Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

This post was originally published at mises.org and reposted under a creative commons license. It’s no secret that in coastal cities — plus some interior cities like Denver — rents and home prices are up significantly since 2009. In many areas, prices are above what they were at the peak of the last housing bubble. Year-over-year rent growth hits more than 10 percent in some places, while wages, needless to say, are hardly growing so fast. Lower-income workers and younger workers are the ones hit the hardest. As a result of high housing costs, many so-called millennials are electing to simply live with their parents, and one Los Angeles study concluded that 42 percent of so-called millennials are living with their parents. Numbers were similar among metros in the northeast United States, as well. Why Housing Costs Are So High? It’s impossible to say that any one reason is responsible for most or all of the relentless rising in home prices and rents in many areas. Certainly, a major factor behind growth in home prices is asset price inflation fueled by inflationary monetary policy. As the money supply increases, certain assets will see increased demand among those who benefit from money-supply growth. These inflationary policies reward those who already own assets (i.e., current homeowners) at the expense of first-time homebuyers and renters who are locked out of homeownership by home price inflation. Not surprisingly, we’ve seen the homeownership rate fall to 50-year lows in recent years. But there is also a much more basic reason for rising housing prices: there’s not enough supply where it’s needed most. Much of the time, high housing costs come down to a very simple equation: rising demand coupled with stagnant supply leads to higher prices. In other words, if the population (and household formation) is […]

We've finalized the lineup for the Market Urbanism track at #FEEcon 2017 June 15-17 and it's loaded with great sessions from urbanists, economists, and activists. Don't forget, you can use the code MU40off for a 40% discount.

The far-left “TruthOut” web page recently published an attack on YIMBYs,* describing them as an “Alt-Right” group (despite the fact that the Obama Administration is pro-YIMBY). I was surprised how little substance there was to the article; most of it was various ad-hominem attacks on YIMBY activists for cavorting with rich people. I only found two statements that even faintly resembled rational arguments. First, the article suggests that only current residents’ interests are worth considering in zoning policy, because “the people who haven’t yet moved in” most often means the tech industrialists, lured by high salaries, stock options and in-office employee benefits like massage therapists and handcrafted kombucha.” This statement is no different than President Trump’s suggestion that Mexican immigrants “[are] bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” – that is, it is an unverifiable (if not bigoted) generalization about large numbers of people. Furthermore, it doesn’t make sense. The “tech industrialists” have the money to outbid everyone else, so they aren’t harmed by restrictive zoning. Second, the article states that academic papers aren’t as relevant as the actual experiences of San Franciscans displaced by high housing costs. In response to the argument that less regulation means cheaper housing, it states “tell that to people like Iris Canada, the 100-year-old Black woman who had used local regulations to stay in her home of six decades, only to be evicted in February.” So in other words, somebody was evicted in San Francisco, therefore San Francisco’s restrictive zoning prevents eviction. I don’t see how the latter follows from the former. The whole point of the YIMBY/market urbanist argument is that if there was more housing, there would be lower housing costs, hence fewer evictions. *For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, YIMBY means “Yes In My Back Yard”, a […]

Caos Planejado, in conjunction with Editora BEI/ArqFuturo, recently published A Guide to Urban Development (Guia de Gestão Urbana) by Anthony Ling. The book offers best practices for urban design and although it was written for a Brazilian audience, many of its recommendations have universal applicability. For the time being, the book is only available in Portuguese, but after giving it a read through, I decided it deserved an english language review all the same. The following are some of the key ideas and recommendations. I hope you enjoy. GGU sets the stage with a broad overview of the challenges facing Brazilian cities. Rapid urbanization has put pressure on housing prices in the highest productivity areas of the fastest growing cities and car centric transportation systems are unable to scale along with the pace of urban growth. After setting the stage, GGU splits into two sections. The first makes recommendations for the regulation of private spaces, the second for the development and administration of public areas. Reforming Regulation Section one will be familiar territory for any regular MU reader. GGU advocates for letting uses intermingle wherever individuals think is best. Criticism of minimum parking requirements gets its own chapter. And there’s a section a piece dedicated to streamlining permitting processes and abolishing height limits. One interesting idea is a proposal to let developers pay municipalities for the right to reduce FAR restrictions. This would allow a wider range of uses to be priced into property values and create the institutional incentives to gradually allow more intensive use of land over time. Meeting People Where They Are Particular to the Brazilian experience is a section dedicated to formalizing informal settlements, or favelas. These communities are found in every major urban center in the country and often face persistent, intergenerational poverty along with […]

