Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Some weeks ago, I was participating in a Zoom discussion on NIMBYism, and someone asked: are Republicans and conservatives more pro-housing than Democrats and liberals, or less so? After examining some poll data, I discovered that the answer depends on how the question is asked. A 2023 Yougov poll asked respondents to choose between two alternative views: “People should be free to buy land and develop real estate where they please” and “The government should limit where people are allowed to build things.” 64 percent of Republicans favored the free-market option, as opposed to only 47 percent of Democrats. Similarly, a 2023 California poll asked Californians whether state government should “ease current land use and environmental restrictions to increase the supply of housing.” 64 percent of Republicans favored less regulation, as opposed to only 48 percent of Democrats. Similarly, 62 percent of conservatives and only 49 percent of liberals favored less regulation. Thus, it seems that where development issues are framed as a choice between government regulation and freedom, Democrats are more pro-regulation and Republicans more pro-freedom. Where questions about regulation exclude the magic word “government”, partisan differences become a bit narrower. A July 2022 Yougov poll asked about removing “Regulations and codes that prevent developers from constructing more housing”. Republicans favored the free-market answer by a 43-40% margin, while Democrats disagreed by a 45-38% margin. Polls that don’t directly reference regulation sometimes show that Democrats are more pro-housing. For example, a June 2022 Yougov poll asked respondents whether more apartments should be built: 83 percent of Democrats said yes, as opposed to 68 percent of Republicans. When asked whether more apartments should be built in respondents’ “local area”, the Democratic percentage dropped to 74 percent, and the Republican percentage to 50 percent. When a poll asks generally about “density” […]

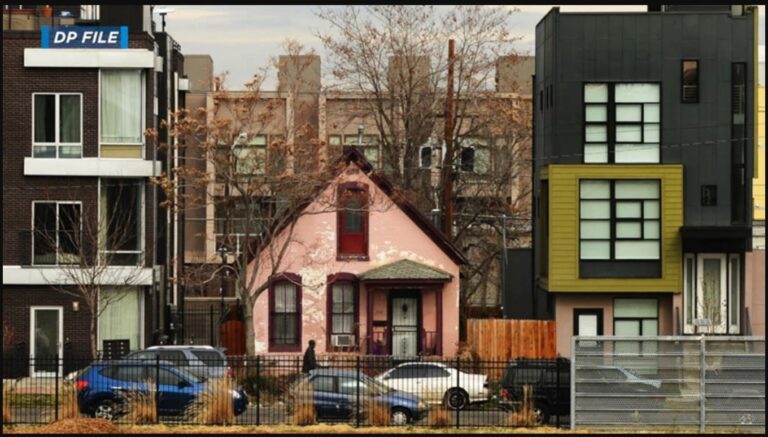

In many cities, poor people occupy valuable urban land close to downtown jobs, amenities, and transit. They can afford to live there because the housing stock in inner areas is usually older. If it hasn’t been completely renovated, the result can be quite cheap, even if the land is pretty valuable. In areas where there’s already some gentrification pressure, landlords face a timing problem: they can renovate (or sell to a developer) now, and cash out. Or they can hoard the property and wait until prices rise, supplying low-cost housing in the meantime. Land value taxes are specifically designed to penalize the hoard-and-wait approach by raising the annual tax cost of sitting on valuable land. It is specifically designed to accelerate neighborhood change. That’s the point. That’s what it says on the tin. Gentrification isn’t the only urban problem, and maybe it’s a small enough urban problem that a land value tax is a good idea anyway. But I think most of the benefits of Georgism can be unlocked with George-ish schemes (like renovation abatements or vacant land taxes) that are more narrowly designed.

