Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Caos Planejado, in conjunction with Editora BEI/ArqFuturo, recently published A Guide to Urban Development (Guia de Gestão Urbana) by Anthony Ling. The book offers best practices for urban design and although it was written for a Brazilian audience, many of its recommendations have universal applicability. For the time being, the book is only available in Portuguese, but after giving it a read through, I decided it deserved an english language review all the same. The following are some of the key ideas and recommendations. I hope you enjoy. GGU sets the stage with a broad overview of the challenges facing Brazilian cities. Rapid urbanization has put pressure on housing prices in the highest productivity areas of the fastest growing cities and car centric transportation systems are unable to scale along with the pace of urban growth. After setting the stage, GGU splits into two sections. The first makes recommendations for the regulation of private spaces, the second for the development and administration of public areas. Reforming Regulation Section one will be familiar territory for any regular MU reader. GGU advocates for letting uses intermingle wherever individuals think is best. Criticism of minimum parking requirements gets its own chapter. And there’s a section a piece dedicated to streamlining permitting processes and abolishing height limits. One interesting idea is a proposal to let developers pay municipalities for the right to reduce FAR restrictions. This would allow a wider range of uses to be priced into property values and create the institutional incentives to gradually allow more intensive use of land over time. Meeting People Where They Are Particular to the Brazilian experience is a section dedicated to formalizing informal settlements, or favelas. These communities are found in every major urban center in the country and often face persistent, intergenerational poverty along with […]

In new research on parking policy in the Journal of Economic Geography, Jan Brueckner and Sofia Franco argue that residential developers should be required to provide more off-street parking in places where street parking contributes to traffic congestion. They argue that because traffic congestion is a negative externality, off-street parking requirements improve urban living. But street parking only contributes to traffic congestion when policymakers underprice it. Rather than addressing the externality of a government-created problem with new regulations, cities should price their street parking appropriately. Brueckner and Franco’s argument relies on the assumption that off-street parking will be under-provided without government intervention. They argue that because drivers circle their destination looking for free or cheap street parking, minimum parking requirements make people better off. The authors are correct in arguing that street parking contributes to the problem of traffic congestions. Parking guru Donald Shoup estimates that drivers who are circling around looking for parking spots make up 30 percent of downtown traffic. Cruising for parking imposes an external cost on others by causing everyone to waste time in slow traffic. While, Brueckner and Franco actually cite Shoup’s work on street parking and traffic congestion, they ignore his insight that when parking is priced appropriately, cities can eliminate this externality. The incentive to cruise for parking originates with public policy when city officials provide street parking at below-market prices. When parking prices are high enough, drivers will leave some parking availability on each block, eliminating the cruising problem without the need for minimum parking requirements. San Francisco’s SFPark program provides an example of successful implementation of variable pricing based on demand. SFPark has the goal of maintaining one to two available spots on each block so that drivers don’t contribute to traffic congestion while they’re looking for parking. When street parking is priced high […]

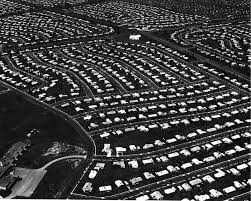

It is because every individual knows little and, in particular, because we rarely know which of us knows best that we trust the independent and competitive efforts of many to induce the emergence of what we shall want when we see it. — Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty Imagine the perfect city. If you have a clear picture in mind, you’re not alone. Tsars, emperors, and prophets have been trying to build perfect cities for millennia. With the emergence of the field of urban planning and modern social science, everyone from stenographers to industrialists to independent architects have joined in. For Ebenezer Howard, the perfect city was the Garden City, a corporate-owned residential satellite on the outer edge of town. For Le Corbusier, it was the Ville Radieuse, full of “skyscrapers in the park” and elevated highways. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was Broadacre City, a dispersed anti-city full of single-family homes on one-acre lots. Each reflects a distinct vision of urban life, and each seems to have as many opponents as it does proponents. Thankfully, few of these plans have ever been implemented in full on a mass scale. Yet “perfect city” thinking—the view that one particular vision of urban form should be imposed by planners—has manifested itself in small ways in cities around the world through the construction and enforcement of specific theories of how a city should work. This approach to urban form involves expanding urban planning beyond prudentially managing infrastructure and mitigating destructive negative externalities and toward enforcing and preserving particular lifestyle and aesthetic preferences. Consider: while Ville Radieuse was never built, many cities bulldozed traditional urban neighborhoods to construct the urban elevated highways of Le Corbusier’s dreams. While Broadacre City never moved beyond the model stage, many suburban communities still zone minimum lot sizes […]

