Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

This month marks the 100th anniversary of two pieces of legislation that revolutionized the way we live. On July 11, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the first Federal Aid Road Bill. And on July 25, 1916–exactly 100 years ago today–New York City passed the country’s first comprehensive zoning ordinance. Prior to 1916, transportation infrastructure was primarily a local and/or private responsibility. For example, cities leased their rights-of-way to trolley companies, which operated transit lines. Railroad companies provided travel service between cities. The 1916 Federal Road Bill was the first step in nationalizing transportation infrastructure funding, with the state highway departments formed to manage federal appropriations for roads. These two pieces of legislation produced radical change, as government favoritism of automotive infrastructure crowded out other transportation modes and undermined innovation. In the century prior to 1916, entrepreneurs invented steam ferries, trains, bicycles, trolleys, and automobiles. Such advances ceased after 1916. Yes, today’s cars are more comfortable and powerful, but they have the same steering wheel, four tires, and internal combustion engine as the Model-T Henry Ford was building 100 years ago. As for roads, the main difference is they are bigger. Unable to compete with government favored automobiles, Charleston’s last private ferry operator closed shop in 1930. Its trolley lines, which carried 20 million passengers/year (compared with CARTA’s 5 million/year) stopped running in 1937. Zoning is segregation – not only of land uses deemed incompatible, but of people deemed “undesirable.” Progressives behind New York City’s 1916 zoning ordinance regarded immigrants moving into northern cities from Europe and the South as “undesirable.” In 1921, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover tapped Edward Bassett, the leading advocate of New York City’s 1916 zoning, to create a model zoning ordinance. Engineer Morris Knowles also served on this committee. In its 1926 landmark decision in Euclid v. […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Quantifying the effects of California zoning rules by Emily Hamilton Kip Jackson finds that California zoning rules and other land-use restrictions not only reduce the growth rate of new housing stock, but a new regulation can actually be expected to reduce the existing stock of housing by 0.2% per year. This correlation is greatest when looking only at multifamily buildings, where each new restriction results in 6% fewer apartments built annually. Tech for Housing: An Experiment in YIMBY Activism by Jeff Fong We want to make participation in land use reform a conspicuously consumable good within Bay Area tech. We want everyone within tech to identify as YIMBY by default and for that reflexive self-identification to tip the scales of everyone’s internal cost benefit analysis in favor of having an articulable opinion and taking minimal actions like sending a letter, signing a petition, or casting a vote. 2. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Shanu Athiparambath wrote, Elevators are a Mass Transit System Adam Millsap wrote, Recessions Don’t Have The Same Impact On Every City Shanu Athiparambath wrote, Zoning Is Unjust, Anti-Poor & A Cause of Inequality via Tobias Cassandra Holbrook: Cash-Strapped Towns Are Un-Paving Roads They Can’t Afford to Fix via Vinay Natu, “Man behind charter cities – Paul Romer, named for Chief Economist, World Bank“ via Melanie Meharchand, “The Coastal Commission wrote a letter chiding the City of Laguna Beach for its overly-restrictive regulations on short-term rentals.” via Nolan Gray, “Hard to tell who’s more irritating here, the weirdo utopian schemers or the petty narrow-minded NIMBYs:” A Mormon Tycoon Wants to Build Joseph Smith’s Mega-Utopia in Vermont via Roger Valdez: Renting in Seattle? City could put a cap on your move-in fees via Matt Robare: The Tyranny of Free Parking via Jake Thomas: Housing […]

Tech for Housing was founded to organize Bay Area tech workers around supply friendly land use reform. Tony Albert, Joey Hiller and myself, all saw an unmet need for tech-centric political outreach and decided to try our luck. And as tech workers ourselves, we had certain ideas around the best ways to self-organize and why that organization hadn’t really happened to date. One problem with mobilizing Bay Area tech, we realized, is that many of us spend 50-60 hours a week at work. For those of us that weren’t already passionate about land use issues (yes, I’m aware I just used the terms ‘passionate’ and ‘land use’ in the same sentence), spending significant time and energy to understand, let alone act on, reform is asking a lot. We also noted that tech workers are, to varying degrees, transplants. Consequently, the existing political infrastructure that’s not too great at mobilizing tech workers generally is even less effective at activating recent arrivals who might not even be registered to vote in their new jurisdiction. After thinking through these and other reasons that we in tech remain politically apathetic, we realized the challenge was to dramatically increase the perceived benefit and decrease the perceived cost of political participation. To that end, we’ve started with tech focused content on housing policy, explaining at a high level 1) what’s broken, 2) why it’s broken and 3) what can be done about it. A lot of what’s happening at this stage is attracting the other workers in our industry who are already wonky enough to have read How Burrowing Owls Lead to Vomiting Anarchists two or three times. And after developing that core audience, providing them ways to activate our less engaged colleagues via various forms of social signaling. There’ll only ever be a certain number of people […]

