Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Last year disappointed pro-housing advocates in Colorado, as Governor Polis’s flagship reform was defeated by the state legislature. But Polis and his legislative allies tried again this year, and yesterday the governor signed into law a package of reforms which cover much of the ground of last year’s ill-fated HB23-213. HB24-1152 is an ADU bill. It applies to cities with populations over 1000 within metropolitan planning areas (so, the Front Range – home to most of Colorado’s major cities – along with Grand Junction), and CDPs with populations over 10,000 within MPOs. Within those jurisdictions, the law requires the permitting of at least 1 ADU per lot in any zone that permits single-family homes, without public hearings, parking requirements, owner-occupancy requirements, or ‘restrictive’ design or dimensional standards. The law also appropriates funds available for ADU permit fee mitigation, to be made available to ADU-supportive jurisdictions which go beyond compliance with the law to make ADUs easier to build (including jurisdictions not subject to the law’s preemption provisions). HB24-1304 eliminates parking minimums for multifamily and mixed-use buildings near transit within MPOs (though localities can impose parking minimums up to 1 space per unit for buildings of 20+ units or for buildings with affordable housing, if they issue a fact-based finding showing negative impacts otherwise). This bill was pared down in the Senate and would originally have eliminated parking requirements within MPOs entirely. HB24-1313 is a TOD and planning obligations bill. The bill:– Designates certain localities as ‘transit-oriented’ (if they are within MPOs, have a population of 4,000+, and have 75+ acres total either within ¼ mile of a frequent transit route or within ½ mile of a transit station – in effect, 30 or so localities along the Front Range).– Assigns all transit-oriented communities (TOCs) housing opportunity goals, which are simply […]

How do urbanists respond to a disaster? Emails from Brazil's Rodrigo Rocha show innovation and personal resilience in the face of crisis.

Two law professors, Joshua Braver of Wisconsin and Ilya Somin of George Mason, are coming out with an article suggesting that exclusionary zoning (by which they mean, rules such as apartment bans and minimum lot sizes that are designed to exclude people less affluent than an area’s current residents) violate the Takings Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Rather than focusing solely on originalist interpretations of the clause and on policy-oriented “living Constitution” theories, the authors rely on both theories. Under a living Constitution view, they argue that zoning unfairly disfavors vulnerable minorities (anyone who cannot afford to live in a place under current zoning), unfairly limit individual autonomy by limiting the right to move to a new neighborhood, and creates an oligarchy of elite homeowners. From an originalist perspective, the authors argue that the Takings Clause was intended to protect “a right to use [property], not merely a right against physical seizure by the state.” The authors admit that this right is not absolute, but is limited by the police power of the state. However, the authors cite some early treatises suggesting that the police power is limited to truly dangerous activities, as opposed to merely unpopular land uses such as apartments.

Check out my new post at Metropolitan Abundance Project: How “inclusionary” are market-rate rentals? In metropolitan Baltimore, a family of four making $73,000 in 2024 qualifies for 60% AMI affordable housing, where it would pay $1,825 per month for rent, utilities included. A third of new market-rate three-bedroom units in Baltimore are rented at around that level.Baltimore is typical, as it turns out. In most U.S. metro areas, a substantial share of rentals constructed since 2010 were, in 2021 and 2022, affordable at 60% of AMI… You can also check out maps showing rentals affordable at 80% and 120% of AMI. The ACS data don’t let me distinguish market-rate from subsidized rentals, so these include LIHTC and other subsidized rentals. Those, however, can’t explain away the core result, and the data don’t show the bifurcated market that some people imagine, with a huge gap between market and deed-restricted rents.

Research shows that the implementation of an eviction moratorium significantly disadvantaged African Americans in the housing search process.

As anticipated by the “radical agreement” among the parties and justices at oral argument, the Supreme Court’s recently released decision in Sheetz v. County of El Dorado put to rest the question of whether legislatively-imposed land use permit conditions are outside the scope of the takings clause. The unanimous ruling confirms the common-sense proposition that a state action cannot evade constitutional scrutiny simply because it’s a law of general application rather than an administrative decree, and subjects conditions on building permits – whether monetary or not – to the essential nexus and rough proportionality requirements enshrined in the Nollan and Dolan cases. The narrow ruling reflects the sound principle that, when dealing with constitutional questions, a court shouldn’t address hypotheticals or other issues not in direct contention among the parties. Nonetheless, the majority felt compelled to state that it would not address “whether a permit condition imposed on a class of properties must be tailored with the same degree of specificity as a permit condition that targets a particular development,” which seems to leave open the possibility that the answer might be “no.” Justice Gorsuch, in his concurrence, was astonished by this statement, wondering how a court which had just endorsed the universal applicability of the takings clause could stumble into another arbitrary distinction with no basis in common sense or constitutional law. The court’s concern was not a jurisprudential one, but apparently a policy one: in another concurrence, Justices Kavanaugh, Kagan and Jackson note that “[i]mportantly, therefore, today’s decision does not address or prohibit the common government practice of imposing permit conditions, such as impact fees, on new developments . . . .” The justices’ impression that applying the current Nollan/Dolan formula to impact fees would or even could “prohibit” them is unfounded. As Emily Hamilton and I wrote […]

Just 1 in 25 new apartments is owner-occupied. What happened to building condos?

