Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

One common argument against allowing the construction of taller apartment buildings is that tall buildings cost more to build, and thus are “overwhelmingly occupied by the wealthy.” For example, tall buildings, unlike houses and walk-up buildings, require elevators. But in fact, fairly tall buildings can be pretty cheap where demand is low and/or housing supply is high. For example, in East Cleveland, a low-income suburb of Cleveland, one 24-story building rents one bedroom apartments for as little as $552 per month, despite the fact that the building contains extras such as a pool and a fitness center. This means that (assuming rent should be no more than a quarter of income) someone earning less than $30,000 could afford this building. Even in nicer neighborhoods, older high-rises are not hugely expensive: for example, in midtown Atlanta, the Darlington’s apartments start at just over $700. It could be argued that because these buildings were built decades ago, their costs are not relevant to those of newer buildings. Certainly, newer high-rises are more expensive than older ones- but the same is true for newer walk-ups. To test this proposition, I focused on the outer boroughs of New York, using Zillow.com to focus on buildings built between 2010 and 2016. The cheapest newer apartment in Brooklyn started at $1150 (about $350 more than the cheapest older listing); the cheapest new elevator building started at $1600 (and included a doorman, thus inflating the rent beyond the basic amount caused by elevators). Similarly, in Queens the cheapest newer building rented for $1450 (over $600 more than the cheapest older listing), while the cheapest newer elevator building rented for $1550. In sum, it seems to me that the difference in cost between the cheapest high-rises and the cheapest low-rises, although not nonexistent, are not huge either.

On Thursday, the Massachusetts State Senate voted 23-15 to pass the zoning reform bill, S.2311, after approximately three hours of debate and amendments. 20 of the 63 amendments were adopted, with the rest either defeated or withdrawn. According to the Massachusetts Smart Growth Coalition, the bill directs municipalities to allow accessory dwelling units as-of-right in single-family residential districts; permits more as-of-right multifamily housing; reduces the number of votes needed to change zoning from a two-thirds majority to a simple majority; allows development impact fees; eliminates the need for special permits for some types of zoning; provides standards for granting zoning variances; establishes a training program for zoning board members; and lastly, modifies the process of creating a subdivision. One amendment that was defeated, proposed by Sen. William Brownsberger, removed a provision that would have required cities with an inclusionary zoning policy to offer concessions such as density bonuses. A provision from the first Senate version of the bill, S. 122, that would have allowed for consolidated permitting, was not enacted. Unlike past ones, this bill actually has teeth: the as-of-right multifamily provision establishes a minimum density of 8 units per acre for rural communities and 15 for others and if municipalities don’t comply, courts can provide relief. The bill was passed despite last-minute attempts to derail it by Sen. Bruce Tarr (R-Essex and Middlesex), who attempted to have it sent back to the Ways and Means Committee on the grounds that it had no public hearings since last September. This was rejected by the other senators, with Sen. Dan Wolf (D-Barnstable) saying he wished every bill was as fully vetted as S.2311. “We have fully vetted this, we are ready to move,” he said. “We need to update outdated zoning laws,” said Sen. Harriette Chandler (D-Worcester). “To recommit will serve nothing but […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Shane Phillips points the finger to a major culprit in LA‘s affordability problems: Keep Los Angeles Affordable By Repealing Proposition U Of the 29,000 acres zoned for commercial and industrial uses throughout LA, 70 percent saw their development capacity sliced in half, from a floor-area ratio (FAR) of 3.0 to 1.5. Since the city allows housing to be built in many of these zones, it didn’t just mean less office, retail, and manufacturing space, but fewer homes as well. Emily Washington contributed to New Urbs at The American Conservative: Family-Friendly Cities Start With Schools But where I depart from Schwarz is that public policy, not economic forces or renter preferences, is largely responsible for the lack of children in American cities. Specifically, education policy. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer took a writing break this week to wander around Texas, visiting the towns of Cuero, Victoria, Corpus Christi, Kingsville, Brownsville, McAllen, and the Mexican border city of Reynosa. He has since returned to Dallas, and will be flying this week to Boulder, CO, for the first annual YIMBY conference. Tickets for the event are still available. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group Alden Wilner creates a Wikipedia stub for Market Urbanism, Russ Nelson adds to it. We’d love to see the hive mind expand the page! Adam Millsap‘s latest: What The Boom And Bust Of Williston, ND Teaches Us About The Future Of Cities via Jonathan Coppage at New Urbs: Rescue Cities for Families Shanu Athiparambath wrote, Indian Cities Need Private Fire Stations Matt Robare sums up the Massachusetts zoning reform, which passed the Senate Alex Bernstein wants to know the best objective and unbiases books to start reading Asher Meyers suggest the benefit of Universal Basic Income extends to urban issues based on Charles Murray‘s editorial […]