Yet another study in a long line of others provides evidence that land-use regulations restrict housing supply. A new paper identifies a correlation between land-use regulations in California cities and the growth rate for housing units. Kip Jackson finds that California zoning rules and other land-use restrictions not only reduce the growth rate of new housing stock, but a new regulation can actually be expected to reduce the existing stock of housing by 0.2% per year. This correlation is greatest when looking only at multifamily buildings, where each new restriction results in 6% fewer apartments built annually. Kip uses panel data on California land-use regulations from 1970-1995. Researchers sent surveys to municipal planning departments to create a dataset including both the regulations in effect in each city and the year they were enacted. The panel dataset allows Kip to use two-way fixed effects. That means that his results control both for factors that affect housing growth in all cities at a given time and for factors that affect growth in a specific city over time. This survey data makes it possible to study both the effects of the total quantity of rules along with the effects of specific rules. Kip finds that rules that are likely to make it more difficult to build in the future lead to an increase in building permits at the time they are implemented. For example, urban growth boundaries and rules that require a supermajority council vote to approve increased residential density spur current year housing permits. This increase is likely due to developers’ belief that building permits will become more difficult to obtain the longer the new regulation is in effect. He points out that some studies that fail to find a relationship between zoning and housing supply may find this null result because of rules that change the timing of development while reducing it over the […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Nick Zaiac contributed his first Market Urbanism piece: The Cato Institute Goes After Arbitrary Historic Preservation Laws between municipalities they can vary, depending on the precedents set by different circuit courts. Now the Cato Institute, a libertarian Washington think tank, is filing a brief that aims to bring consistency to these laws nationwide. Your Town Is A Financial Timebomb by Johnny Sanphilippo: Do your best Ross Perot imitation and say the words, “sucking sound.” The primary difference between the older development pattern and the stuff that’s being built today has to do with the ratio of public investment vs. private value. Downtown and the adjacent residential areas are mostly small-scale, compact, multi-story buildings with a minimum amount of roads, pipes, and wires connecting them. The new stuff is overwhelmingly huge roads, attenuated water and sewer lines, endless cables and a tremendous amount of surface parking and grass. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent his first week in Austin, and this weekend will visit the city’s northern suburbs, including Cedar Park, Round Rock and Georgetown. His Forbes article this week was about how Miami’s Parking Deregulation Will Reduce Housing Costs While Frey was unsure yet about what kind of rents the building would command, he estimated that building structured parking–in this case 12 spaces, under the previous regulations–would have cost $300,000, or $25,000 per space. This, he said, would have added roughly $330 per month to average rents 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Sandy Ikeda spoke about Jane Jacob’s legacy at the Museum of Eldridge Street alongside Mindy Fullilove and Ron Schiffman. Sandy asked the MU group for some clarification on statements made at the event by Ron Schiffman, an urban affairs scholar at the Pratt Institute. After some interesting dialogue, Sandy concludes Schiffman likely misused terms. David […]

I keep up with the reports and journalists proclaiming that America’s suburbs are thriving and will continue to do so forever. Yet I keep scratching my head since these depictions are in conflict with what I keep seeing on the ground as I travel around the country. The folks who declare the permanent triumph of suburbia must live in the prosperous enclaves near the lake and golf course, not the poorly aging subdivisions that are rapidly losing value and becoming reservoirs for the downwardly mobile former middle class. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with any of these homes, but here they are boarded up as the entire neighborhood slowly slides into decline. If the 1950’s subdivisions are looking dogeared you should check out the older neighborhoods from the early twentieth century. They’ve been neglected even longer and the collective deferred maintenance shows. I checked the real estate listings in this Georgia town and many of these homes can be bought for as little as $20,000. The average price seems to be closer to $40,000 or $50,000. Here’s one of the problems. This town has enjoyed a suburban building boom for the last few decades. These new homes are part of one of the better new communities being built on the far edge of town. These are desirable places to live and people who can afford to move here do so. Homes here are offered for between $350,000 and $500,000. But this region has a steady population. The number of people in the area has been increasing very slowly even as the number of new homes and commercial buildings continues to ramp up at a heady pace. There’s a direct connection between the impoverishment of the empty homes in the older parts of town and these new developments way out on the […]

