Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

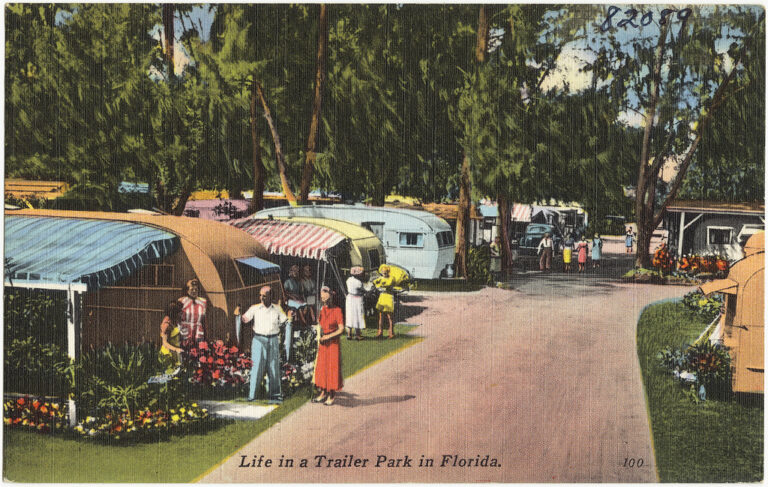

Given that “redneck” and “hillbilly” remain the last acceptable stereotypes among polite society, it isn’t surprising that the stereotypical urban home of poor, recently rural whites remains an object of scorn. The mere mention of a trailer park conjures images of criminals in wifebeaters, moldy mattresses thrown awry, and Confederate flags. As with most social phenomena, there is a much more interesting reality behind this crass cliché. Trailer parks remain one of the last forms of housing in US cities provided by the market explicitly for low-income residents. Better still, they offer a working example of traditional urban design elements and private governance. Any discussion of trailer parks should start with the fact that most forms of low-income housing have been criminalized in nearly every major US city. Beginning in the 1920s, urban policymakers and planners started banning what they deemed as low-quality housing, including boarding houses, residential hotels, and low-quality apartments. Meanwhile, on the outer edges of many cities, urban policymakers undertook a policy of “mass eviction and demolition” of low-quality housing. Policymakers established bans on suburban shantytowns and self-built housing. In knocking out the bottom rung of urbanization, this ended the natural “filtering up” of cities as they expanded outward, replaced as we now know by static subdivisions of middle-class, single-family houses. The Housing Act of 1937 formalized this war on “slums” at the federal level and by the 1960s much of the emergent low-income urbanism in and around many U.S. cities was eliminated. In light of the United States’ century-long war on low-income housing, it’s something of a miracle that trailer parks survive. With an aftermarket trailer, trailer payments and park rent combined average around the remarkably low rents of $300 to $500. Even the typical new manufactured home, with combined trailer payments and park rent, costs […]

Several cities have jumped on the bandwagon of building Micro-apartments, a hot trend in apartment development. San Francisco and Seattle already have them. New York outlawed them, but is testing them on one project, and may legalize them again. Even developers in smaller cities like Denver and Grand Rapids are taking a shot at micro-apartments. At the same time, Chicago is building lots of apartments, and is known for having low barriers to entry for downtown development. Yet we aren’t hearing of much new construction of micro-apartments here. Premier studios are fetching as much as $2,000 a month. Certainly there must be demand for something more approachable to young professionals. In theory, we should expect to see Chicago leading the way in innovative small spaces. Chicago doesn’t have an outright ban on small apartments like New York, but there are four regulatory obstacles in the Chicago zoning code. These are outdated remnants from eras where excluding undesirable people were main objectives of zoning, and combined to effectively prohibit small apartments: 1. Minimum Average Size: Interestingly, there is no explicit prohibition of small units. This is unlike New York City’s zoning, which prohibits units smaller than 400sf. There is, however, a stipulation that the average gross size of apartments constructed within a development be greater that 500sf. Assuming 15% of your floor-plate is taken by hallways, lobbies, stairs, etc; this means for every 300sf unit, you need one 550sf unit to balance it out. Source: 17-2-0312 for residential; 17-4-0408 for downtown 2. Limits on “Efficiency Units”: Zoning stipulates a minimum percentage of “efficiency units” within a development. The highest density areas downtown allow as much as 50%, but these are the most expensive areas where land is most expensive. In areas traditionally more affordable, the ratio is as low as 20% to discourage studios, and encourage […]