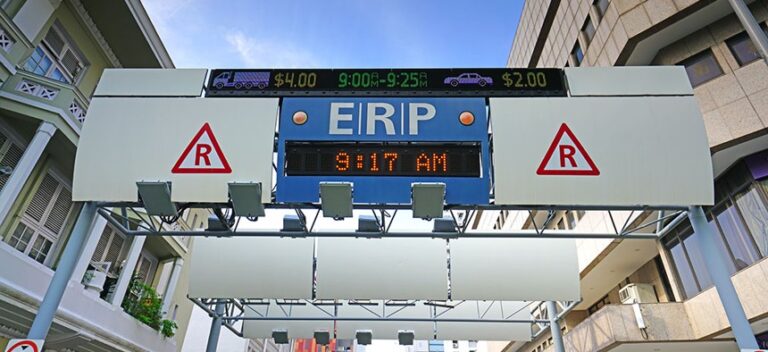

In a series of recent posts, Tyler Cowen has taken the view that congestion prices in major downtowns are a bad idea. This is what one might expect of a typical New Jerseyan, but not a typical economist. The writing in these posts is a bit squirrelly (or is it Straussian?), but as best I can make out, Tyler is deviating from the mainline economic views of externalities and prices by arguing a few points: Urban serendipity and growth are high-value externalities quite distinct from the usual efficiencies of combining large amounts of capital and labor in downtown office towers. Occasional visitors to the city find very high value there (presumably via a long-right-tail distribution) including by creating demand for new goods Congestion pricing will (a) decrease the number of people in the city, (b) particularly high-value visitors. He also makes some specific critiques of the mechanism design of the proposed NYC congestion charge. It’s worth getting that right, but let’s leave the technicalities aside here. Tyler’s points – as I’ve summarized (or mangled) them – seem like a mix of reasonable and wrong, although in several cases difficult if not impossible falsify. I’ll tackle these points in a completely irresponsible order. 2. Distinguished visitors On the second point: Diminishing marginal returns is enough to give Tyler’s argument the benefit of the doubt. The first visit to a symphony or subway likely has a bigger inspirational impact than the seventh or seven-hundredth. And outsiders may bring insights to the city in an Eli-Whitney-and-the-cotton-gin way. But for consuming new goods? Perhaps visitors’ demand is enough to sustain new imitations of low-end consumer goods (like a McDonalds in Chennai, if there is one). But for narratives of urban creativity, I prefer Malcolm Gladwell’s account of Airwalk shoes or Peter Thiel’s identification of […]

The state of Massachusetts lets municipal governments choose how strictly they regulate energy efficiency in buildings. Fifty-two of the state’s municipalities use the base building code, whereas 299, including Boston, have opted into the stricter “stretch” energy code. In addition to these two, the state recently rolled out an even stricter “specialized” stretch code in the interest of getting to net-zero carbon emissions faster. Cities could opt in to the specialized code as of last December; several municipalities have already opted in, and Boston may do so soon. The new code is technically the Municipal Opt-In Specialized Stretch Energy Code, and I considered referring to it hereinafter as MOISSEC, which is cute because it sounds like a wine, but I ended up deciding that the least confusing option is to follow official documents in referring to the new option as the specialized code, and refer to what is existing law in most of the state as the stretch code. Given that Massachusetts has some of the most expensive housing in the country, it’s reasonable to worry about the impact of any housing regulations on affordability, even when they serve an important objective. Massachusetts had the third highest cost of new housing of all states in 2021, and has unusually low housing supply, even among expensive coastal states. Research from the Boston Foundation details the extent of the problem: Greater Boston has lower vacancy rates than even Los Angeles or New York, homes spend less time on the market in Boston, and Boston is not on track to meet its housing production goals, though construction has increased somewhat in recent years. A new report released Tuesday by the MIT Center for Real Estate, the Home Builders and Remodelers Association of Massachusetts (HBRAMA), and Wentworth Institute of Technology (WIT) projects the impact […]