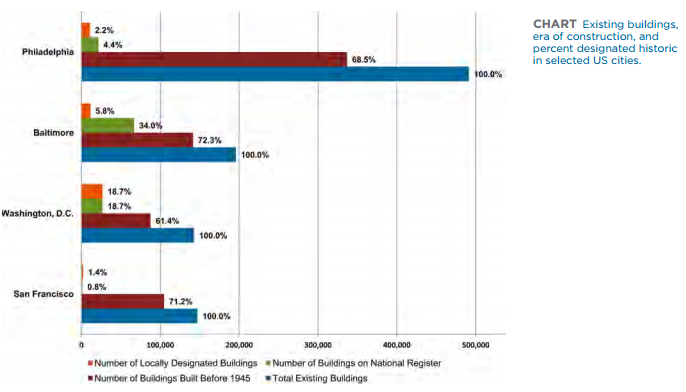

Historic preservation rules are part of the regulatory framework of most major American cities. But the historic districts in which they are generally applied get little inquiry from economists, meaning little is known about their nationwide scope and economic impact. And even between municipalities they can vary, depending on the precedents set by different circuit courts. Now the Cato Institute, a libertarian Washington think tank, is filing a brief that aims to bring consistency to these laws nationwide. In a 2014 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of urban economists led by Ed Glaeser found that historic districts in New York City experienced less construction, and affected where in the city developers build. More importantly, the economists found that preservation laws were costliest in neighborhoods where redevelopment would have been most valuable. Another paper, published in 2016 by NYU, to mark the 50th anniversary of New York City’s preservation laws, explored the relationships between historic districts and the type of buildings built, the type of buildings preserved, demographics of the residents in historic districts, and more. The evidence presented in both studies suggests that historic districts do indeed alter the human geography of cities. It validates William Fischel’s observation that “historic districts thus operate as another example of the double-veto system that state land use regulations add to municipal regulation except that in this case the potential veto arrives prior to municipal review rather than afterward” (Zoning Rules!, Page 62). In Nectow v City of Cambridge, the Supreme Court held that Massachusetts violated due process by “arbitrarily and unreasonabl[y]” imposing restrictions on certain land, in a way that did nothing to protect the public (which was the original rationale for land use regulations under the earlier Supreme Court case Euclid v Ambler). That said, the rules about which historic […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism, we’re Liberalizing Cities From The Bottom Up Middle Aged NIMBYs, Young YIMBYs by Michael Lewyn Most of the Pro-Urb posters on housing costs assume that high rents are the result of insatiable demand driven by wealthy foreigners, that government lets developers do as they please, and that housing supply is pretty much irrelevant. Why The Tech Industry Should Care About Housing by Jeff Fong Our broken housing system is silently depriving us of future contributors who could build great things; and for each individual who’s preemptively priced out, we’ll never know what those things might have been. Is Commercialism Making Cities Less Livable? by Shanu Athiparambath Are these people correct? If they were, the world’s most commercial cities would be the least livable. But anyone with a modicum of education or travel experience knows this is not true. The cities with the most economic freedom, commercial enterprise and prosperity–think Hong Kong, Singapore, London, Sydney and Vancouver–also have the highest living standards. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer will spend his last day in Dallas tomorrow visiting the downtown location of the recent sniper attacks. The rest of his weekend will be in Fort Worth, and the rest of July in Austin, stop #7 on his 30-city writing tour. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Brent Gaisford wants to get together with fellow Los Angelenos “if you want to get more involved in the fight for affordable, urbanist housing in LA“ Sandy Ikeda is surprised by an update on China‘s largest “ghost city” Cato Institute filed a brief urging the Supreme Court to take up a case that would restrict historical districting via takings law. Nick Zaiac and Randal John Meyer were involved in the research Shanu Athiparambath wrote Why Building In India Is A Challenge and These Income Segments […]

