Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In yesterday’s post, I showed that missing middle housing, as celebrated in Daniel Parolek’s new book, may be stuck in the middle, too balanced to compete with single family housing on the one hand and multifamily on the other. But what about all the disadvantages that middle housing faces? Aren’t those cost disadvantages just the result of unfair regulations and financing? Indeed, structures of three or more units are subject to a stricter fire code. It’s costly to set up a condo or homeowners’ association. Small-scale infill builders don’t have economies of scale. Those, and the other barriers to middle housing that Parolek lays out in Chapter 4, seem inherent or reasonable rather than unfair. In particular, most middle housing types cannot, if all units are owner-occupied, use a brilliant legal tradition known as “fee simple” ownership. Fee simple is the most common form of ownership in the Anglosphere and it facilitates clarity in transactions, chain of title, and maintenance. Urbanists should especially favor fee simple ownership of most city parcels because it facilitates redevelopment. Consider a six-plex condominium nearing the end of its useful life: to demolish and redevelop the site requires bringing six owners to agreement on the terms and timing of redevelopment. A single-owner building can be bought in a single arms-length transaction. It’s no coincidence that the type of middle housing with the greatest success in recent years – townhomes – can be occupied by fee-simple owners, combining the advantages of owner-occupancy with the advantages of the fee simple legal tradition. Many middle housing forms enjoy their own structural advantage: one unit is frequently the home of the (fee simple) owner. By occupying one unit, a purchaser can also access much lower interest rates than a non-resident landlord. (This is thanks to FHA insurance, as Parolek […]

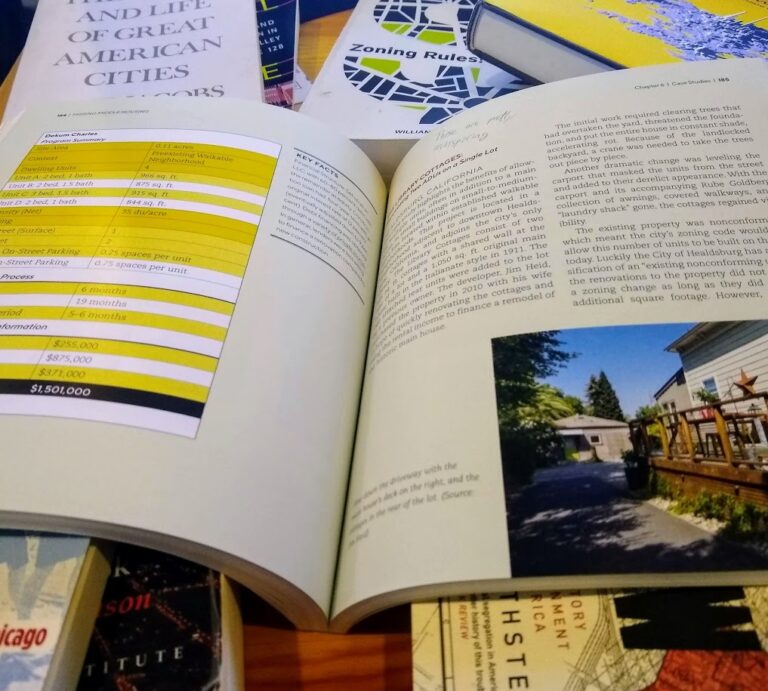

Everybody loves missing middle housing! What’s not to like? It consists of neighborly, often attractive homes that fit in equally well in Rumford, Maine, and Queens, New York. Missing middle housing types have character and personality. They’re often affordable and vintage. Daniel Parolek’s new book Missing Middle Housing expounds the concept (which he coined), collecting in one place the arguments for missing middle housing, many examples, and several emblematic case studies. The entire book is beautifully illustrated and enjoyable to read, despite its ample technical details. Missing Middle Housing is targeted to people who know how to read a pro forma and a zoning code. But there’s interest beyond the home-building industry. Several states and cities have rewritten codes to encourage middle housing. Portland’s RIP draws heavily on Parolek’s ideas. In Maryland, I testified warmly about the benefits of middle housing. I came to Missing Middle Housing with very favorable views of missing middle housing. Now I’m not so sure. Parolek’s case for middle housing relies so much on aesthetics and regulation that it makes me wonder whether middle housing deserves all the love it’s currently getting from the YIMBY movement. Can middle housing compete? Throughout the book, Parolek makes the case that missing middle construction cannot compete, financially, with either single-family or multifamily construction. That’s quite contrary to what I’ve read elsewhere. In a chapter called “The Missing Middle Housing Affordability Solution”, Daniel Parolek and chapter co-author Karen Parolek write: The economic benefits of Missing Middle Housing are only possible in areas where land is not already zoned for large, multiunit buildings, which will drive land prices up to the point that Missing Middle Housing will not be economically viable. (p. 56) On page 81, we learn, It’s a fact that building larger buildings, say a 125-150 unit apartment […]

