Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

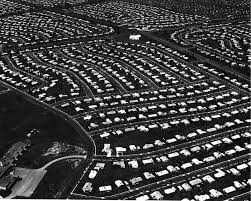

The alternative title for this piece was: “Ballot Box Zoning: Where Needed Housing Goes to Die.” Next month, Los Angeles will be voting on Measure S, a proposed 2-year policy that will effectively serve as a moratorium on new construction. That is, Measure S will require a public vote on any new development that does not fit within existing zoning. Most of the city’s major leaders, including Mayor Eric Garcetti, have come out against the measure, and the Los Angeles Times followed suit just a few days ago. I’m not going to rehash arguments for or against the measure. Instead, I’m going to offer several warnings based on the experience of Davis, CA, which passed its own Ballot Box Zoning Measure in 2000. Measure J, our ballot box zoning measure, requires voter approval on any attempt to change the zoning designation of open space or agricultural land that sits on the community’s edges. The law also explicitly names two particular parcels that must be voted on prior to approval. So for the purposes of this piece, consider it a ballot box zoning law targeting sprawl. Warning 1: These Measures Are Hard To Roll Back Measure J passed in Davis with just 53.6% percent of the vote in a March primary when residents cast just 19,000 votes (in a city with at least 49,000 voting-age residents). The law contained a renewal clause, and when it came up for renewal in 2010, support jumped to 76.7% percent. This increased support may be an artifact of how the opposition attempted to stall the measure’s renewal. Opponents of the renewal made a NIMBY argument the centerpiece of their case: they argued that slowing growth at the edge of town meant more infill pressure in the city’s core, threatening the character of neighborhoods. As I’ll discuss in a […]

As a Market Urbanism reader, you are hopefully fluent in the problems of exclusionary zoning. If you’re new to the term, there are some good pieces on the topic here and here. Basically: exclusionary zoning is the use of zoning to price people out of a community. The classic example is minimum lot sizes or minimum unit sizes: cities only zone parcels big enough to ensure low-income families cannot afford the housing. When subsidies for affordable housing require specific unit attributes, like reduced parking ratios, a community can simply require parking ratios above that threshold (although states can move swiftly to stamp out such practices). States have also responded to exclusionary zoning practices with a wide array of policy interventions known collectively as “anti-snob laws.” One key component of California’s anti-exclusionary efforts is called the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA). The law requires each jurisdiction in the state to produce a Land Inventory (or Adequate Sites Inventory, or Sites Inventory, or Buildable Land Inventory) that demonstrates the jurisdiction possesses space to accommodate anticipated housing needs at adequate densities. Read “adequate densities” as dense enough to produce affordable units. Scott Wiener, the state senator representing San Francisco, is pushing to give the RHNA some real teeth. The most contentious component of the process is the definition of “need” for each jurisdiction. The state calculates anticipated need based on population and jobs projections for each region. Regional councils of government (COGs) are then empowered to distribute the regional need to each jurisdiction within that region. Need is quantified in terms of units, and these needed units are further categorized into four groups: units affordable to Very Low Income, Low Income, Moderate Income, and Above Moderate Income households. Regional agencies had some flexibility in making these allocations in the past. Thanks to SB 375, which passed in […]

President Trump has threatened to withhold all federal funds from so-called sanctuary cities–municipal governments that do not enlist their police departments in the president’s mass deportation plan. If he makes good on his threat, cities that insist on maintaining their sanctuary status can offset revenue losses with two policies: liberalizing land-use regulation and depoliticizing public land sales. It’s unclear exactly how much money each city would lose by maintaining its sanctuary status, but New York City, to name one example, relies on federal funding for 10% of its budget, according to state comptroller estimates. A sudden drop of that magnitude would devastate many jurisdictions, and Miami-Dade County has already caved. However, a handful of cities with high rents and very restrictive land-use regulations could dramatically increase property tax revenue and the value of city-owned real estate through liberalization. Millions of Americans would love to live in cities like New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, San Jose, Austin, Portland, and Denver, but legal restrictions on what can be built limit the number of housing units available and increase the cost of each unit. Some estimates have found that regulation alone accounts for fifty percent of the cost of housing in San Francisco. At the same time, land-use regulation has the opposite effect on the price of land itself. A plot of land with limited legal potential for development is worth much less than a plot a developer could use to build a large, lucrative building. Economist Keith Ihlanfeldt has found that the decrease in land values more than offsets the increase in home prices—meaning some cities are decreasing potential revenues by restricting development. San Francisco has large neighborhoods of single-family homes where rent levels would sustain large apartment towers. The drastic mismatch between what is currently allowed and what consumers demand suggests that land values would skyrocket if restrictions were relaxed. […]