In 1986, a foreshadowing of today’s fight over “neighborhood integrity” was taking place, culminating in November as Los Angeles residents voted 2-to-1 to cut the development potential of thousands of parcels across the city. Of the 29,000 acres zoned for commercial and industrial uses throughout LA, 70 percent saw their development capacity sliced in half, from a floor-area ratio (FAR) of 3.0 to 1.5. Since the city allows housing to be built in many of these zones, it didn’t just mean less office, retail, and manufacturing space, but fewer homes as well. The ballot initiative responsible for these changes was called Proposition U, and it’s the reason that so many commercial corridors in LA are still characterized by 1960s and ’70s-era, single-story, dilapidated strip malls. All those arterial corridors were the ones permanently frozen in time by Prop U. THE PROPOSAL To my knowledge no one has ever assessed exactly how much this instance of “planning by the ballot” actually reduced the residential capacity of Los Angeles. By my very, very rough estimate, I would put the number somewhere on the order of 1 million homes.* But whether the actual number is 1 million, 500K, or over 2 million, the conclusion is the same: If we want to keep Los Angeles affordable for residents at all income levels, we should repeal Proposition U. Repealing Proposition U would achieve several important aims. Since we’re talking about arterial, commercial corridors, the repeal would dramatically increase the supply of transit-oriented housing over the next several decades—something we desperately need at a time of record-low residential vacancy rates if we’re to have any hope of limiting continued rent increases. It would reduce development pressures on existing communities, directing development to underutilized corridors with little to no housing on them, rather than funneling developers into single-family neighborhoods […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Michael Lewyn dispels some common misconceptions about Jane Jacobs And High-Rises So I’m not sure she would have favored the common modern idea that high-rise and low-rise buildings should be segregated from each other, or that buildings of different density are “out of scale.” Despite auto-centric regulation and subsidies, Houston‘s “zoning lite” approach seems to be working, according to Nolan Gray in Houston’s Beautiful (yet Partial) Embrace of Market Urbanism This fourth city has managed to balance a booming economy, explosive population growth, and affordable housing. This city has—as cities have for thousands of years—steadily grown denser, more walkable, and more attractive to low-income migrants seeking opportunity. This city is Houston, and it’s well past time for her to come out of the shadows. 2. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group via Adam Hengels: a clip of a speech by Will Arnett’s character in Netfllix’s series “Flaked” who drops the Venice Beach NIMBYs and comes out as a YIMBY via Krishan Madan: “At a time of such high demand, higher density construction should be legalized” via Adam Hengels: Rethinking a Century of Zoning Andy Walker wants to know who’s going to be at CNU in Detroit this weekend via Krishan Madan: Van Bramer To Block Phipps’ 210-Unit [Affordable Housing] Development Plan, Essentially Kills Proposal (in Queens) Nick Zaiac shared an interesting table from NAHB, who found regulations to account for nearly 1/4 of the cost of new home prices Andrew Atkin shared his predictions of a “Utopian” sprawl, Urbanists cringe via Adam Millsap: Clean money, dirty system: Connected landowners capture beneficial land rezoning Nick Zaiac found some “Good stuff from the Richmond Fed on infrastructure, parking, and reform options” via Roger Valdez: HALA’S Most Confusing Recommendation: The Pushes and Pulls of MIZ (Seattle) via Roger Valdez: Seattle may slap new rules on Airbnb […]

