them in low-income communities runs the risk of rapid, unnatural gentrification. Worse still, treating the emerging shipping container house movement as a housing affordability fix distracts us from the true cause of “too-damn-high” rent: restrictions on the supply of housing.

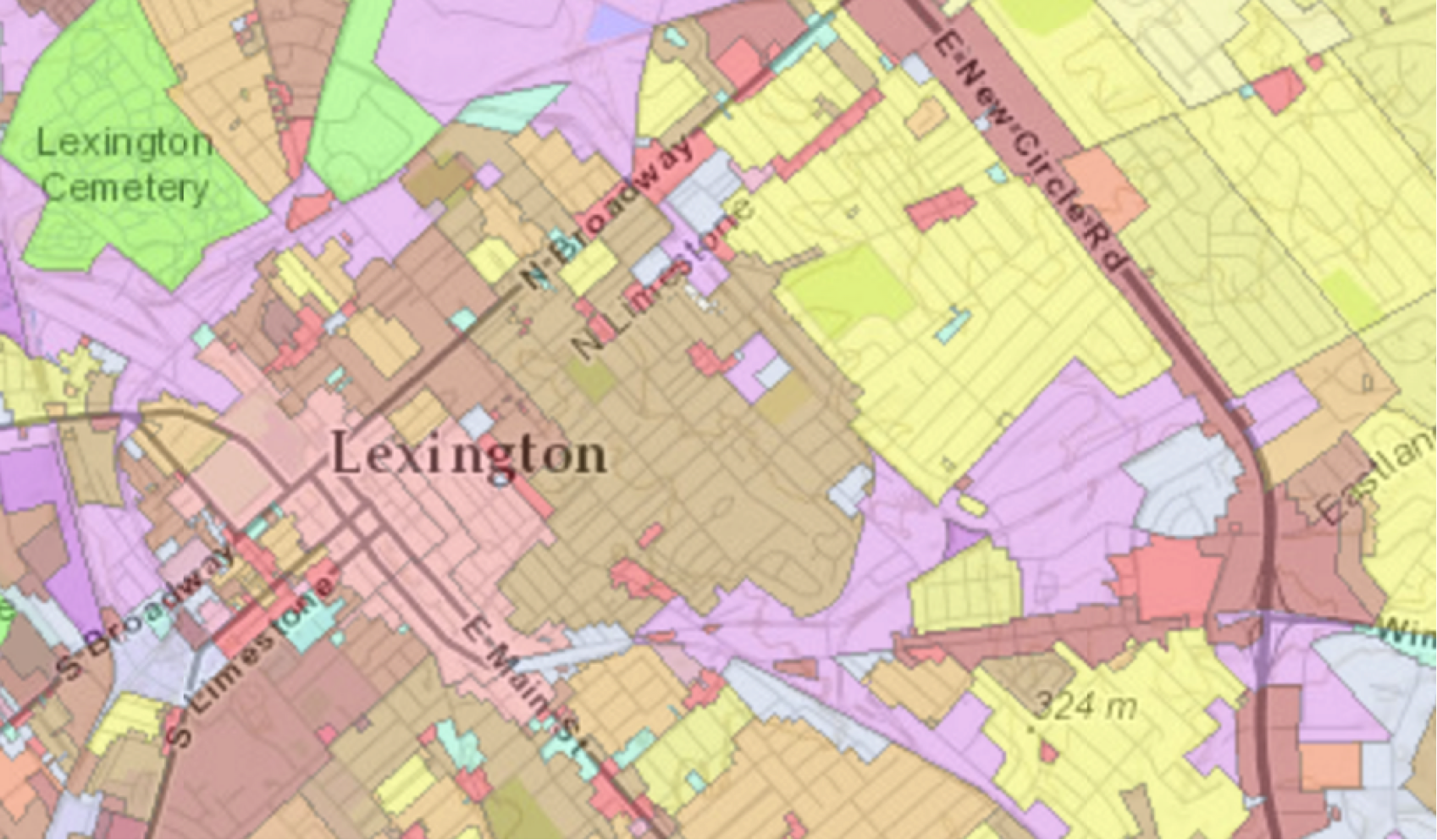

The problem of rising housing costs is, at its heart, a supply and demand problem. In a working housing market, developers and non-profits are able to meet unmet demand through new construction. Yet in many American cities, including Lexington, the ability to build new houses and apartments is strictly limited. Policies as diverse as minimum lot sizes, mandatory parking minimums, urban growth boundaries, and inclusionary zoning all serve to arbitrarily limit the supply of housing, driving up rents and house prices as demand increases. Though zoned for multi-family housing, the area in question—northern Lexington—is subject to a variety of regulations that needlessly restrict supply, including mandated parking requirements, a three-story height limit, and density-reducing use restrictions. Worse still, this is comparatively liberal zoning in a town mostly zoned for single-family houses and agriculture. It may be politically difficult, but the policy fix for improving housing affordability is clear: eliminate regulations that needlessly restrict the housing supply.

When it comes to ensuring housing affordability, the focus must remain on building a dynamic urban housing market in which working-class people have the choice to live wherever they like, whether that’s a shipping container or a house in the suburbs or an apartment downtown. This means reigning in land-use regulations that undermine new development. The fact that this project took a year to gain approval speaks to the problem. Lexington is a great city, and people are realizing it. If demand continues to increase while supply remains restricted, housing affordability will only get worse. A few shipping container houses may look cool, but they won’t sustainably address the problem.

Follow me on Twitter at @mnolangray.

CDCs do a variety of different housing developments for a variety of different target households. There is nothing to suggest that the Lexington affordable housing community has declared shipping containers to be the one and only solution to meeting housing need.

Inaccurate information just weakens your argument. So, to clarify a few points—The container home being built is a 640SF, 1BR/1bath–not a 144 SF unit intended for a family of four. It’s not unusual for it to take a year or longer for a development to go from idea to groundbreaking. That’s how long it takes to put together financing, architectural drawings, construction documents, etc.

Housing advocates really need to have a basic understanding of the development process in order to be more effective. This article gives a few more details on the project.

http://www.kentucky.com/news/local/counties/fayette-county/article53353755.html

Thanks for the feedback. A few quick comments:

1. It’s good that CDCs try out different methods of addressing social issues. The CDC mentioned in this article is doing great work in other areas. But for a project with such dubious benefits to the community, the case for public funding is extremely weak.

2. Ah, couldn’t find information on the square footage for this particular project online. It’s not uncommon for shipping container projects to plan for 144 SF units. Back to this case, 640 SF is certainly more reasonable than 144 SF, though still a hair above half the size of a typical home in this neighborhood. Even at 640 SF the project is still smaller than your typical singlewide trailer and far more expensive. This ties back to my broader skepticism that this project was actually designed for low-income residents. Again, fine for private funding to support such projects but probably not a good fit for public funds set aside for housing affordability issues.

I haven’t seen anyone living in just one container. I have seen 6 stacked up double wide and 3 high and others laid out in groups of 4 to 8 and joined together..