Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Philadelphia Housing Authority will seize nearly 1,300 properties for a major urban renewal project in the city’s Sharswood neighborhood. The plan includes the demolition of two of the neighborhood’s three high-rise public housing buildings — the Blumberg towers — that will be replaced with a large mixed-income development. The new buildings will increase the neighborhood population tenfold with the majority of the new units to be affordable housing. The majority of the 1,300 lots slated for eminent domain are currently vacant. At a City Council hearing on Tuesday, Philadelphia Housing Authority CEO Kelvin Jeremiah testified that the redevelopment plan furthers the agency’s efforts to replace high-rise housing projects with lower-density units. However, PHA’s plan misses the forest for the trees. The benefits of demolishing the two towers are immediately undone by creating an entire neighborhood of public housing, effectively increasing the concentration of poverty in Sharswood. Adam Lang has lived in Sharswood for 10 years, and he posted about the plan in the Market Urbanism Facebook group. Adam has raised concerns that the PHA does not have an accurate number of how many of the 1,300 properties in the redevelopment territory are currently occupied. Adam’s primary residence is not under threat of eminent domain, however he owns four lots that are. He uses two lots adjacent to his home as his yard. The other two are a shell and a vacant lot. He purchased them, ironically, from the city with the plan to turn them into rentals. Adam’s concern about the inaccuracy of PHA’s vacancy statistics stem from the method that PHA employees used to create their estimate: driving by homes to see if they look occupied or not. Adam’s own property was on the list of vacants, and he said that he’s aware of other properties in the neighborhood […]

“How to Make an Attractive City”, a video by The School of Life, recently gained attention in social media. Well presented and pretty much aligned with today’s mainstream urbanism, the video earned plenty of shares and few critiques. This is probably the first critique you may read. The video is divided into six parts, each with ideas the author suggests are important to make an attractive city. I will cover each one of them separately and analyze the author’s conclusion in a final section. 1 – Not too chaotic, not too ordered The author argues that a city must establish simple rules to to give aesthetic order to a city without producing excessive uniformity. From Alain Bertaud’s and Paul Romer’s ideas, it can make sense to maintain a certain order of basic infrastructure planning in to enable more freedom to build in private lots. However, this is not the order to which the video refers, suggesting rules on the architectural form of buildings. The main premise behind this is that it “is what humans love”. But though the producers of the video certainly do love this kind of result, it is impossible to affirm that all humans love a certain type of urban aesthetics generated by an urbanist. It is even less convincing when this rule will impact density by restricting built area of a certain lot of land or even raising building costs, two probable consequences of this kind of policy: a specific kind of beauty does not come for free. Jane Jacobs, one of the most celebrated and influential urbanists of the modern era, clearly argued that “To approach a city, or even a city neighborhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, […]

Seamless Transit is the new transportation policy report from SPUR. Main author Ratna Amin proposes integrating the Bay Area’s balkanized transit systems to improve lackluster ridership. Given that the region has 23 separate transit providers–more than any other metropolitan area in the country–she may have a point. The report proposes standardizing service maps, fare structures, and payment systems; eliminating inter-system coverage gaps as well as redundant coverage; and reforming transit governance so that the different agencies actually make plans together instead of working at cross-purposes or not at all. The recommendations are sound and the report includes historical footnotes for context. These are helpful for understanding region’s complicated institutional arrangements. Seamless Transit is a fine piece of work and well worth the read for anyone interested in Bay Area transportation. But while organizational efficiency is important, it’s not the only thing to discuss. If we want to improve the region’s mass transit systems, we have to consider the physical environment in which those systems are embedded. To get transit right, the region needs to embrace density. Denser development around transit nodes would increase ridership substantially. When people live, work, and play in smaller geographic areas, more people travel between a fewer number of points. Mass transit, especially fixed rail transit, becomes more effective the denser development becomes. Hong Kong’s Metro Transit Railway (MTR) might be the quintessential example of urban density begetting mass transit success. The city is home to over 7 million inhabitants. It has a population density of over 18,000 residents per square mile. And of this population, 41% live within a half mile of an MTR station. The result? The MTR has a farebox recovery ratio of 186%–the highest in the world. Because of legal as well as political differences between Hong Kong and the Bay Area, […]

