Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

There’s a proposal to place a moratorium on all market rate construction in the Mission District, one of San Francisco’s most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods. Needless to say the proposal has sparked a debate. And Dan Ancona’s Putting Market Fundamentalism On Hold is another rock hurled into that particular fray. But in trying to take the anti-moratorium/pro-supply camp to task, it falls into the same unproductive bomb hurling we’ve been watching now for years. The following are a few thoughts on some of the points Mr. Ancona makes in his recent piece. Talking Past Each Other The first point is about a fundamental misunderstanding of the motivations behind the moratorium. Mr. Ancona makes this mistake, but so do the exasperated anti-moratorium/pro-supply advocates he quotes at the beginning of his piece. Hint: The moratorium is not about lowering housing prices. To be sure, the anti-moratorium camp wants lower aggregate housing prices throughout San Francisco and the entire region. The indisputable way to accomplish this goal is by building more housing. And as far as the anti-moratorium camp is concerned, this includes plenty of below market rate (BMR) construction to mitigate some of the distributional effects of development. For the pro-moratorium camp, however, this doesn’t cut it. Lower aggregate prices are not their goal. Their goal is keeping the existing population of the Mission intact and in place. Even a 70/30 ratio of market rate development to BMR construction wouldn’t do that. There would still be demographic churn and this is specifically what they want to avoid. For the pro-moratorium camp, lower housing prices are all well and good, but not if that means the dispersal of the existing community in the process. Searching for the Endgame The second issue is that there’s no endgame for the pro-moratorium camp. Mr. Ancona seems to think there is, but doesn’t go […]

“How to Make an Attractive City”, a video by The School of Life, recently gained attention in social media. Well presented and pretty much aligned with today’s mainstream urbanism, the video earned plenty of shares and few critiques. This is probably the first critique you may read. The video is divided into six parts, each with ideas the author suggests are important to make an attractive city. I will cover each one of them separately and analyze the author’s conclusion in a final section. 1 – Not too chaotic, not too ordered The author argues that a city must establish simple rules to to give aesthetic order to a city without producing excessive uniformity. From Alain Bertaud’s and Paul Romer’s ideas, it can make sense to maintain a certain order of basic infrastructure planning in to enable more freedom to build in private lots. However, this is not the order to which the video refers, suggesting rules on the architectural form of buildings. The main premise behind this is that it “is what humans love”. But though the producers of the video certainly do love this kind of result, it is impossible to affirm that all humans love a certain type of urban aesthetics generated by an urbanist. It is even less convincing when this rule will impact density by restricting built area of a certain lot of land or even raising building costs, two probable consequences of this kind of policy: a specific kind of beauty does not come for free. Jane Jacobs, one of the most celebrated and influential urbanists of the modern era, clearly argued that “To approach a city, or even a city neighborhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, […]

Seamless Transit is the new transportation policy report from SPUR. Main author Ratna Amin proposes integrating the Bay Area’s balkanized transit systems to improve lackluster ridership. Given that the region has 23 separate transit providers–more than any other metropolitan area in the country–she may have a point. The report proposes standardizing service maps, fare structures, and payment systems; eliminating inter-system coverage gaps as well as redundant coverage; and reforming transit governance so that the different agencies actually make plans together instead of working at cross-purposes or not at all. The recommendations are sound and the report includes historical footnotes for context. These are helpful for understanding region’s complicated institutional arrangements. Seamless Transit is a fine piece of work and well worth the read for anyone interested in Bay Area transportation. But while organizational efficiency is important, it’s not the only thing to discuss. If we want to improve the region’s mass transit systems, we have to consider the physical environment in which those systems are embedded. To get transit right, the region needs to embrace density. Denser development around transit nodes would increase ridership substantially. When people live, work, and play in smaller geographic areas, more people travel between a fewer number of points. Mass transit, especially fixed rail transit, becomes more effective the denser development becomes. Hong Kong’s Metro Transit Railway (MTR) might be the quintessential example of urban density begetting mass transit success. The city is home to over 7 million inhabitants. It has a population density of over 18,000 residents per square mile. And of this population, 41% live within a half mile of an MTR station. The result? The MTR has a farebox recovery ratio of 186%–the highest in the world. Because of legal as well as political differences between Hong Kong and the Bay Area, […]

Housing has a lot going against it in the California. But amidst all the legal, political, and regulatory roadblocks, there’s one law that sneaks by largely unnoticed: Prop 98. Prop 98 guarantees a minimum level of state spending on education each year. Sacramento pools most city, county, and special district property taxes into special education funds to meet this commitment. The localities only get to keep a small part of the property tax revenues for their own general budgets. This system creates a disincentive for cities to permit housing. New housing brings in new residents who need city services. But it doesn’t bring in a commensurate increase in property taxes since most of that revenue gets scooped up by Sacramento. Commercial development, though, brings in taxes a city gets to keep. Sales and hotel taxes are significant revenue streams. And they don’t cause the kinds of strain on city services that new residential does. Reforming Prop 98 might be low hanging fruit. Changing the formula to appropriate a broader stream of city revenues might help ease the bias against housing. And it might even be possible to amend the law without having to fight the California Teachers Association. As long as there’s no net decrease in education funding, of course. It’s tough to say exactly how much new housing Prop 98 actually prevents. Different cities get to keep different amounts of their property taxes, so the disincentive differs case to case. And there are plenty of other things like CEQA and Prop 13 which put a drag on new construction as well. But where CEQA and Prop 13 make it easier for residents who are already NIMBYs to gum up the works, Prop 98 is a reason in itself for a city to avoid residential development. So while we can’t do […]