“Renting in Providence puts city councilors in precarious situations.” That was the Providence Journal’s leading headline a few days ago, as the legislature waited for Governor Daniel McKee to sign a pile of housing-related bills (Update: He signed them all). Rhode Island doesn’t have a superstar city to garner headlines, but it’s housing costs have mounted as growth has crawled to a standstill. But unlike in Montana and Washington, Rhode Island’s were largely procedural, aiming to lubricate the the gears of its existing institutions rather than directly preempting local regulations. House Speaker Joseph Shekarchi (D-Warwick), who championed the reforms, clearly drew on his professional expertise as a zoning attorney to identify areas for procedural streamlining. Specific and objective Six bills transmitted to the governor cover the general rules affecting most Rhode Island zoning procedures: S 1032 makes it easier to acquire discretionary development permission. Municipalities cannot enforce regulations that make it near-impossible to build on legacy lots that do not meet current regulatory standards. Municipalities can more quickly issue variances and modifications. (Rhode Island draws a unique distinction between minor and substantial variances, labeling the former “modifications” and subjecting them to a simpler process. A substantial variance must go before a board for approval; a modification can be approved administratively unless a neighbor objects. Municipalities must issue “specific and objective” criteria for “special use permits”, otherwise those use are automatically allowed as of right. That phrase – specific and objective – shows up again and again in Speaker Shekarchi’s bills. S 1033 requires that zoning be updated to match a municipality’s own Comprehensive Plan within 18 months of a new plan’s adoption. It also requires an annually updated “strategic plan” for each municipality, although the content and legal force of the strategic plans are unclear to me. S 1034 broadly […]

Today’s Wall Street Journal includes a front-page article about sky-high lawyer incomes. The article points out that top lawyers can earn $15 million per year or more. Why is this relevant to urbanism or markets? Because one common argument against new condos (at least in NYC) is that they will be bought by foreign investors instead of by local residents. In turn, this argument rests on the assumption that new housing is so expensive that the local rich can’t afford it. But someone who earns $15 million per year can afford almost all new condos, even in Manhattan. When I bought a condo in Atlanta many years ago, the sticker price was about 2.6 times my salary. Even if you assume no one will pay more than that, this means that a $15 million household can pay for a $39 million condo. Almost every new condo in Manhattan costs less than $39 million. My latest zillow.com search reveals that 541 units in condos and co-ops were built in 2020 or later. Only seven of those units cost over $39 million. In fact, only 34 cost over $15 million, and the majority (376 of the 541) cost under $5 million- certainly far more than I could ever afford, but affordable even for an attorney earning $1 or 2 million per year.

One common NIMBY* argument is that new housing (or the wrong kind of new housing) will “destroy the neighborhood.” For example, one suburban town’s politicians fought zoning reform in New York by claiming that allowing multifamily housing “is a direct assault on the suburbs.“ Indeed, many people do seem to believe that apartments and houses are somehow incompatible. But I saw an interesting counterexample recently. A couple of weeks ago, I attended the CNU (Congress for the New Urbanism) conference in Charlotte, North Carolina. CNU usually sponsors neighborhood tours, and I toured Myers Park, one of the city’s richest neighborhoods. Myers Park was built in the 1910s; most blocks are dominated by large single-family houses with an enormous tree canopy. Although Myers Park is only a couple of miles from downtown Charlotte, it certainly looks suburban, if by “suburban” you mean low-density and dominated by houses. (According to city-data.com, the neighborhood density is just below 4000 people per square mile, less than that of affluent Long Island suburbs like Great Neck and Cedarhurst). And yet on one of the neighborhood’s major streets (Queens Road) apartments and houses seemed to alternate. This does not seem to have reduced home values; the average value of detached homes there is over $1 million, about four times the statewide average. Moreover, Myers Park apartments are not the sort of “missing middle” housing that is virtually indistinguishable from a house. I saw a five-story building in Myers Park: not a skyscraper but definitely not something that looks like its neighbors. Not far away is a four-story building that looks like it has a few dozen units. In other words, apartments and houses can coexist, even in places that are very suburban in many ways. *As many readers of this blog probably know, NIMBY is an […]