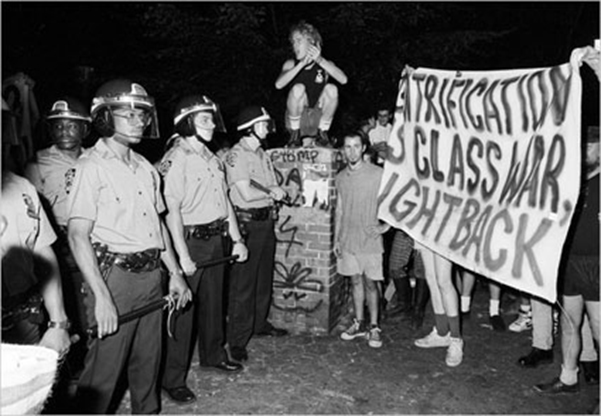

Gentrification is the result of powerful economic forces. Those who misunderstand the nature of the economic forces at play, risk misdirecting those forces. Misdirection can exasperate city-wide displacement. Before discussing solutions to fighting gentrification, it is important to accept that gentrification is one symptom of a larger problem. Anti-capitalists often portray gentrification as class war. Often, they paint the archetypal greedy developer as the culprit. As asserted in jacobin magazine: Gentrification has always been a top-down affair, not a spontaneous hipster influx, orchestrated by the real estate developers and investors who pull the strings of city policy, with individual home-buyers deployed in mopping up operations. Is Gentrification a Class War? In a way, yes. But the typical class analysis mistakes the symptom for the cause. The finger gets pointed at the wrong rich people. There is no grand conspiracy concocted by real estate developers, though it’s not surprising it seems that way. Real estate developers would be happy to build in already expensive neighborhoods. Here, demand is stable and predictable. They don’t for a simple reason: they are not allowed to. Take Chicago’s Lincoln Park for example. Daniel Hertz points out that the number of housing units in Lincoln Park actually decreased 4.1% since 2000. The neighborhood hasn’t allowed a single unit of affordable housing to be developed in 35 years. The affluent residents of Lincoln Park like their neighborhood the way it is, and have the political clout to keep it that way. Given that development projects are blocked in upper class neighborhoods, developers seek out alternatives. Here’s where “pulling the strings” is a viable strategy for developers. Politicians are far more willing to upzone working class neighborhoods. These communities are far less influential and have far fewer resources with which to fight back. Rich, entitled, white areas get down-zoned. Less-affluent, disempowered, minority […]

Co-authored with Anthony Ling, editor at Caos Planejado Gentrification Gentrification is the process through which real estate becomes more valuable and, therefore, more expensive. Rising prices displace older residents in favor of transplants with higher incomes. This shouldn’t be confused with the forced removal of citizens via eminent domain or “slum clearance.” Ejecting residents by official fiat is a different problem entirely. A classic example of gentrification is that of Greenwich Village, New York. Affluent residents initially occupied the neighborhood. It later became the city’s center for prostitution, prompting an upper-middle class exodus. Low prices and good location would later attract the textile industry. This was the neighborhood’s first wave of gentrification. But after a large factory fire, the neighborhood was once again abandoned. Failure, however, would give way to unexpected success: artists and galleries began to occupy the vacant factories. These old industrial spaces soon became home to one of the most important movements in modern art. In Greenwich Village, different populations came and went. And in the process they each made lasting contributions to New York’s economic and cultural heritage. This was only possible because change was allowed to take place. But change isn’t always easy. As a neighborhood becomes more popular, it also becomes more expensive. Tensions run high when long-time residents can’t afford rising rents. Some begin to call for rent controls or other measures to prevent demographic churn. But rent control is a temporary fix at best; in the longer term, its effects are negative. By reducing supply, rent control tends to drive up the cost of housing. And in the face of price controls, landlords may seek to exit the rental market entirely, further exacerbating any housing shortage. What, then, does this mean for urban development? How can cities evolve without completely displacing their middle and […]