The Manhattan Institute, a conservative (by New York standards) think tank, recently published a survey of New York residents; a few items are of interest to urbanists. A few items struck me as interesting. One question (p.8) asked “If you could live anywhere, would you live…” in your current neighborhood, a different city neighborhood, the suburbs, or another metro area. Because of Manhattan’s high rents, high population density, and the drumbeat of media publicity about people leaving Manhattan, I would have thought that Manhattan had the highest percentage of people wanting to leave. In fact, the opposite is the case. Only 29 percent of Manhattanites were interested in leaving New York City. By contrast, 36 percent of Brooklynites, and 40-50 percent of residents in the other three outer boroughs, preferred a suburb or different region. Only 23 percent of Bronx residents were interested in staying in their current neighborhood, as opposed to 48 percent of Manhattanites and between 34 and 37 percent of residents of the other three boroughs. Manhattan is the most dense, transit-dependent borough- and yet it seems to have the most staying power. So this tells me that people really value the advantages of density, even after months of COVID-19 shutdowns and anti-city media propaganda. Conversely, Staten Island, the most suburban borough, doesn’t seem all that popular with its residents, who are no more eager to stay than those of Queens or Brooklyn. Having said that, there’s a lot that this question doesn’t tell us. Because no identical poll has been conducted in the past, we don’t know if this data represents anything unusual. Would Manhattan’s edge over the outer boroughs have been equally true a year ago? Ten years ago? I don’t know. Another question asked people to rate ten facets of life in New York […]

I just read a 2018 book by a variety of authors (most notably Jonathan Levine, author of Zoned Out), From Mobility to Accessibility: Transforming Urban Transportation and Land Use Planning. The key point of the book is that rather than focusing solely on “mobility”, planners should focus on “accessibility”. What’s the difference? The authors describe mobility as speed or the absence of congestion; thus, a new highway that saves suburban commuters a few seconds increases mobility. “Accessibility” means making it easy for people to reach as many major destinations as possible, regardless of the mode of transport. For example, allowing more housing near downtowns and other urban job centers increases accessibility because it makes it easier for more people to live near work. However, residents of these neighborhoods might oppose such housing based on concerns about mobility; that is, they might fear that new neighbors might reduce mobility by increasing traffic. Obviously, an emphasis on increasing accessibility favors more compact development: people benefit from living closer to work, even if they are not driving 80 miles an hour. It also seems to me that the emphasis on accessibility favors more market-oriented land use policies; in the absence of government control, landowners will naturally want to increase accessibility by building housing near job centers and vice versa.

If there’s one thing that unites TV and film since the fifties, it’s the archetype of the dastardly developer – forever destroying homes and hiking rents. But it wasn’t always this way. Where did this trope come from, and is it true? This week on Pop Culture Urbanism, I dig into the cronyism and red tape that turned developers into Hollywood’s favorite villain. Be sure to follow future episodes by subscribing to the Pacific Legal Foundation on YouTube! We have a lot of content in the hopper that you won’t want to miss.

Has the Water Tribe gone full NIMBY? Can Avatar Aang overcome his angry impulse to preserve? Why is Ba Sing Se so segregated? And what can we learn from the success of Republic City? In this week’s episode of Pop Culture Urbanism, we explore the trade-offs and complications that every growing city has to deal with, including fictional cities of Avatar: The Last Airbender. Be sure to follow future episodes by subscribing to the Pacific Legal Foundation on YouTube! We have a lot of content in the hopper that you won’t want to miss.

Nolan Gray plunges into the Sam Raimi "Spider-Man" trilogy to uncover the housing problems (and solutions) of expensive cities like New York.

