Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Every so often during his tenure as mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg tried to push through congestion pricing, in which drivers would have to pay to use city streets in Midtown and Lower Manhattan. That’s a popular solution to chronic overcrowding but, like drinking coffee to try to cure a hang over, it doesn’t really get to the heart of the matter. More intervention usually doesn’t solve the problems that were themselves the result of a prior intervention. Let me explain. In 2011, I had the opportunity to participate in an online discussion over at Cato Unbound. It focused on Donald Shoup’s book The High Cost of Free Parking, which looks at the consequences of not charging for curbside parking. If you’ve ever tried to find a parking spot on the street in a big city, especially on weekdays, you know how irritating and time-consuming it can be. It may not top your list of major social problems, except perhaps when you’re actually trying to do it. In fact, according to Shoup about 30 percent of all cars in congested traffic are just looking for a place to park. The problem though is not so much that there are too many cars, but that street parking is “free.” Except, of course, it isn’t free. What people mean when they say that some scarce commodity is free is that it’s priced at zero. Some cities, such as London, Mayor Bloomberg’s inspiration, charge for entering certain zones during business hours — with some success. (As well as unintended consequences: People living in priced zones pay much less for parking and higher demand has driven central London’s real-estate prices, already sky high, even higher). But this doesn’t really address what may be the main source of the problem: the price doesn’t […]

The Cato Institute’s Vanessa Brown Calder is skeptical of the Obama administration’s suggestion that state governments can play a role in liberalizing land-use regulation, a policy area usually dominated by local governments. In an otherwise thoughtful post responding to a variety of proposals, she writes that federal and state-level bureaucrats should step aside to allow local advocacy groups to fill the void. She asks, “Who better to determine local needs than property owners and concerned citizens themselves?” Pretty much anyone, really. Local control of land-use regulation is a mistake and concerned citizens in particular are ill-suited for making decisions about their neighbors’ property. Supporters of free societies usually oppose local control of basic rights for good reason. Exercising one’s rights can be inconvenient for or offensive to nearby third parties. Protesters slow traffic, writers blaspheme, rock bands use foul words, post-apartheid blacks live wherever they choose with no regard for long-held South African social conventions, and so on. These inconveniences obviously don’t override rights to freedom of expression, but lower levels of government might be persuaded by people whose sensibilities are offended by these expressions. People are more likely to favor restrictions on rights when presented with a specific situation than they are when asked about general principles. People are even more likely to favor restricting a specific, disliked person’s rights. The landmark First Amendment case, National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, is instructive. The plaintiffs, American Nazis planning a parade through a neighborhood populated by Holocaust survivors in Illinois, sued on First Amendment grounds when the local government tried to prevent them from carrying swastikas. The Supreme Court eventually ruled in favor of the Nazis because the First Amendment protects peaceful demonstrations with no regard for the vile or hateful content of the ideas being promoted […]

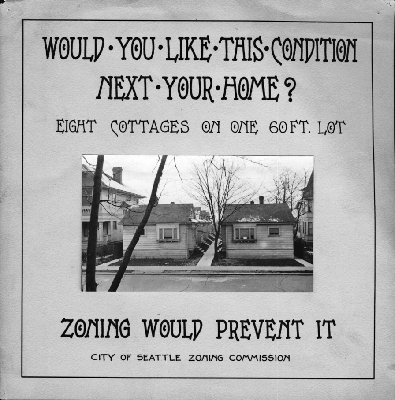

1. This week at Market Urbansim: The Invisible City by Sandy Ikeda It is this: A city—especially a great one—cannot really be seen. Paradoxically, the closest we can come to actually seeing one is through the imagination. Otherwise, it’s invisible. Moreover, if you can fully comprehend a place, then it’s not a city. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent his third week in San Diego. His Forbes article this week asks What Is The Best City In Texas? Not only is Houston Texas’ best city; it is among a handful of emerging ones in the U.S.—including Los Angeles, San Diego, Miami, Denver, Atlanta and Seattle—that will become the dense infill cities of tomorrow. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Emily Hamilton was interviewed on the Economics Detective podcast with Garrett Malcolm Petersen Brendon Harre wrote: Reciprocal intensification property rights Michael Hamilton wrote “another post about Obama‘s toolkit”: Who better to determine local needs than property owners and concerned citizens themselves? Roger Valdez wrote: Massachusetts Tries A New Solution For Chronic Homelessness Anders Mikkelsen shared a 1922 Seattle Zoning Commission post, arguing for zoning to keep out poor via Tom W Bell: The Tallinn experiment: what happens when a city makes public transport free? via David N Welton: The Neighbors Dilemma via Nolan Gray: Report: One Person Called In 84 Percent Of Dulles Noise Complaints via John Morris: Pentagon Video Warns of “Unavoidable” Dystopian Future for World’s Biggest Cities via David Iach: A Vision for a Chicago Unified by Rivers via Anthony Ling: As Land-Use Rules Rise, Economic Mobility Slows, Research Says 4. Elsewhere: Hey, Leonardo DiCaprio: true climate champions don’t fight against urban density David Roberts, Vox Wapo: There is no such thing as a city that has run out of room City Journal reviews a new biography about Jane Jacobs Reason Magazine […]