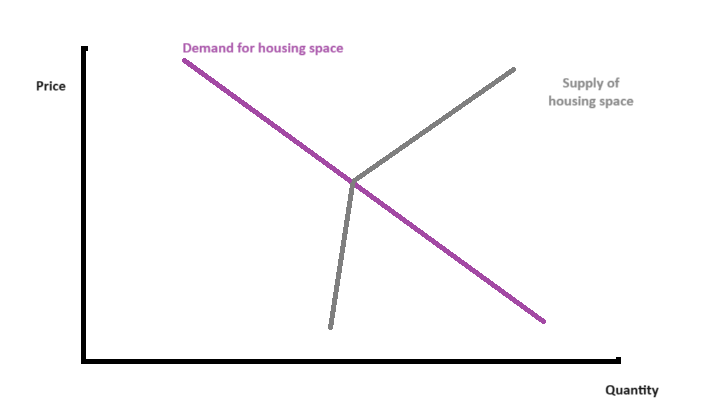

Should YIMBYs support or oppose greenfield growth? Two basic values animate most YIMBYs: housing affordability and urbanism. Sprawl puts those values into tension. Let’s take as a given that sprawl is “bad” urbanism, mediocre at best. Realistically, it’s rarely going to be transit-oriented, highly walkable, or architecturally profound. So the question is whether outward, greenfield growth is necessary to achieve affordability. And the answer from urban economics is yes. You can’t get far in making a city affordable without letting it grow outward. Model 1: All hands on deck Let’s start with a nonspatial model where people demand housing space and it’s provided by both existing and new housing. Existing housing doesn’t easily disappear, so the supply curve is kinked. A citywide supply curve is the sum of a million little property-level supply curves. We can split it into two groups: infill and greenfield, which we add horizontally. If demand rises to the new purple line, you can see that the equilibrium point where both infill & greenfield are active is at a lower price & higher quantity than the infill-only line. The only way to get some infill growth to replace some greenfield growth, in this model, is to raise the overall price level. And even then, the replacement is less than 1-for-1. Of course, this is just a core YIMBY idea reversed! In most U.S. cities, greenfield growth has been allowed and infill growth sharply constrained, so that prices are higher, total growth is lower, and greenfield growth is higher than if infill were also allowed. At the most basic level, greenfield growth is simply one of the ways to meet demand. With fewer pumps working, you’ll drain less of the flood. Model 2: Paying for what you demolish Now let’s look at a spatial model where people […]

On March 25, the city council of Burlington, VT, voted to pass a major zoning reform that one observer of Vermont politics (X.com’s pseudonymous @NotaBot) compared to the celebrated overhaul of Minneapolis’s zoning code. Burlington – the largest city in Vermont, at 45,000 inhabitants – has not escaped the housing crisis affecting the country. Burlington was an attractive destination for new residents during the pandemic and the rise of remote work; severe flooding last year put additional pressure on the housing supply. Policymakers statewide were well aware of the challenge and last year passed S.100, a sweeping package of housing reforms. Now Burlington, led by a pro-housing mayor, Miro Weinberger, has taken action at the local level. Burlington’s reform, known as the Neighborhood Code, is a welcome simplification of the city’s zoning. The Neighborhood Code eliminates the city’s ‘waterfront’ zoning districts and a ‘dense housing overlay’, adding a higher-density ‘residential corridor’ district, for a total of four residential zones. There are also significant increases in allowed density across the city. The Neighborhood Code allows up to fourplexes in all residential districts, allows townhouses everywhere but the low-density residential zone, and expands the option to create a cottage court or add a second freestanding unit on the same lot. The new code also limits requirements for minimum lot size, lot coverage, and setbacks. The reforms took some haircuts before final passage in response to pushback from organized groups of residents, but remain a meaningful change. In their report presenting the Neighborhood Code, Burlington’s city planning department reviews the city’s history. Planners explain that much of Burlington’s housing stock predates its zoning code, and in particular many existing lots are smaller than the official minimum lot size. Also, in Burlington’s first era of zoning, the city had a single residential district which […]

A friend asked what are the best papers supporting land use liberalization. That’s a broad question, but here are some of my answers. Affordability The basic case for zoning reform, across the political spectrum, is that the rent is too damn high. Michael Manville, Michael Lens, and Paavo Monkkonen give a combative and accessible review of the evidence in their Urban Studies paper (2020). The principal drawback is that it is rapidly becoming dated, as evidence and research come in from more recent reforms. The most important of those may be Auckland’s, which Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy has reported in a few papers, including this Economic Policy Center working paper (2023). Using a synthetic control method (which is not perfect, to be sure), Greenaway-McGrevy finds that upzoned areas had 21 to 33 percentage points less rent growth. A new candidate for the best review of the evidence on zoning reform and affordability is Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine M. O’Regan’s late 2023 working paper, “Supply Skepticism Revisited.” Racial integration Many authors from different disciplines have shown that both the intent and effect of zoning as practiced in the U.S. were racist and classist. That is, zoning policies have separated people by race, homeownership status, and income more than would have occurred in an unregulated market. Allison Shertzer, Tate Twinam, and Randall Walsh’s review of the evidence in Regional Science and Urban Economics (2022) is concise and helpful. However, fewer authors have attempted to show that removing specific zoning restrictions reduces existing patterns of segregation. One is Edward Goetz, in Urban Affairs Review (2021). He makes a qualitative argument. I’m unaware of a good causal, quantitative paper showing how broad upzoning impacts local integration (but I would happily commission it if anyone wants to write it!) Environment & climate Along some […]