Over at Greater Greater Washington, Ms. Cheryl Cort attempts to temper expectations of what she calls the “libertarian view (a more right-leaning view in our region)” on affordable housing. It is certainly reassuring to see the cosmopolitan left and the pro-market right begin to warm to the benefits of liberalization of land-use. Land-use is one area the “right,” in it’s fear of change, has failed to embrace a widespread pro-market stance. Meanwhile, many urban-dwellers who consider themselves on the “left” unknowingly display an anti-outsider mentality typically attributed to the right’s stance on immigration. Unfortunately, in failing to grasp the enormity of the bipartisan-caused distortion of the housing market, Ms. Cort resigns to advocate solutions that fail to deliver widespread housing affordability. Yes, adding more housing must absolutely be a part of the strategy to make housing more affordable. And zoning changes to allow people to build taller and more usable space near transit, rent out carriage houses, and avoid expensive and often-unnecessary parking are all steps in the right direction. But some proponents go on to say relaxing zoning will solve the problem all on its own. It won’t. Well, if “relaxing” zoning is the solution at hand, she may be right – relaxing will only help a tad… While keenly aware of the high prices many are willing to pay, Cort does not seem to grasp the incredible degree to which development is inhibited by zoning. “Relaxing” won’t do the trick in a city where prices are high enough to justify skyscrapers with four to ten times the density currently allowed. When considering a supply cap that only allows a fraction of what the market demands, one can not reasonably conclude “Unlimited FAR” (building density) would merely result in a bit more development here and there. A radically liberalized land-use regime would […]

This post draws heavily from Tom W. Bell’s “Want to Own a City?” and would not have been possible without his prior writing and research The “Right to the City” is an old marxist slogan that’s as catchy as it is ill-defined. Neither the phrase’s originator Henri Lefebvre, nor David Harvey, a more recent proponent, seem to have articulated the idea in any meaningful way. Even the Right to the City Alliance stops short of explaining what the right actually is. When it comes up, it’s typically alongside a claim that something is being stolen or taken away from long-standing communities, as if neighborhoods were sovereign territory suffering from an invasion. For practical purposes, no one has any right to reside in any place beyond their ability to pay. But if the desire is for a way in which communities could actually own the places they call home, perhaps the Right to the City should be a property right. Public Ownership through Private Property What’s the difference between a private company and a municipal corporation? You can own the former but not the latter. Investors have clearly delineated property rights in their corporations. Residents have no equivalent ownership rights in their cities. But what if living in a city meant owning a piece of it as a legal entity as well? Imagine that a city issued shares to its residents. Shares would vest over time and long-time residents would have more equity than new arrivals. Now assume that this city took in all of its revenue through land value taxation and that land revenues were used to pay dividends to the city’s resident-shareholders. Instead of facing displacement, incumbent residents would benefit from rising demand to live in their city. Shares might also be used to weight the voting system. More shares could […]

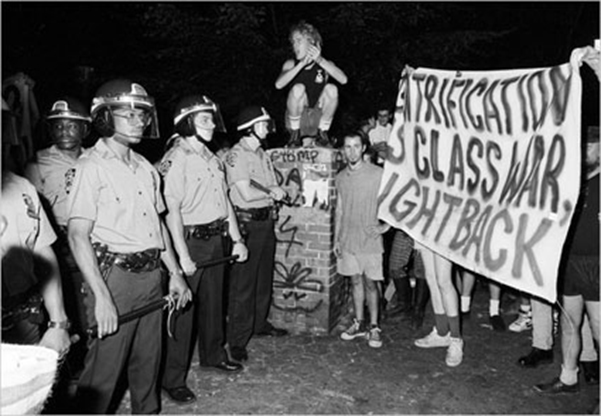

Gentrification is the result of powerful economic forces. Those who misunderstand the nature of the economic forces at play, risk misdirecting those forces. Misdirection can exasperate city-wide displacement. Before discussing solutions to fighting gentrification, it is important to accept that gentrification is one symptom of a larger problem. Anti-capitalists often portray gentrification as class war. Often, they paint the archetypal greedy developer as the culprit. As asserted in jacobin magazine: Gentrification has always been a top-down affair, not a spontaneous hipster influx, orchestrated by the real estate developers and investors who pull the strings of city policy, with individual home-buyers deployed in mopping up operations. Is Gentrification a Class War? In a way, yes. But the typical class analysis mistakes the symptom for the cause. The finger gets pointed at the wrong rich people. There is no grand conspiracy concocted by real estate developers, though it’s not surprising it seems that way. Real estate developers would be happy to build in already expensive neighborhoods. Here, demand is stable and predictable. They don’t for a simple reason: they are not allowed to. Take Chicago’s Lincoln Park for example. Daniel Hertz points out that the number of housing units in Lincoln Park actually decreased 4.1% since 2000. The neighborhood hasn’t allowed a single unit of affordable housing to be developed in 35 years. The affluent residents of Lincoln Park like their neighborhood the way it is, and have the political clout to keep it that way. Given that development projects are blocked in upper class neighborhoods, developers seek out alternatives. Here’s where “pulling the strings” is a viable strategy for developers. Politicians are far more willing to upzone working class neighborhoods. These communities are far less influential and have far fewer resources with which to fight back. Rich, entitled, white areas get down-zoned. Less-affluent, disempowered, minority […]