Want to live in San Francisco? No problem, that’ll be $3,000 (a month)–but only if you act fast. In the last two years, the the cost of housing in San Francisco has increased 47% and shows no signs of stopping. Longtime residents find themselves priced out of town, the most vulnerable of whom end up as far away as Stockton. Some blame techie transplants. After all, every new arrival drives up the rent that much more. And many tech workers command wages that are well above the non-tech average. But labelling the problem a zero sum class struggle is both inaccurate and unproductive. The real problem is an emasculated housing market unable to absorb the new arrivals without shedding older residents. The only solution is to take supply off its leash and finally let it chase after demand. Strangling Supply From 2010 to 2013, San Francisco’s population increased by 32,000 residents. For the same period of time, the city’s housing stock increased by roughly 4,500 units. Why isn’t growth in housing keeping pace with growth in population? It’s not allowed to. San Francisco uses what’s known as discretionary permitting. Even if a project meets all the relevant land use regulations, the Permitting Department can mandate modifications “in the public interest”. There’s also a six month review process during which neighbors can contest the permit based on an entitlement or environmental concern. Neighbors can also file a CEQA lawsuit in state court or even put a project on the ballot for an up or down vote. This process is heavily weighted against new construction. It limits how quickly the housing stock can grow. And as a result, when demand skyrockets so do prices. To remedy this, San Francisco should move from discretionary to as-of-right permitting. In an as-of-right system, it’s much […]

I noticed an interestingly ironic thing today. The usual argument for the necessity of use-based zoning is that it protects homeowners in residential area from uses that would potentially create negative externalities – ie: smelting factory, garbage dump, or Sriracha factory. Urban Economics teaches us that such an event happening is highly unlikely in today’s marketplace. (nevermind the fact that nuisance laws should resolve these disputes) The business owner who is looking for a site for a stinky business would be foolish to look in a residential area where land costs are significantly higher. However, as Aaron Renn pointed out in the comments of my last post on Planned Manufacturing Districts, the inverse of this is happening in many cities as residential uses begin to outbid other uses in industrial areas: I think part of the rationale in this is that once you allow residential into a manufacturing zone, the new residents will start issuing loud complaints about the byproducts of manufacturing: noise, smells, etc. I know owners of businesses in Chicago who have experienced just that. They’ve been there for decades but now are getting complaints from people who live in residential buildings that didn’t even exist when the manufacturer located there. This puts those businesses under a lot of pressure to leave as officials will almost always side with residents who vote rather than businesses who don’t get to. It’s clear this is a more relevant defense of use-based zoning than the one we usually hear. Of course, I’d argue that segregating uses through zoning isn’t a just way to resolve these disputes, and my last post discusses some of the detrimental consequences for cities. It seems ironic, because it inverts the usual argument in-favor of zoning. Residents are choosing to move near established industrial firms, and PMDs are a tool […]