Hovering somewhere just beyond all the land use zoning regulations, building codes, finance mechanisms, aspirational comprehensive municipal plans, state mandates, and endless NIMBYism lies… reality. If you happen to want to live in certain parts of coastal California you need to come to grips with a serious supply and demand imbalance. Demand is endless. Supply is highly constrained. And there’s a huge amount of money on the table. Horizontal growth is essentially verboten. A powerful coalition of existing property owners, environmental groups, resource allocation schemes, and multi-tiered government regulations stymie new greenfield development. The personal interests of conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats line up exactly when anyone attempts to build anything near them. “Over my dead body.” It’s understood that if a town accepts endless low density horizontal development the overall quality of the area will decline. You can’t have expansive large scale suburbia without paving over the countryside, creating a great deal of traffic congestion, and inducing strip mall blight. At the same time, no one wants infill development on existing not-so-great property that’s already been paved over and degraded. The neighborhood associations break out the pitch forks and firebrands at the suggestion of multi-story condos or (Heaven forbid) apartment buildings. The population of any older suburb could double or triple without using a single inch of new greenfield land. But that kind of growth is feared and hated. So the aging muffler shops and parking lots linger in the middle of a massive housing crisis. Google Google Google On the other hand there’s radically less regulatory or community push back against expanding and improving existing suburban homes. Google Street View makes it possible to observe how a little post war tract home was transformed into a substantially larger residence. This kind of growth is entirely acceptable. The building […]

I have criticized the idea that the law of supply and demand no longer applies to big-city housing (or, as I call it, supply-and-demand denialism, or “SDD” for short). It just occurred to me that there are a few similarities between supply-and-demand denialists and those who deny climate change. To name a few: *Rejection of science. Climate change denialists reject climate science; SDD true believers reject economics. *Paranoid fantasies about foreigners. Some climate change denialists treat worldwide concern over climate change as a conspiracy by Europeans or Chinese to destroy the U.S. economy; SDD believers are obsessed with foreigners purchasing U.S. or Canadian real estate. *Obsessive fear of change. Climate change denialists assume that any possible limit on fossil fuel emissions will destroy the U.S. economy (despite the fact that we already have lots of taxes and regulations and somehow maintain a more-or-less First World standard of living). I suspect (though I realize this is conjecture) that SDD believers are often NIMBYs who fear, without any obvious basis in reality, that new housing will turn their neighborhood into a slum or into a playground for the rich. *Self-interest generating these fears. Climate change denialists get information from politicians funded by the fossil fuel industry (and media outlets that support those politicians), which has a strong interest in limiting regulation of fossil fuel pollution. NIMBYs are sometimes homeowners who have a financial interest in limiting new housing in order to keep prices and rents high, or housing activists who can more effectively argue for government-subsidized housing if housing prices are high.

One common argument against new housing in high-cost cities is that the rise of global capitalism makes demand for urban housing essentially unlimited: if new apartments in Manhattan or San Francisco are built, they will be taken over by foreign billionaires in quest of American real estate, who will use the apartments as banks rather than actually living in them or renting them out. It seems to me that this argument would be more likely to be true if a huge percentage of New York’s housing was used by foreign billionaires. But a recent article in Politico New York suggests otherwise. The article says that 89,000 New York apartments are owned by absentee owners (many of whom presumably rent them out). However, most of these apartments are not owned by Russian oligarchs or other global capitalists; for example, the co-op unit I rented a few years ago in Forest Hills (market value around $300K) was owned not by a foreign oligarch, but by the building’s former super. Presumably, the condos and houses likely to be owned by wealthy foreigners are the most expensive ones. So how many of these units were worth $5 million or more. Only 1554- a drop in the bucket in a city of 8 million people. And how many of the units were worth over $25 million? Only 445. So super-rich absentee owners are few and far between, and thus probably do not affect housing supply very much.