Stanford economist Paul Romer has proposed an intriguing concept: the “charter city.” A charter city is a newly created city governed by a country other than the one within whose borders it exists. Its residents would remain citizens of the home country. Romer offers Hong Kong as an example when it was a British colony. According to the Charter Cities website: The two prerequisites for a charter city are uninhabited land and a charter granted and enforced by an existing government or collection of governments. With the right rules, a city will naturally grow as residents arrive, employers start firms, and investors build infrastructure and buildings. What makes a charter city attractive is the prospect of rapidly instituting rules consistent with economic development in an area that might otherwise take decades to do so, offering almost overnight the chance of a better life for the citizens of a impoverished country for whom long-distance immigration is too costly. Thus Romer has suggested that a charter city be established in Haiti for Haitians left homeless by the recent earthquake and who have little hope of help from an ineffective and otherwise corrupt Haitian government. (The Charter Cities site, however, says the time is not right for this option.) While I find myself largely sympathetic to the concept, two things bother me about it. Incentive Problems The first is whether it can overcome the Public Choice problem. Although the Hong Kong example is persuasive, I wonder whether the host country would really permit the guest country to bypass enough of its political and bureaucratic interests to establish an effective rule of law, free exchange, and other things necessary for long-term economic development. And once established, would the host permit enough free immigration from its own jurisdiction and the loss of long-established political bases […]

Urban Institute Press • 2005 • 494 pages • $32.50 paperback In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Nelson argues that while all levels of American government have been expanding since World War II, people have responded with a spontaneous and massive movement toward local governance. This has taken two main forms. The first is what he calls the “privatization of municipal zoning,” in which city zoning boards grant changes or exemptions to developers in exchange for cash payments or infrastructure improvements. “Zoning has steadily evolved in practice toward a collective private property right. Many municipalities now make zoning a saleable item by imposing large fees for approving zoning changes,” Nelson writes. In one sense, of course, this is simply developers openly buying back property rights that government had previously taken from the free market, and “privatization” may be the wrong word for it. For Nelson, however, it is superior to rigid land-use controls that would prevent investors from using property in the most productive way. Following Ronald Coase, Nelson evidently believes it is more important that a tradable property right exists than who owns it initially. The second spontaneous force toward local governance has been the expansion of private neighborhood associations and the like. According to the author, “By 2004, 18 percent—about 52 million Americans—lived in housing within a homeowner’s association, a condominium, or a cooperative, and very often these private communities were of neighborhood size.” Nelson views both as positive developments on the whole. They are, he argues, a manifestation of a growing disenchantment with the “scientific management” of […]

I just read a law review article complaining that some white areas in integrated southern counties were trying to secede from integrated school systems (thus ensuring that the countywide systems become almost all-black while the seceding areas get to have white schools), and it occurred to me that there are some similarities between American school systems and American land use regulation. In both situations, localism creates gaps between what is rational for an individual suburb or neighborhood and what is rational for a region as a whole. In particular, it is rational for each suburb to have high home prices (because that means a bigger tax base)- but I don’t think San Francisco-size rents and home prices are rational for a region as a whole. Similarly, it is rational for each individual neighborhood within a city to have restrictive regulations, because if one neighborhood is less restrictive it suffers from whatever burdens might result from new housing, without the broader benefit of lower citywide housing costs. How are school districts similar? Since the prestige of a neighborhood is related to its school district, and the prestige of school districts depends on their socio-economic makeup, it is rational for each suburb (or city neighborhood) to be part of a school district dominated by white children from affluent families, rather than to be part of a socially and racially diverse district. But if every middle-class or affluent area draws school district lines in a way that excludes lower-income children, the poor people are all concentrated in a few poor school districts (such as urban school districts in Detroit and Cleveland). Is this rational for the region as a whole? I suspect not.

The Cato Institute’s Vanessa Brown Calder is skeptical of the Obama administration’s suggestion that state governments can play a role in liberalizing land-use regulation, a policy area usually dominated by local governments. In an otherwise thoughtful post responding to a variety of proposals, she writes that federal and state-level bureaucrats should step aside to allow local advocacy groups to fill the void. She asks, “Who better to determine local needs than property owners and concerned citizens themselves?” Pretty much anyone, really. Local control of land-use regulation is a mistake and concerned citizens in particular are ill-suited for making decisions about their neighbors’ property. Supporters of free societies usually oppose local control of basic rights for good reason. Exercising one’s rights can be inconvenient for or offensive to nearby third parties. Protesters slow traffic, writers blaspheme, rock bands use foul words, post-apartheid blacks live wherever they choose with no regard for long-held South African social conventions, and so on. These inconveniences obviously don’t override rights to freedom of expression, but lower levels of government might be persuaded by people whose sensibilities are offended by these expressions. People are more likely to favor restrictions on rights when presented with a specific situation than they are when asked about general principles. People are even more likely to favor restricting a specific, disliked person’s rights. The landmark First Amendment case, National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, is instructive. The plaintiffs, American Nazis planning a parade through a neighborhood populated by Holocaust survivors in Illinois, sued on First Amendment grounds when the local government tried to prevent them from carrying swastikas. The Supreme Court eventually ruled in favor of the Nazis because the First Amendment protects peaceful demonstrations with no regard for the vile or hateful content of the ideas being promoted […]