They are called different things in different cities, but they are similar in form and intent among the cities where they are found. For simplicity’s sake, a Planned Manufacturing District (PMD), as they are called in Chicago, is an area of land, defined by zoning, that prohibits residential development and other specific uses with the intent of fostering manufacturing and blue-collar employment. Proponent of PMDs purport to be champions of the middle-class or blue-collar workers, but fail to consider the unintended consequences of prohibiting alternative uses on that land. At best, PMDs have little effect on changing land-use patterns where industrial is already the highest-and-best-use. At worst, they have the long-run potential to distort the land use market, drive up the costs of housing, and prevent vibrant neighborhoods from emerging. A Race to The Bottom Before getting into it further, it is important to examine the economic decisions industrial firms make in comparison to other uses. Earlier in the industrial revolution, industry was heavily reliant on access to resources. Manufacturing and related firms were very sensitive to location. The firms desired locations with easy access to ports, waterways, and later railways to transport raw materials coming in, and products going out. However, the advent of the Interstate Highway System and ubiquitously socialized transportation network have made logistical costs negligible compared to other costs. Where firms once competed for locations with access to logistical hubs and outbid other uses for land near waterways in cities, they now seek locations with the cheapest land where they can have a large, single-floor facility under one roof. This means sizable subsidies must be combined with the artificially cheap land to attract and retain industrial employers on constrained urban sites. Additionally, today’s economy has become much more talent-based rather than resource based, and patterns have shifted accordingly. In contrast to industrial, residential and office uses are […]

Affordable housing policies have a long history of hurting the very people they are said to help. Past decades’ practices of building Corbusian public housing that concentrates low-income people in environments that support crime or pursuing “slum clearance” to eliminate housing deemed to be substandard have largely been abandoned by housing affordability advocates for the obvious harm that they cause stated beneficiaries. While rent control remains an important feature of the housing market in New York and San Francisco, even Bill de Blasio’s deputy mayor acknowledges the negative consequences of strong rent control policies. In the U.S. and abroad, politicians and pundits are beginning to vocalize the fact that maintaining and improving housing affordability requires housing supply to increase in response to demand increases. While support for older housing affordability policies has dissipated, the same isn’t true of inclusionary zoning. From New York to California, housing affordability advocates tout IZ as a cornerstone of successful housing policy. IZ has emerged as the affordable housing policy of choice because it has the benefit of supporting socioeconomic diversity, and its costs are opaque and dispersed over many people. However, IZ has several key downsides including these hidden costs and a failure to meaningfully address housing affordability for a significant number of people. Shaila Dewan of the New York Times captures the strangeness of IZ’s popularity: New York needs more than 300,000 units by 2030. By contrast, inclusionary zoning, a celebrated policy solution that requires developers to set aside units for working and low-income families, has created a measly 2,800 affordable apartments in New York since 2005. Montgomery County, a Maryland suburb of DC, has perhaps the most well-established IZ policy in the country. After 30 years, the program has produced about 13,000 units. Montgomery County is home to over one million people, 20 percent of whom have a household income of less than $43,000 annually. While this is an extraordinarily high income distribution relative to the rest of the country, this makes the […]

At Cato At Liberty, Randall O’Toole provides a list of recommendations for reversing Rust Belt urban decline in response to a study on the topic from the Lincoln Land Institute. He focuses on policies to improve public service provision and deregulation, but he also makes a surprising recommendation that declining cities should “reduce crime by doing things like changing the gridded city streets that planners love into cul de sacs so that criminals have fewer escape routes.” This recommendation is surprising because it would require significant tax payer resources, a critique O’Toole holds against those from the Lincoln Land Institute. Short of building large barricades, it’s inconceivable how a city with an existing grid of streets would even go about turning its grid into culs de sac without extensive use of eminent domain and other disruptive policies. O’Toole is correct that the grid owes its origins to authoritarian regimes and that today it’s embraced by city planners in the Smart Growth and New Urbanist schools. But while culs de sac may have originally appeared in organically developed networks of streets, today’s culs de sac promoted by traffic engineers are hardly a free market outcome. As Daniel Nairn has written, the public maintenance of what are essentially shared driveways “smacks of socialism in its most extreme form.” Some studies have found that culs de sac experience less crime relative to nearby through streets, perhaps in part because they draw less traffic. However, it’s far from clear that a pattern of suburban streets makes a city safer than it would be would be with greater street connectivity. Some studies find that street connectivity correlates with greater social capital. O’Toole’s promotion of social engineering through culs de sac to create a localized drop in crime at the expense of a city’s residents’ social capital is […]