The Austin area has, for the 5th year running, been among America’s two fastest-growing major metro areas by population. Although everybody knows about the new apartments sprouting along transportation corridors like South Lamar and Burnet, much of the growth has been in our suburbs, and in suburban-style areas of the city. Our city is growing out more than up. How come? The desire for living in central Austin has never been higher. But Austin, like most cities, has rules that prevent new housing from getting centrally built. That makes it easier to buy and build on virgin land in the suburbs. Here are some of those rules. 1 MINIMUM LOT SIZE Historically, expensive houses were built on expensive, large lots; cheaper homes were built on smaller, cheaper lots. Austin decided that new houses can’t be built on small lots. Even if you want to build a small, cheap house, you still need a lot with at least 5,750 square feet. In central Austin, that costs a lot of money, even without the house! If somebody owns a 10,000 square foot lot, they aren’t allowed to split it into two 5,000 square foot lots and build two medium-sized houses, let alone three 3,333 square foot lots with three small houses, let alone three 3,333 square foot lots with triplexes! In 1999, Houston reformed its minimum lot size laws. Since then, environmentally-friendly central-city urban townhomes have flourished. 2 MINIMUM SITE AREA For areas that are zoned for apartments and condos, there is a cap on the ratio of number of apartments to lot size known as “minimum site area.” 3 IMPERVIOUS COVER MAXIMUMS Impervious cover is any surface that prevents water from seeping into the ground, including buildings, driveways, and garages. There is a cap on the ratio of impervious cover to lot size. 4 FLOOR-TO-AREA RATIO MAXIMUMS Floor-to-area ratios (aka FAR) maximums are a cap on […]

When laypeople hear the phrase “rent control”, they typically conjure up one of a few images. Tenants imagine easy street, a world where housing is ridiculously low cost. Maybe they think of rent control in NYC, where they saw the characters from Friends live in large apartments for far below market value. Landlords think of reduced profits, and tenants who live in a unit for years on end, never paying market value. Economists on both the left and right, meanwhile, simply picture bad policy. A prime example is Thomas Sowell, a world-renowned economist who claims both tenants and landlords suffer from rent control. He discusses the economics of rent control in his book Basic Economics, and his arguments have been summarized here. With Rent Control Comes a Greater Demand for Housing In an uncontrolled market, prices vary with the amount of demand. That is, prices rise because the amount of a product that people want exceeds the amount that is available at current prices. Put simply, more people want an item than there are items to go around, so to get that item you go into an indirect bidding process with other buyers. Imagine a fellow named Jerry and a girl named Elaine. Jerry wants a one-bedroom apartment in San Diego, but he can only afford $850 a month in rent. Elaine also wants to find a one-bedroom apartment, but she can afford $1,500 a month. Because there is currently a free market in San Diego, Jerry can’t find a one-bedroom for $850. There are a limited number of units and there are many more “Elaines” who are also willing to pay $1,500, which means rents hover around that value. As a result, Jerry reluctantly rents a 3-bedroom apartment with two roommates. Elaine finds a one-bedroom one at market price. […]