[This piece was originally published on the site Better Institutions.] On March 7th, Los Angeles is going to vote on the type of city it wants to be. The vote will be over Measure S, formerly known as the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative (NII), which seeks to limit housing development in the city. Backers of the initiative claim that City Council is too beholden to developers, and that the pace of new housing and commercial development in the city is out of control. They also express concern that “mega projects” are making Los Angeles less affordable, since few new homes are being targeted at low and moderate income households. It’s a really bad plan, but calling Measure S “bad” doesn’t go nearly far enough. It is, in fact, the Donald Trump of ballot initiatives. It’s a cynical effort to co-opt a legitimate sense of frustration—frustration felt by those who haven’t shared in the gains of an increasingly bifurcated society—and to use that rage and desperation for purely selfish purposes. It invites us to vent our frustrations and, in so doing, to further enrich those who helped to engineer our ill fortune. And as with Trump, a Measure S victory will roll back the clock on years of steady progress. Since I think there are a lot of folks out there who genuinely haven’t made up their minds about the initiative, or aren’t yet familiar with it, I’d like to summarize some of the most important reasons to oppose it when it comes time to vote this March. 1. IT WILL MEAN FEWER AFFORDABLE HOUSING UNITS FOR LOW INCOME HOUSEHOLDS. The Coalition to Preserve LA, which is backing the initiative, is turning this into a referendum on housing development in Los Angeles. They’re arguing that new homes have “wiped out thousands of […]

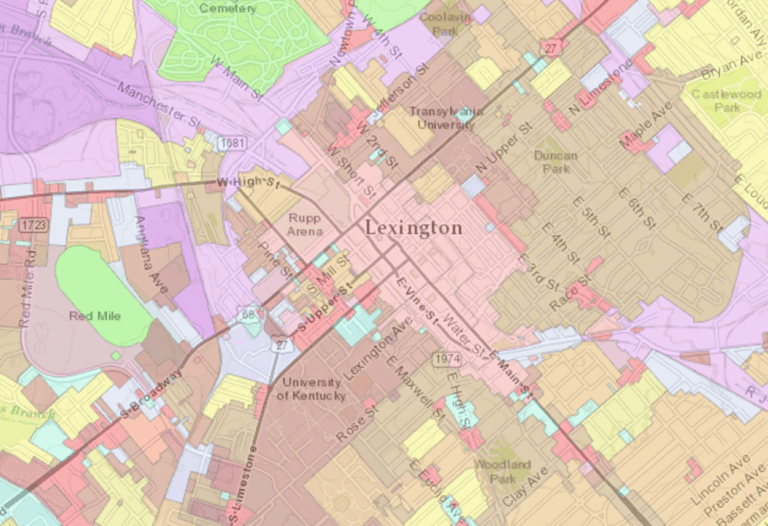

Lexington, Kentucky is a wonderful place, and that’s getting to be a problem. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the city: its urban amenities, thriving information economy, and unique local culture have brought in throngs of economic migrants from locales as exotic as Appalachia, Mexico, and the Rust Belt. The problem, rather, is that the city isn’t zoned to support this newfound attention. Over the past five years, the city has grown by an estimated 18,000 residents, putting Lexington’s population at approximately 314,488. Lexington has nearly tripled in size since 1970 and the trend shows no signs of stopping, with an estimated 100,000 new residents arriving by 2030. Despite this growth, new development has largely lagged behind: despite the boom in new residents, the city has only permitted the construction of 6,021 new housing units over the past five years—not an awful ratio when compared to a San Francisco, but still putting us firmly on the path toward shortages. The lion’s share of this new development has taken the form of new single-family houses on the periphery of town. Create your own infographics. Sources: ACS/Census Bureau At the risk of sounding like a broken record, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with single-family housing on the periphery of town. Yet in the case of Lexington, it’s suspect as a sustainable source of affordable housing. Lexington was the first American city to adopt an urban growth boundary (UGB), a now popular land-use regulation that limits outward urban expansion. As originally conceived, the UGB program isn’t such a bad idea: the city would simultaneously preserve nearby farmland and natural areas (especially important for Lexington, given our idyllic surrounding countryside) while easing restrictions on infill development. Create your own infographics. Source: Census Bureau The trouble with Lexington is that the city has undertaken […]

Planners, like all professions, have their own useful mythologies. A popular one goes something like this: “Many years ago, us planners did naughty things. We pushed around the poor, demolished minority neighborhoods, and forced gentrification. But that’s all over today. Now we protect the disadvantaged against the vagaries of the unrestrained market.” The seasoned—which is to say, cynical—planner may knowingly roll her eyes at this story, but for the true believer, this story holds spiritual significance. By doing right today, the reasoning goes, planners are undoing the horrors of yesterday. This raises the question: are planners doing right today? That’s not at all clear. Just ask Hinga Mbogo. After emigrating from Kenya, Mr. Mbogo opened Hinga’s Automotive in East Dallas in 1986. Mr. Mbogo’s modest business is precisely the kind of thing cities need, providing a service for the community, taxes for the city, and blue-collar jobs. While perhaps not of the “creative class,” Mr. Mbogo and his small business represent the type of creative little plan that cities cultivate and depend on. Hinga’s Automotive has thrived for 19 years and looked primed for another 19. Unfortunately for Mr. Mbogo, Dallas planners had other plans. In 2005, the city rezoned the area to prohibit auto-related businesses. While rezonings—particularly upzonings—aren’t necessarily a bad thing, Dallas planners opted to force their vision through and implemented a controversial planning technique known as “amortization.” Normally when planners rezone an area, they allow existing uses that run afoul of the new code to continue operating indefinitely. These are known as “non-conforming uses” and they’re common in neighborhoods across the country, often taking the form of neighborhood groceries, restaurants, and small industrial shops. Yet under amortization, the government forces non-conforming uses to cease operating without any compensation. In the case of Hinga’s Automotive, this means […]