Co-authored with Anthony Ling, editor at Caos Planejado Gentrification Gentrification is the process through which real estate becomes more valuable and, therefore, more expensive. Rising prices displace older residents in favor of transplants with higher incomes. This shouldn’t be confused with the forced removal of citizens via eminent domain or “slum clearance.” Ejecting residents by official fiat is a different problem entirely. A classic example of gentrification is that of Greenwich Village, New York. Affluent residents initially occupied the neighborhood. It later became the city’s center for prostitution, prompting an upper-middle class exodus. Low prices and good location would later attract the textile industry. This was the neighborhood’s first wave of gentrification. But after a large factory fire, the neighborhood was once again abandoned. Failure, however, would give way to unexpected success: artists and galleries began to occupy the vacant factories. These old industrial spaces soon became home to one of the most important movements in modern art. In Greenwich Village, different populations came and went. And in the process they each made lasting contributions to New York’s economic and cultural heritage. This was only possible because change was allowed to take place. But change isn’t always easy. As a neighborhood becomes more popular, it also becomes more expensive. Tensions run high when long-time residents can’t afford rising rents. Some begin to call for rent controls or other measures to prevent demographic churn. But rent control is a temporary fix at best; in the longer term, its effects are negative. By reducing supply, rent control tends to drive up the cost of housing. And in the face of price controls, landlords may seek to exit the rental market entirely, further exacerbating any housing shortage. What, then, does this mean for urban development? How can cities evolve without completely displacing their middle and […]

Want to live in San Francisco? No problem, that’ll be $3,000 (a month)–but only if you act fast. In the last two years, the the cost of housing in San Francisco has increased 47% and shows no signs of stopping. Longtime residents find themselves priced out of town, the most vulnerable of whom end up as far away as Stockton. Some blame techie transplants. After all, every new arrival drives up the rent that much more. And many tech workers command wages that are well above the non-tech average. But labelling the problem a zero sum class struggle is both inaccurate and unproductive. The real problem is an emasculated housing market unable to absorb the new arrivals without shedding older residents. The only solution is to take supply off its leash and finally let it chase after demand. Strangling Supply From 2010 to 2013, San Francisco’s population increased by 32,000 residents. For the same period of time, the city’s housing stock increased by roughly 4,500 units. Why isn’t growth in housing keeping pace with growth in population? It’s not allowed to. San Francisco uses what’s known as discretionary permitting. Even if a project meets all the relevant land use regulations, the Permitting Department can mandate modifications “in the public interest”. There’s also a six month review process during which neighbors can contest the permit based on an entitlement or environmental concern. Neighbors can also file a CEQA lawsuit in state court or even put a project on the ballot for an up or down vote. This process is heavily weighted against new construction. It limits how quickly the housing stock can grow. And as a result, when demand skyrockets so do prices. To remedy this, San Francisco should move from discretionary to as-of-right permitting. In an as-of-right system, it’s much […]

Alain Bertaud is probably the most interesting urbanist you’ve haven’t heard about. He is a senior researcher at the NYU Stern Urbanization Project next to names such as Paul Romer and Solly Angel. Bertaud used to be the lead urbanist at the World Bank, and Ed Glaeser has said that everything he knows about land use restrictions in developing countries he has learned from Alain. Bertaud has also worked as a consultant and/or resident urbanist in cities such as Bangkok, San Salvador, Port-au-Prince, Sana’a, New York, Paris, Tlemcen and Chandigarh. Our Brazilian collaborator Anthony Ling, editor of Caos Planejado, met Bertaud at the NYU DRI conference last year entitled “Cities and Development: Urban Determinants of Success”, who gave us the following interview: AL: You are currently writing a book tentatively titled “Order Without Design”, which in some way relates to the title of our website, “Planned Chaos”. What do you mean by the title of your next book – what should readers expect of it? AB: “Order without design” is a quotation from Hayek that he uses in a different context in “The Fatal Conceit”: “Order generated without design can far outstrip plans men consciously contrive”. In the context of cities it means that cities themselves are mostly self generated by simple rules and norms applied to immediate neighbors but with overall design concept designed by one person or a group of designers. The spatial structure of large cities is a mix of top-down design and spontaneous order created by markets. Spontaneous order appears in the absence of a designer’s intervention when markets and norms regulate relationships between immediate neighbors. Most evolving natural structures, from coral reefs to starlings’ swarms, are created by spontaneous order. The objective of my book is to show that top-down design should be reduced to a minimum and much more room should […]