In a recent Mackinac Policy conference, Detroit’s Mayor Mike Dugan proposed *drum roll* a land value tax. Sort of. Mayor Dugan’s proposal would create separate tax rates for land and capital improvements (i.e. the buildings on top). Specifically, he wants to decrease the tax rate on buildings by ~30% and increase rates on land by ~300%. The change would increase revenue for the city and also cause a series of second order effects. Taxing Blight & Rewarding Investment Detroit’s existing tax structure disincentives development. Holding vacant land or land with dilapidated (i.e. assessed as worthless) structures is cheap from a tax perspective. Actually developing land triggers a tax increase because of the brand new structure who’s value gets figured into the tax bill. What’s worse, the existing tax system encourages land hoarding. Land speculators sit on neglected parcels on the off chance that a developer needs it as part of a larger project. To caveat that, though, not all land speculation is bad. Holding some land off market and releasing it later into a development cycle can have positive benefits. In Detroit’s case, however, these are mostly vacant lots and abandoned buildings creating public health hazards the city has to deal with. The Political Economy of Land Value Taxation Unexpectedly – for me as a latte sipping coastal urbanite in California – Dugan’s LVT would also lower tax bills for homeowners. Land values in Detroit are low — in absolute terms and relative to structure values. Making the shift to taxing the less valuable land component of a property nets out positive for most homeowners. And the fact that it’s a win for homeowners makes me think it’s politically viable, both in Detroit and elsewhere. In places struggling to get back on a growth footing — places where land values […]

As various housing reform bills work their way through the lawmaking process in American state legislatures, several new legal challenges to local land use and zoning ordinances are simultaneously underway in state and federal courts. Among these courtroom efforts are challenges to occupancy restrictions, short-term rental bans, inclusionary zoning and single-family zoning itself. On May 9, 2023, the Pacific Legal Foundation filed a complaint on behalf of two plaintiffs in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas challenging a City of Shawnee ordinance (Ordinance No. 3419) which prohibits more than three unrelated adults from living together in a single residence. These limits, often adopted by localities as a means of excluding student renters or other groups of persons who are perceived as subverting the proper purpose of the so-called single-family home, are challenged by the plaintiffs as a violation of the constitutional right of free association and specifically the right to select and establish a household. The lawsuit also alleges that the ordinance violates equal protection and is beyond the scope of Kansas’ zoning enabling act (K.S.A. 12-741 et seq.), which does not authorize cities to regulate persons based upon blood or legal relationship. In Nevada, the Clark County District Court on February 16, 2023 issued a preliminary injunction blocking Clark County from implementing and enforcing certain sections of its short-term rental ban (Clark County Code, Title 7, Chapter 7.100, Sections 7.100.110-.260). The lawsuit, filed by the Greater Las Vegas Short Term Rental Association, alleges among other things that the ordinance is arbitrary and capricious, reads as unconstitutionally vague, infringes on free association and effects a taking of property. That ruling has now been appealed to the Supreme Court of Nevada. On December 15, 2022, the Institute for Justice commenced a lawsuit on behalf of a Seattle […]

In a pair of posts, Scott Alexander goads his mostly-YIMBY readers by claiming to believe that density is likely to increase prices. To quantify his readers’ views, he laid out a thought experiment in a Google poll, the results of which we’ll no doubt see in a few days. You can see the poll – and my answer – below. As a YIMBY scholar, I mood-affiliate with the first answer, but I chose the middle one because there is a fundamental misunderstanding between pro-housing people like me and Scott’s recent posts. Housing growth is not the same as city densification Scott’s experiment isn’t a “housing growth” experiment, it’s a “city densification” experiment. Crucially, he requires “proportional increases in the number of office buildings, schools, etc”. That is, the experiment would increase office space at the same pace as housing even though office vacancy rates (19%) are far higher than housing vacancy rates (~1.7%). Oakland is a pretty balanced city: as best I can tell from simple Census data, it probably has a jobs/residents ratio pretty close to the California average (by contrast, San Francisco has twice the state jobs/resident ratio). If Scott ran his experiment in a bedroom community, or stipulated that office space is left under current regulations, I’d have an easy time coming down on the “less expensive” side of the ledger. The point of the YIMBY movement is that housing faces uniquely strict regulation. California cities (and those in some other states) believe that offices and industrial uses are “taxpayers”, generating more revenue than they use in services. Housing is viewed as a fiscal cost. Regulation (“fiscal zoning“) and discretionary decisions have reflected this bias for decades. The result is headlines like “SF added jobs eight times faster than housing since 2010.” If Oakland upzoned citywide, it […]