Marcos Paulo Schlickmann, a transportation specialist and collaborator at Caos Planejado, our Brazilian partner website, recently interviewed Professor Donald Shoup, who answered questions about private and public parking issues. Private parking Marcos Paulo Schlickmann: What is your opinion on legal parking minimums? Donald Shoup: In The High Cost of Free Parking, which the American Planning Association published in 2005, I argued that minimum parking requirements subsidize cars, increase traffic congestion, pollute the air, encourage sprawl, increase housing costs, degrade urban design, prevent walkability, damage the economy, and penalize poor people. Since then, to my knowledge, no member of the planning profession has argued that parking requirements do not cause these harmful effects. Instead, a flood of recent research has shown they do cause these harmful effects. Parking requirements in zoning ordinances are poisoning our cities with too much parking. Minimum parking requirements are a fertility drug for cars. MPS: What would happen if we were to abandon parking minimums? DS: Reform is difficult because parking requirements don’t exist without a reason. If on-street parking is free, removing off-street parking requirements will overcrowd the on-street parking and everyone will complain. Therefore, to distill 800 pages of The High Cost of Free Parking into three bullet points, I recommend three parking reforms that can improve cities, the economy, and the environment: Remove off-street parking requirements. Developers and businesses can then decide how many parking spaces to provide for their customers. Charge the right prices for on-street parking. The right prices are the lowest prices that will leave one or two open spaces on each block, so there will be no parking shortages. Prices will balance the demand and supply for on-street parking spaces. Spend the parking revenue to improve public services on the metered streets. If everybody sees their meter money at work, the new public services can […]

Sandy Ikeda has led a Brooklyn Heights Jane’s Walk every year since 2011 in celebration of Jane Jacobs’ 101st birthday. Meet at the steps of Borough Hall (facing the Plaza and fountain) Sunday May 7th at 12:15. When you think of a city you like, what comes to mind? Can a city be a work of art? How do parked cars serve pedestrians? Most of the interaction among people, bikes, and cars is unplanned. How does that happen? Why do people gather in some places and avoid others? Is it possible to create a neighborhood from the ground up? What is a “public space”? How can the design of public space promote or retard social interaction? The beautiful and historic neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights offers excellent examples of Jane Jacobs’s principles of urban diversity in action. Beginning at the steps of Brooklyn¹s Borough Hall, we will stroll through residential and commercial streets while observing and talking about how the physical environment influences social activity and even economic and cultural development, both for good and for ill. We will be stopping at several points of interest, including the famous Promenade, and end near the #2/3 subway and a nice coffeehouse. To Find a Jane’s Walk near you, visit http://janeswalk.org/

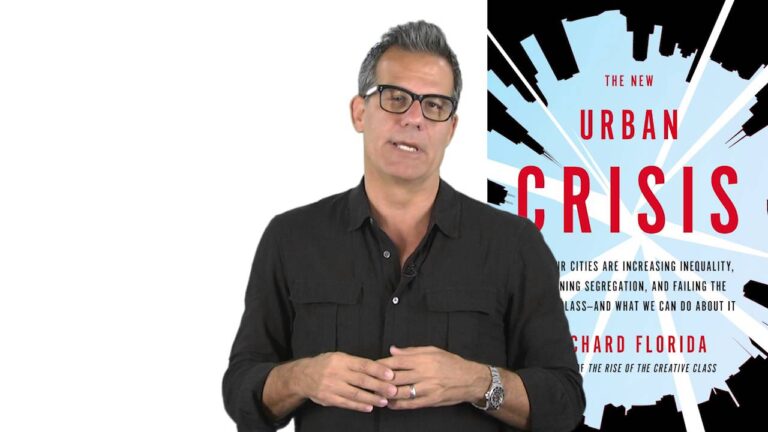

1. Announcements: Get ready for Market Urbanism at #FEEcon June 15-17 in Atlanta. Market Urbanists can use the code MU40OFF to get 40% off. We’ll have several other exciting announcements over the next few days. We can’t wait to see you there! If you are in New York, Market Urbanism is pleased to be a partner of Smart Cities NYC ’17: Powered by People, May 3-6. (smartcitiesnyc.com). The offer code SCNYC100 gets market urbanists a $100 ticket discounted down from the $1,200 standard price. Sandy Ikeda has a short clip in the film Citizen Jane: Battle for the City. Go see it!! Sandy Ikeda‘s Annual Jane’s Walk in Brooklyn Heights is this Sunday at 12:15. Vince Graham, former Chairman of the South Carolina Transportation Infrastructure Bank and friend of Market Urbanism published an op-ed in the Charleston Post and Courier: Unhealthy S.C. appetite for roads demands a diet 2. Recently at Market Urbanism: Market Urbanist Book Review: Cities and The Wealth of Nations by Jane Jacobs by Matthew Robare It seems like just about everyone who has ever set foot in a major city has read The Death and Life of Great American Cities and most professional urban planners have embraced at least part of her ideas. But that was not the only book she wrote and the others deserve attention from urbanists. Government-Created Parking Externalities by Emily Hamilton Developers are not responsible for creating a traffic congestion externality. Rather, city policymakers create this externality when they provide free or underpriced street parking. They cause drivers to waste time and gas sitting in traffic. Parking is not a public good that needs to be publicly-provided; it’s both rivalrous and excludable. Richard Florida and Market Urbanism by Michael Lewyn Florida writes that part of this “crisis” is the exploding cost of housing in some […]