In 2015, urban studies professor Anne Haila published a book on Singapore’s land ownership and housing system called Urban Land Rent: Singapore as a Property State. The Singapore housing model has recently been getting some attention for its widespread homeownership and affordability relative to high-cost coastal cities in the United States. Both Haila and, recently, writers at Bloomberg and CityLab approach Singapore uncritically. And Singapore’s housing market does offer some key lessons to the United States. But unlike the story Haila and some other U.S. commentators have told, it has its downsides. Singapore’s housing market works much better for households near the middle of its income distribution relative to the highest-cost U.S. regions, but provides severely inadequate housing for its low-income migrant workers. The Mechanics of Singapore’s Public Housing In Singapore, 90% of the land is government-owned, and about 80% of citizens and legal residents live in owner-occupied public housing on leased land. Extensive government landholdings and a leasehold system date back to the country’s colonial era. Following Singaporean independence in 1965, the People’s Action Party, which has been in power ever since, has expanded state land holdings. At independence, about 50% of Singapore was government-owned, reaching its current level of holdings in 2002. Government land ownership has been accomplished through eminent domain along with land reclamation, which has increased the size of the island by a quarter. Government land is auctioned for housing and other types of development primarily as 99-year leases. The Housing and Development Board (HDB), a government agency, builds the majority of new housing, but some higher-end housing is privately developed. The HDB and private developers compete for land at auctions, and both pay market prices for it. Unlike the U.S. public housing system under which units remain government-owned and are leased to low-income tenants, Singapore’s […]

Charles Marohn’s recent article in The American Conservative on the evils of single-family zoning received over 200 comments. The most provocative responses were the ones forthrightly defending exclusion, on the grounds that renters are dangerous and must be excluded at all costs. For example, one person wrote: “People of all races also have a right to escape from uncivil society… Renters are entirely different in their outlook and practices than home owners in how one regards their neighborhood. For one it transactional, for the other its their dream and investment.” In other words, homeowners are better citizens, and thus must be protected from disorderly renters. What’s wrong with this argument? If you really believe homeowners are better citizens, you would want homeownership to be as cheap as possible, so that more people could become homeowners. For example, you would be positively eager to have small, cheap houses in homeowner zones, or even for-sale condos. But homeowners have a financial incentive to do the opposite: to make home ownership as scarce and expensive as possible, so they can sell their house for as much money as possible (or to use a common euphemism, to “build wealth”). And they usually favor zoning policies that do exactly that- that is, by excluding smaller, cheaper-to-build houses, inflate home prices and make homeownership unaffordable for many people. In other words, government can encourage home ownership as a source of alleged good citizenship, and can try to make home ownership a source of vast wealth- but it can’t do both. In the United States (and especially on the coasts) local government has chosen the latter path.

This book, available from solimarbooks.com, is a set of very short essays (averaging about three to five pages) on topics related to urban planning. Like me, Stephens generally values walkable cities and favors more new housing in cities. So naturally I am predisposed to like this book. But there are other urbanist and market books on the market. What makes this one unique? First, it focuses on Southern California, rather than taking a nationwide or worldwide perspective (though Stephens does have a few essays about other cities). Second, the book’s short-essay format means that one does not have to read a huge amount of text to understand his arguments. Because the book is a group of short essays, it doesn’t have one long argument. However, a few of the more interesting essays address: The negative side effects of liquor license regulation. Stephens writes that the Los Angeles zoning process gives homeowners effective veto power over new bars. As a result, the neighborhood near UCLA has no bars, which in turn causes UCLA students go to other neighborhoods to drink, elevating the risk to the public from drunk driving. The Brooklyn Dodgers’ move to Los Angeles; Los Angeles facilitated the transfer by giving land to the Dodgers- but only after a referendum passed with support from African-American and Latino neighborhoods. On the other hand, the construction of Dodger Stadium displaced a Latino community. To me, this story illustrates that arguments about “equity” can be simplistic. Los Angeles Latinos were both more likely than suburban whites to support Dodger Stadium, yet were more likely to be displaced by that stadium. So was having a stadium more equitable or less equitable than having no stadium? (On the other hand, a stadium that displaced no one might have been more equitable than either outcome). […]