In his new book The Human City, Joel Kotkin tries to use NIMBYism as an argument against urbanism. He cites numerous examples of NIMBYism in wealthy city neighborhoods, and suggests that these examples rebut “the largely unsupported notion that ever more people want to move ‘back to the city’.” This argument is nonsense for two reasons. First, the NIMBYs themselves clearly want city life and a certain level of density–otherwise they would have moved to suburbia. In cities like Los Angeles and New York, a wide range of housing choices exist for those who can afford them. Second, the fact that some people want to prohibit new housing does not show that there is no demand for new housing. To draw an analogy: the War on Drugs prohibits many drugs. Does that mean that there is no demand for drugs? Of course not. If anything, it proves that there is lots of demand for drugs; otherwise government would not bother to prohibit it. For my more in-depth review of The Human City, read: Joel Kotkin’s New Book Lays Out His Sprawling Vision For America

In a recent piece published by 48hills, former Berkeley planning commissioner Zelda Bronstein takes aim at…well…too many things for me to succinctly recount in detail. So instead of attempting to respond to every single argument littered throughout her 7,000 word article, I’ll focus on the big stuff. Supply and demand: it’s a thing…we promise Ms. Bronstein asserts that supply and demand is, in fact, not a thing. Or at least if it is, it doesn’t apply to the Bay Area housing market. She writes that in California generally and the San Francisco Bay Area specifically, …the textbook theory of supply-and-demand—prices fall as supply increases—doesn’t apply. I’m unsure why Ms. Bronstein thinks the laws of supply and demand (ceteris paribus) don’t work here, but they’ve certainly been in force in Tokyo. Japan’s capital has seen sustained population growth as well as productivity increases over the last couple decades. And after twenty years of allowing housing to be built when and where people demand it, prices have remained gloriously flat. Just as expected. And when we look at American cities with the most supply elastic housing markets, we see a strong relationship between the ease with which new market rate construction can be developed and lower price increases overall. Unsurprisingly, San Francisco has one of the least elastic housing markets in the country and has experienced some of the most extreme percentage increases in housing prices as a result. No matter what example we look at or how we cut up the data, there’s nothing out there to contradict the basic YIMBY story about supply, demand, and price. Unless, of course, you don’t actually understand the story, which may be the problem in Ms. Bronstein’s case. For her benefit, I’ll restate the general position. More supply equals lower prices (in the aggregate and over time) The pro-supply […]

Recently Stephen Eide, writing in City Journal, argued that states could run cities better than cities can run themselves, by offering an antidote to the mismanagement gripping many localities (“Caesarism for Cities:, March 2016). In the process, he overlooked the nefarious nature of many state governments, and the way in which they already inhibit cities. Eide begins his article with a litany of urban issues: excessive debt, unfunded pensions and political dysfunction. “Local political apathy has enabled some cities to become dominated by one party or even one interest group, skewing the political process and often encouraging extensive corruption and mismanagement of finances…Fans of local autonomy are hard-pressed to explain these and other failures.” This was a flimsy premise, since everything he wrote could be applied to states themselves. In fact, the very magazine he was writing for routinely publishes articles decrying and detailing the excessive spending, debt, political dysfunction and unfunded pension crises of states like California, Illinois, Rhode Island and New York. Yet it is unlikely that we will see a piece advocating for the federal government to rein in state spending. “It makes more sense for state, not city, officials to do what’s right when faced with local fiscal distress instead of what’s politically convenient,” Eide wrote, offering no support for this faith in state officials. In fact, states have shown little willingness to engage in fiscal restraint. The Texas Department of Transportation recently spent over a billion dollars to relieve congestion on the Katy Expressway near Houston by widening it, thus subsidizing sprawl and inducing further demand. California’s unfunded gold-plated pensions equal around $600 billion, according to Eide’s very own City Journal. Similar tales of irresponsible spending can be found in virtually every state. It’s worth considering how urban fiscal problems are exacerbated by state interference. Many […]