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is a short, often wonderful but consistently enigmatic (at least to me) novel about an extended conversation between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. Marco tells the Khan a series of tales about fantastical cities he’s perhaps only imagined. I’ve always assumed that the book’s title refers to that imaginary quality, since no one besides Marco himself has actually seen the cities he describes, and they likely exist only in his mind or in the words as he utters them. Recently, I hosted a couple of group “tours” of my neighborhood. These tours are called “Jane’s Walks” in memory of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. In the course of explaining her (mostly laissez-faire) principles to the group, I realized there’s another interpretation of Calvino’s title that I much prefer. It is this: A city—especially a great one—cannot really be seen. Paradoxically, the closest we can come to actually seeing one is through the imagination. Otherwise, it’s invisible. Moreover, if you can fully comprehend a place, then it’s not a city. You Don’t See a City on a Map If you think about a particular city that you know, what comes to mind? An image, a feeling, a smell, or a sound? Before we visit a city, we may look at pictures of parts of it, perhaps its famous landmarks, but these mean little to us in themselves. We may study a map of Paris to get a sense of the layout or the general shape of the metropolis. But what we are seeing is not the city of Paris but something highly abstract, abstracted not only from Paris but also from the particular reality of our lives. If, before going there, we could somehow look at a photo we will take of Paris, the scene would not evoke much from us […]

1. This week at Market Urbansim: Markets As Cities by Sandy Ikeda There is a deep affinity between cities and markets, and indeed between cities and liberty. (As the old saying goes, “City air makes you free.”) Cities aren’t merely convenient locations for markets; a living city (which I’ll define in a moment) is a market. MU Podcast Episode 04: Anthony Ling on Brazilian Cities and the Future of Transportation Anthony is founder and editor of Caos Planejado, a Brazilian website on cities and urban planning. He also founded Bora, a transportation technology startup and is currently an MBA candidate at Stanford University. He graduated Architecture and Urban Planning at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent his second week in San Diego, and this weekend is visiting Corona Del Mar in Orange County, where he’ll get a driving tour from some MU enthusiasts. His Forbes articles this week were America’s 20 Largest Metros Have Higher GDPs Than Most Foreign Nations and Austin’s Rail Transit Boondoggle, Further Explained Agencies like Austin’s CapMetro are dogmatic and unimaginative. They observe a top-down solution, such as rail transit, that may work in a few U.S. cities; they take the plan off the shelf and plop it into their own city, regardless of whether or not it fits; then, when the project fails miserably–as it has in many cities–they send out their press team to justify it, using every crackpot methodology. Scott will be returning November 9 to San Antonio to give a speech on the city’s economic emergence. Here’s a write-up about the event by the San Antonio Business Journal. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Louise Ortensia asks “Capitalism for urbanists? Pretty redundant, isn’t it?” An interesting dialogue ensues… David Welton asks “has anyone here contacted local politicians in […]

My guest this week is Anthony Ling. Anthony is founder and editor of Caos Planejado, a Brazilian website on cities and urban planning. He also founded Bora, a transportation technology startup and is currently an MBA candidate at Stanford University. He graduated Architecture and Urban Planning at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and worked with Isay Weinfeld early in his career. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Be sure to check out Caos Planejado. Whether Portuguese is your native language or you’re interested in Brazilian urban planning issues, it’s a fantastic resource. Learn more about the emergent order of informal favela development. Everyone interested in urban planning should, at the very lease, read the Wikipedia article on Brasilia. Learn more about on-demand transit. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