A metropolitan economy, if it is working well, is constantly transforming many poor people into middle-class people, many illiterates into skilled people, many greenhorns into competent citizens. … Cities don’t lure the middle class. They create it. – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities If you follow urban issues in the press, you might be forgiven for thinking that there are only three cities in America: San Francisco, New York, and Portland. All three are victims of their own success, as rising demand for housing has increased rents to unsustainable levels. Despite their best efforts, from rent control to inclusionary zoning mandates, middle- and lower-class households are increasingly forced to leave these cities as each progressively transforms into a playground of the rich. Yet there is a fourth city, a city which must not be named except to be derided as a sprawling, suburban hellscape. This fourth city has managed to balance a booming economy, explosive population growth, and affordable housing. This city has—as cities have for thousands of years—steadily grown denser, more walkable, and more attractive to low-income migrants seeking opportunity. This city is Houston, and it’s well past time for her to come out of the shadows. Explosive Economic Growth, Booming Population, Functioning Housing Market Before jumping into the nitty-gritty of how Houston has handled explosive growth in the demand for housing, it is worth first getting a handle on the magnitude of the challenge facing the city. When many people think of the Houston economy, they understandably think of large energy companies. Indeed, energy companies dominated Houston’s economy for much of the last century and continue to play a major role today. But in the years following the 1980s oil glut, Houston’s economy has been diversified in large part by startups and emerging small […]

Since new urbanists (in my experience) tend to be very skittish of high-rise development, one might think that their ideological ancestor Jane Jacobs was one of these people who thought no building should be over five floors. But in her 1958 essay “Downtown Is For People,” she hinted at a very different view, describing New York City’s Lever House and Seagram Building as among the city’s “extraordinary crown jewels.” Similarly, she described San Francisco’s Union Square (which bordered buildings of wildly varying heights) as “the city at its best.” Jacobs was not against height–but she was against monotony. She wrote, for example, that Park Avenue should “have the most commercially astute and urbanite collection possible of one- and two-story shops, terraced restaurants, bars, fountains and nooks.” So I’m not sure she would have favored the common modern idea that high-rise and low-rise buildings should be segregated from each other, or that buildings of different density are “out of scale.”

1. This week at Market Urbanism Brent Gaisford sums up How Los Angeles’ Rent Got So Damn High Three big things happened, two of them awesome, and one dumb. We decided living in cities was cool again (awesome), city centers are creating tons of new jobs (awesome), and we didn’t build very many new places to live in our cities (not awesome). 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent his 6th and final week in San Antonio. His two Forbes articles this week were about how Subsidizing Light Rail Is Like Subsidizing The Landline Telephone and how Modern Zoning Would Have Killed Off America’s Dense Cities, which covered the New York Times research conducted by Stephen Smith If today’s regulatory climate had been applied a century or two ago, the American cities that people most want to preserve would be shells of themselves. And that was the point of the Times’ article, to show the fundamentally anti-urban nature of modern zoning regulations. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group Michael Lewyn‘s latest at Planetizen: Does New Housing Create New Demand for Housing? Rick Rybeck shared his writing: Funding Infrastructure to Rebuild Equitable, Green Prosperity via Krishan Madan: Will Bellevue Kneecap Development to Preserve Its Employees’ Views? via Bjorn Swenson: The “Grandma Test” says “speak up” Marcos Paulo Schlickmann wants to discuss whether the technology is a barrier to entry to less tech savvy Uber/Lyft customers John Coppage at American Conservative: Co-living shouldn’t just be for big-city yuppies via John Morris: Housing Costs Too Much: A Responsive Series of Awkward Dinner Conversations via John Morris: [Pittsburgh] Terminal Bldg converting to The Highline with bike trails and green space via Krishan Madan: SF Now Has Highest Per Capita Property Crime Rate In The US via Krishan Madan: For First Time in Modern Era, Living With Parents Edges Out Other Living Arrangements for […]