Sometimes, prosperity is an illusion. The massive building boom in the People’s Republic of China is creating outer signs of affluence, but there isn’t enough demand to put residents in the new homes. As in many similar urban projects across the country, the Chinese government has been pouring billions of dollars into Gansu Province to build a new city called Lanzhou New Area. The Washington Post reports, This city is supposed to be the “diamond” on China’s Silk Road Economic Belt — a new metropolis carved out of the mountains in the country’s arid northwest. But it is shaping up to be fool’s gold, a ghost city in the making. Lanzhou New Area, in Gansu province, embodies China’s twin dreams of catapulting its poorer western regions into the economic mainstream through an orgy of infrastructure spending and cementing its place at the heart of Asia through a revival of the ancient Silk Road. Hundreds of hills on the dry, sandy Loess Plateau were flattened by bulldozers to create the 315-square-mile city. But today, cranes stand idle in planned industrial parks while newly built residential blocks loom empty. Streets are mostly deserted. Life-size replicas of the Parthenon and the Sphinx sit surrounded by wasteland, monuments to profligacy. Spontaneous Cities China’s central planners haven’t even begun to appreciate, let alone practice, the lessons of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs, who viewed cities and the socioeconomic processes that go on in them as largely the result of spontaneous, unplanned entrepreneurial development. As an economist quoted in the Washington Post article points out, Urbanization and modernization are processes that naturally take place.… You can’t force it to happen or have 1,000 places copy the same model. Construction of these so-called ghost cities is likely financed by artificial credit expansion. In other words, people […]

Urban Institute Press • 2005 • 494 pages • $32.50 paperback In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Nelson argues that while all levels of American government have been expanding since World War II, people have responded with a spontaneous and massive movement toward local governance. This has taken two main forms. The first is what he calls the “privatization of municipal zoning,” in which city zoning boards grant changes or exemptions to developers in exchange for cash payments or infrastructure improvements. “Zoning has steadily evolved in practice toward a collective private property right. Many municipalities now make zoning a saleable item by imposing large fees for approving zoning changes,” Nelson writes. In one sense, of course, this is simply developers openly buying back property rights that government had previously taken from the free market, and “privatization” may be the wrong word for it. For Nelson, however, it is superior to rigid land-use controls that would prevent investors from using property in the most productive way. Following Ronald Coase, Nelson evidently believes it is more important that a tradable property right exists than who owns it initially. The second spontaneous force toward local governance has been the expansion of private neighborhood associations and the like. According to the author, “By 2004, 18 percent—about 52 million Americans—lived in housing within a homeowner’s association, a condominium, or a cooperative, and very often these private communities were of neighborhood size.” Nelson views both as positive developments on the whole. They are, he argues, a manifestation of a growing disenchantment with the “scientific management” of […]

My guest this week is Anthony Ling. Anthony is founder and editor of Caos Planejado, a Brazilian website on cities and urban planning. He also founded Bora, a transportation technology startup and is currently an MBA candidate at Stanford University. He graduated Architecture and Urban Planning at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and worked with Isay Weinfeld early in his career. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Be sure to check out Caos Planejado. Whether Portuguese is your native language or you’re interested in Brazilian urban planning issues, it’s a fantastic resource. Learn more about the emergent order of informal favela development. Everyone interested in urban planning should, at the very lease, read the Wikipedia article on Brasilia. Learn more about on-demand transit. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

This book review is part of a TLC Book Tour. The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life by Jonathan F. P. Rose In The Well-Tempered City, real estate developer Jonathan F. P. Rose offers a sweeping history of cities and equally grandiose policy proposals to improve urban outcomes. In the vein of Jane Jacobs and F.A. Hayek, Rose identifies that cities are “wicked” problems rather than engineering problems that policymakers can solve through tinkering. In spite of this recognition of the complexity of cities’ interrelated systems, Rose asserts that cities need visionaries to address problems from obesity to climate change from the top down. Rose leads with the most interesting section of his book on the origins of early cities. In support of his theory that great cities are built by visionaries, he focuses on ancient cities that were founded around religious sites, including Uruk and Teotihuacan, downplaying the path of great cities emerged organically from trading posts, like Venice or Rotterdam. He advocates for the benefits of orderly urban layouts like Hippodamian plan or the magic square that ancient Chinese cities followed. A theme running throughout the book is that American urban planning has embraced the Western values of individualism and free will while giving short shrift to the Eastern value of harmony, such as the unification that comes from top-down urban design. In support of more cohesive plans, Rose downplays the incredible progress that has been possible through decentralized urban and economic development. Throughout the book, Rose argues that American cities are suffering from a lack of vision from their planners. Unlike ancient leaders who built grand temples and imposing walls, today’s planners focus on enforcing rules rather than defining a city’s aesthetics. He writes: It turns out that a city can pick any […]