Commercialism is blamed for most of the evils that plague society, inside and out of India. In the Indian city of Coimbatore, roads have become narrower and traffic more intense. There is not enough space for pedestrians. Many residents blame the city’s rising level of commercialization. Are these people correct? If they were, the world’s most commercial cities would be the least livable. But anyone with a modicum of education or travel experience knows this is not true. The cities with the most economic freedom, commercial enterprise and prosperity–think Hong Kong, Singapore, London, Sydney and Vancouver–also have the highest living standards. Similar studies show that the cities with the lowest living standards, meanwhile, are in countries that are developing, or that are suffering under repressive, anti-capitalist regimes (think Caracas, Venezuela, the world’s most dangerous city). Nevertheless, it is clear that the most commercialized Indian cities have become less livable in some important ways, such as by suffering from more congestion. So, what is going on? It is true that people migrate to cities with more commercial enterprise. It may seem that such “crowding” is unpleasant. But people are migrating to these cities precisely because there are more shops, hospitals, schools, leisure spaces and other amenities. The fact that there is already a heavy concentration of people in these cities is an important factor also, since that means there are more potential employers and business associates. Alas, the existence of people somewhere lures yet more people. Indeed, it is hard to think of a neighborhood where real estate prices have significantly fallen because of population growth. Such neighborhoods may have become more crowded…but that does not mean they are less livable. Moreover, vast population growth and crowding are not the same. Population density is defined as the number of people living on […]

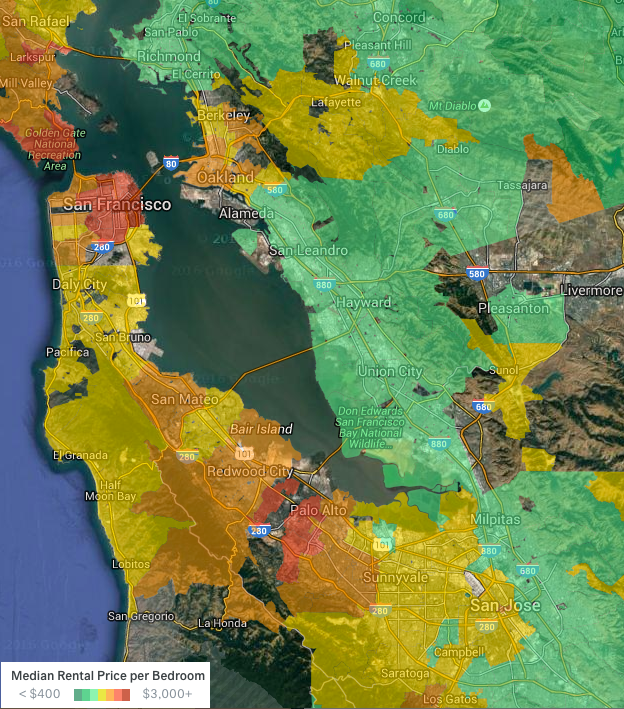

[Editor’s note–this is the inaugural article for a new blog that Jeff launched called Tech For Housing, where tech workers advocate for more housing in the Bay Area.] San Francisco–For decades, every city in the Bay Area has restricted housing production. And for decades, the Bay Area has gone deeper into housing debt. People and money continue streaming into the region, cities rarely allow new housing, and prices continue to rise. This hurts every industry in the Bay Area, and tech is no exception. The housing market steals money straight out of our pockets and, if we stay the current course, will rob us of the better version of ourselves we need more time to become. How Housing Robs Us Blind Housing in San Francisco costs 73% more than in Austin, 53% more than in Seattle, and 36% more than in Los Angeles. And figures for many of the Peninsula Cities are even worse. After accounting for cost of living, our real incomes in Bay Area tech are often lower than those of our colleagues in less expensive locales simply by virtue of housing costs. Obviously, this is bad for us as employees, but it hurts founders and investors as well. The higher housing prices climb, the more founders have to pay employees to provide for the same standard of living. And the higher labor costs become, the more money founders have to raise from investors, meaning more capital gets tied up funding the same amount of work. All this adds up to tech, as an industry, paying more and more to stay in the Bay Area for zero added benefit. Median Rental Price per Bedroom Source: Trulia But there’s more at stake than just burn rates and take-home pay. As it stands, housing prices are a millstone around our […]