I just finished reading Richard Florida’s new book, The New Urban Crisis. Florida writes that part of this “crisis” is the exploding cost of housing in some prosperous cities. Does that make him a market urbanist? Yes, and no. On the one hand, Florida criticizes existing zoning laws and the NIMBYs who support them. He suggests that these policies not only raise housing prices, but by doing so harm the economy as a whole. For example, he writes that if “everyone who wanted to work in San Francisco could afford to live there, the city would see a 500 percent increase in jobs… On a national basis, [similar results] would add up to an annual wage increase of $8775 for the average worker, adding 13.5 percent to America’s GNP – a total gain of nearly $2 trillion” (p 27). On the other hand, Florida is not ready to endorse the idea that “we can make our cities more affordable… simply by getting rid of existing land use restrictions” because “the high cost of land in superstar neighborhoods makes it very hard if not impossible, for the private market to create affordable housing in their vicinity. Combine the high costs of land with the high costs of high-rise construction and the result is more high-end luxury housing.” (p. 28). I don’t find his point persuasive, for a variety of reasons. First, as I have written elsewhere, land prices are often quite volatile. Second, the overwhelming majority of any region’s housing is not particularly new; even in high-growth Houston, only 2 percent of housing units were built after 2010. Thus, new market-rate housing is likely to affect rents by affecting the price of older housing, rather than by bringing new cheap units into the market. Florida also writes that “too much density can […]

In new research on parking policy in the Journal of Economic Geography, Jan Brueckner and Sofia Franco argue that residential developers should be required to provide more off-street parking in places where street parking contributes to traffic congestion. They argue that because traffic congestion is a negative externality, off-street parking requirements improve urban living. But street parking only contributes to traffic congestion when policymakers underprice it. Rather than addressing the externality of a government-created problem with new regulations, cities should price their street parking appropriately. Brueckner and Franco’s argument relies on the assumption that off-street parking will be under-provided without government intervention. They argue that because drivers circle their destination looking for free or cheap street parking, minimum parking requirements make people better off. The authors are correct in arguing that street parking contributes to the problem of traffic congestions. Parking guru Donald Shoup estimates that drivers who are circling around looking for parking spots make up 30 percent of downtown traffic. Cruising for parking imposes an external cost on others by causing everyone to waste time in slow traffic. While, Brueckner and Franco actually cite Shoup’s work on street parking and traffic congestion, they ignore his insight that when parking is priced appropriately, cities can eliminate this externality. The incentive to cruise for parking originates with public policy when city officials provide street parking at below-market prices. When parking prices are high enough, drivers will leave some parking availability on each block, eliminating the cruising problem without the need for minimum parking requirements. San Francisco’s SFPark program provides an example of successful implementation of variable pricing based on demand. SFPark has the goal of maintaining one to two available spots on each block so that drivers don’t contribute to traffic congestion while they’re looking for parking. When street parking is priced high […]

No one writer of the last 60 years has influenced urban planning and thinking as much as Jane Jacobs. It seems like just about everyone who has ever set foot in a major city has read The Death and Life of Great American Cities and most professional urban planners have embraced at least part of her ideas. But that was not the only book she wrote and the others deserve attention from urbanists. First published in 1984, Cities and the Wealth of Nations was her last book to focus on cities and her second concerned with economics. Conceived at the height of 1970s stagflation, Jacobs brought her considerable polemical skills to bear on macroeconomics and elaborated on the observations in The Economy of Cities. In that book she theorized that economic expansion in cities was driven by trade, innovation and imitation in a process she called “import replacement”. In this one she extended the idea, arguing that cities and not nation-states are the real basic units of macroeconomic life. She also examined how the economic expansion affected regions in differing geographic proximity and how import-replacement and the wealth generated by it can be used in ways that ultimately undermine the abilities of cities to create wealth, which she called transactions of decline. Import-replacement is one of Jacobs’ more controversial ideas, partially because it seems similar to a discredited development policy called import substitution and partially because her evidence is largely anecdotal, as Alon Levy wrote back in 2007. Nevertheless it’s the centerpiece of Jacobs’ economic theories. And dismissing her work based on a lack of conventional credentials ignores her entire rise to fame and influence. Two important things distinguish import-replacement from import-substitution. Substitution is a national policy pursued by governments with taxes, tariffs and subsidies while replacement is a process […]