Why are a growing number of libertarians fascinated by cities and indeed pinning their hopes for a freer future on cities? Two examples of this just from recent Freeman issues are by Zachary Caceres on startup cities and the winner of the Thorpe-Freeman Blog Contest, Adam Millsap, responding to one of the articles in an entire cities-themed issue. There is a deep affinity between cities and markets, and indeed between cities and liberty. (As the old saying goes, “City air makes you free.”) Cities aren’t merely convenient locations for markets; a living city (which I’ll define in a moment) is a market, and the first cities probably originated as markets. Much has been written on this connection, but I’d like to point out another link between cities and markets—one that comes from the great 20th century urbanist, Jane Jacobs. Consciously or not, Jacobs followed the tradition of the influential German sociologist Max Weber in seeing cities as essentially markets. Indeed, in her 1969 book The Economy of Cities, she defined a city, or what I like to call a “living city,” as “a settlement that consistently generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Moreover, I’ve written elsewhere that today’s economic phenomena of demand, supply, the price system, markets, externalities, public goods, and division of labor had their genesis in an urban setting. The fundamental (classical) liberal concepts of property rights, economic freedom, and the rule of law did not develop among wandering nomads, farmers, or in small villages but perforce from the interactions of strangers with diverse cultures and backgrounds interacting in dense proximity with one another. Diversity… In her great book of 1961, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs first presented her argument that the key feature of any great city is its diversity. […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism: 4 Things Austin’s City Council Could Do Today To Fight The Housing Shortage by Dan Keshet Central Austin needs more housing. Prices have been rising, more and more people want to live where they have short commutes, but are only able to afford homes near the periphery. We have a long-term plan to alter our land development code in a way that would help…but our need is now. What options are available today? Spillovers: Knowledge, Beer, and Technology by Sandy Ikeda I don’t think anyone could reasonably contest that technology has reduced the need for some kinds of proximity. It’s the tired hyperbole that “science obliterates distance” and the like that gets my goat. The gulf between “reducing” and “eliminating” is too vast. Where Do Upzonings Happen? by Chris Bradford What NIMBYs are really after is limiting access to neighborhood amenities, mostly by limiting the quantity of housing. Neighborhoods (at least the ones empowered politically) do their best to hold housing below the market-clearing quantity. Book Review: The Well-Tempered City by Emily Hamilton a review of a book by Jonathan F. P. Rose In the vein of Jane Jacobs and F.A. Hayek, Rose identifies that cities are “wicked” problems rather than engineering problems that policymakers can solve through tinkering. In spite of this recognition of the complexity of cities’ interrelated systems, Rose asserts that cities need visionaries to address problems from obesity to climate change from the top down. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer has changed his schedule. He thought San Diego would be a pass-through stop this week on the way to Los Angeles. But he found “America’s Finest City” surprisingly dense, and decided to stay all of October. His two Forbes articles this week were about The Millennials Transforming San Antonio and […]

This book review is part of a TLC Book Tour. The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life by Jonathan F. P. Rose In The Well-Tempered City, real estate developer Jonathan F. P. Rose offers a sweeping history of cities and equally grandiose policy proposals to improve urban outcomes. In the vein of Jane Jacobs and F.A. Hayek, Rose identifies that cities are “wicked” problems rather than engineering problems that policymakers can solve through tinkering. In spite of this recognition of the complexity of cities’ interrelated systems, Rose asserts that cities need visionaries to address problems from obesity to climate change from the top down. Rose leads with the most interesting section of his book on the origins of early cities. In support of his theory that great cities are built by visionaries, he focuses on ancient cities that were founded around religious sites, including Uruk and Teotihuacan, downplaying the path of great cities emerged organically from trading posts, like Venice or Rotterdam. He advocates for the benefits of orderly urban layouts like Hippodamian plan or the magic square that ancient Chinese cities followed. A theme running throughout the book is that American urban planning has embraced the Western values of individualism and free will while giving short shrift to the Eastern value of harmony, such as the unification that comes from top-down urban design. In support of more cohesive plans, Rose downplays the incredible progress that has been possible through decentralized urban and economic development. Throughout the book, Rose argues that American cities are suffering from a lack of vision from their planners. Unlike ancient leaders who built grand temples and imposing walls, today’s planners focus on enforcing rules rather than defining a city’s aesthetics. He writes: It turns out that a city can pick any […]

I think the most useful way to think about NIMBYism is as a neighborhood-centered phenomenon. When people shop for homes, they shop for specific, physical features of a dwelling, of course, but mainly they shop for neighborhoods. The quality of neighborhood amenities — interpreted broadly to include things like school quality and access to the CBD — varies wildly from neighborhood to neighborhood, and thus does the amount people are willing to pay for those amenities. What NIMBYs are really after is limiting access to neighborhood amenities, mostly by limiting the quantity of housing. Neighborhoods (at least the ones empowered politically) do their best to hold housing below the market-clearing quantity. This ensures that the value of neighborhood amenities is capitalized into home prices. Without quantity controls, the “nicest” neighborhoods would be the densest. Instead, thanks to zoning, they’re simply the most expensive. There’s a steep premium for buying into the neighborhood club. Here’s evidence in favor of the “club” theory from L.A. planner C.J. Gabbe. (H/t Urbanize.LA.) Gabbe asks the question, “Where do upzonings and downzonings happen?” To answer it, he looked at how the zoning of each of L.A.’s 780,000 parcels changed between 2002 and 2014, and tallied whether a lot was “upzoned” or “downzoned”, as measured by the change in allowed residential density. The first striking result was how few of the parcels were either upzoned or downzoned: an average of just 225 acres were upzoned and 216 acres downzoned annually between 2002 and 2014. That is, less than two-tenths of one percent of L.A.’s land area was upzoned or downzoned each year. Given the surge in demand for housing in L.A., especially over the last 6 years or so, that’s remarkably little. But the other thing Gabbe documents is that resistance to zoning really does seem to […]