Browsing through peoples’ posts of their favorite things to do in Houston, there’s a recurring theme of eating out. USA Today called Houston “the dining-out capital of the nation”: on average, we eat out more often than any other city in the country, at the second-lowest average price (Zagat). The Chronicle claims Houstonians eat out a third more times per week at 20 percent lower cost than the national average, with 9,000 area restaurants to choose from (which also makes us one of the nation’s leaders in restaurants per capita). Finally, I’ve talked to tons of people who have moved away from Houston, and one of the first things they mention missing is the restaurants. So it’s definitely one of the great strengths of Houston, but also one that raises skepticism from anybody who hasn’t lived here: why would Houston have more or better restaurants than anywhere else? What’s so special about Houston? I think there are set of factors that have come together to create the “perfect storm” of great restaurants in Houston: Diversity. Start with Houston having a very diverse population from all over the globe, so there’s plenty of people available to start restaurants in their native ethnic cuisine. Not a whole lot of cities can say that. I think a lot of that is related to being the capital of the energy industry, which is an inherently global industry. That plus being a major port city and proximity to Latin America and Cajun Louisiana. Lack of zoning. Houston’s open development culture makes it easy for anybody to start a restaurant. Plenty of inexpensive space and not a lot of regulations/permitting. The freeway network. This may seem to be an odd factor, but think about it. We have a very well developed freeway network compared to […]

Last week I wrote a post highlighting how important it is for major cities to have places for low-income people to live. Without the opportunity to live in vibrant, growing cities, our nation’s poor can’t take advantage of the employment and educational opportunities cities offer. My post offended some people who don’t think that reforming quality standards is a necessary part of affordable housing policy. On Twitter @AlJavieera said that my suggestion that people should have the option to live in housing lacking basic amenities is “horribly conservative.” Multiple people said that my account of tenement housing was “ahistorical.” They didn’t elaborate on what they meant, but they seemed to think I was suggesting that tenements were pleasant places to live, or that people today would live in Victorian apartments if such homes were legalized. On the contrary, I argue that in their time, tenements provided a stepping stone for poor immigrants to improve their lives, and that stepping stone housing should be legal today. Historical trends provide evidence that people born into New York’s worst housing moved onto better jobs and housing over time. The Lower East Side tenements were first home to predominantly German and Irish immigrants, and later Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants. The waves of ethnicities that dominated these apartments indicate that the earlier immigrants were able to move out of this lowest rung of housing. The Tenement Museum provides multiple oral histories of people who were born into their apartment building and went on to live middle-class lives. In The Power Broker, Robert Caro provides an account of one community that had moved out of the Lower East Side to better housing in the Bronx: The people of East Tremont did not have much. Refugees or the children of refugees from the little shtetles in the Pale of Settlement and from the ghettos of Eastern Europe, the Jews who at […]

The market urbanism axiom — permitting housing supply to increase is key to achieving affordable housing — has been made recently by Rick Jacobus at Shelterforce and Daniel Hertz at City Observatory. However both argue that even with an increasing supply, low-income people will need aid in order to afford what the authors feel is adequate housing. History shows us, though, that if developers are allowed to serve renters in every price range, they will. The movie Brooklyn portrays the type of housing many of our grandparents and great-grandparents lived in when they emigrated to the United States. People of very little means could afford to live in cities with the highest housing demand because they lived in boarding houses, residential hotels, and low-quality apartments, most of which are illegal today. Making housing affordable again requires not only permitting construction of more new units, but also allowing existing housing to be used in ways that are illegal under today’s codes. Young adults living in group houses with several roommates have found a way around these regulations, but low-income renters were better-served when families and single people could pay for housing that was designed to meet their needs at an affordable price. Alan During explains the confluence of interest groups that successfully eliminated cheap, low-quality housing: The rules were not accidents. Real-estate owners eager to minimize risk and maximize property values worked to keep housing for poor people away from their investments. Sometimes they worked hand-in-glove with well-meaning reformers who were intent on ensuring decent housing for all. Decent housing, in practice, meant housing that not only provided physical safety and hygiene but also approximated what middle-class families expected. This coalition of the self-interested and the well-meaning effectively boxed in and shut down rooming houses, and it erected barriers to in-home boarding, too. Over more than a century, […]