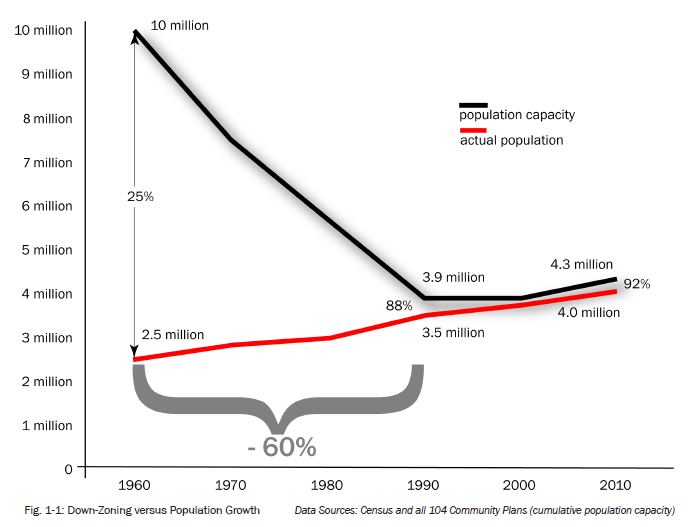

[Research help for this article was provided by UCLA student Hunter Iwig] The rent in LA has gone up 30% in the last three years. What the hell? Three big things happened, two of them awesome, and one dumb. We decided living in cities was cool again (awesome), city centers are creating tons of new jobs (awesome), and we didn’t build very many new places to live in our cities (not awesome). Living in cities is cool again (awesome) In the 1950s and 1960s our cities stopped growing and people started moving to the suburbs. We kept it up for a long, long time. But something has changed in the last 10-15 years. More and more people prefer to live in walkable, urban areas. Today, 52% of Americans say they would like to live in a place where they do not need to use a car very often. For millennials, it’s even higher – 63% say they want the walkable convenience of cities. City dwellers do less environmental damage and cause less traffic, so that sounds like pretty damn good news. Cities are creating tons of jobs (awesome) New jobs used to be created in suburbs. But since the Great Recession until 2011, that’s changed – cities are where the new jobs are. And, surprise surprise, people want to move to places where they can get jobs. We’ve made it incredibly hard to build more houses in LA and other cities (not awesome) First, a quick primer. You can’t build anything you want wherever you want. Zoning and planning rules dictate what can be built on any given plot of land. In 1960, L.A. had a population of 2.5 million, but its zoning rules allowed for housing for 10 million if every lot was built to it’s maximum density. Today our […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism: Emily Washington champions Market Urbanist ideas on The Federalist radio hour Tory Gattis contributed How Houston Can Grow Gracefully: Snow White And The Nine Dwarves Each of these “villages” could comfortably grow to as much as a million people themselves, which, when added to 2-3 million in Houston, gets us as high as 12 million people in the metro area. Adam Hengels wants to loosen up on exclusionary zoning before trying other schemes: Exclusionary Zoning and “Inclusionary Zoning” Don’t Mix Given that, by definition, zoning is exclusionary, Inclusionary Zoning completely within the exclusionary paradigm is synonymous with Inclusionary Exclusion. Anthony Ling contributed an article translated from Portugueses: Densifying Transit Corridors Is Not Densifying Enough Many factors justify TODs’ attractiveness to current planners, including that they make transit viable, increase the centrally-located housing stock, and satisfy residents of low-rise areas, who usually enjoy keeping their neighborhoods’ original features. Zach Caceres made sense of the philosophy of the late Zaha Hadid‘s partner: The Bottom-Up Urbanism Of Patrik Schumacher Markets and open exchange are a ‘robust information processing system’—the best that humans have yet found. Cities are also ultimately about structuring information. The built environment embodies generations of lessons learned by humanity, the evolution of a community reflected in its roads and walls, and the deliberate structuring of human affairs through architecture. Michael Lewyn found evidence that not many real people object to home sharing such as AirBnb: To Know Home-Sharing Is To Support It Only 4 percent of Americans think home-sharing should be illegal, and only 30 percent think it should be taxed. 52 percent think homesharing should be legal and untaxed. Even among self-described liberals, only 38 percent think homesharing should be taxed. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent his 5th week in San Antonio. This weekend he’s visiting the Mexican border town of Nuevo Laredo, and the famed old […]