Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Tyler is stirring the pot over at Marginal Revolution, asking whether Tokyo’s low rents are a YIMBY success or just a productivity failure: low productivity and low immigration keep demand down. He calls the latter “NIMBYism”. That framing doesn’t hold up very well, but we can discard it and think about the substance of the question. If we were totally ignorant of policy, what would we expect? Alonso-Muth-Mills models say prices should be higher in larger cities, and Tokyo is the largest city in the world. Most people think that price/income is the right way to compare home prices across countries, although price/construction cost might be better if we could accurately measure the latter. Let’s at least clarify the factual issues. Are Tokyo wages low? Japan wages are quite low by developed-world standards. Tokyo is perhaps 22% above the national average, about half of the New York/USA markup. The Alonso-Muth-Mills model says the largest city should be so because its wages are highest. Obviously, that assumes free movement of people. It’s not a mystery why Karachi is larger than Austin. But then why is Tyler criticizing Japan for low immigration? Clearly Japanese people should emigrate, like wage peer Spaniards and Poles. Is Tokyo cheap? Only relatively. I asked ChatGPT for a comparative list, but it wouldn’t even try. The best comparison I could find was in Demographia’s affordability yearbooks. They last included Japan in 2018 because of data reliability issues, so ymmv. But a Japanese PDFsays that Metropolitan Tokyo’s price-income ratio was 7.16 in 2016; in Tokyo Prefecture (the core) it was 9. Who knows how the definitions differ? All sources agree that Japanese home prices have risen less than most of the world in the pandemic era, so current data would favor Tokyo more. Tyler’s claim that Japan’s “brand […]

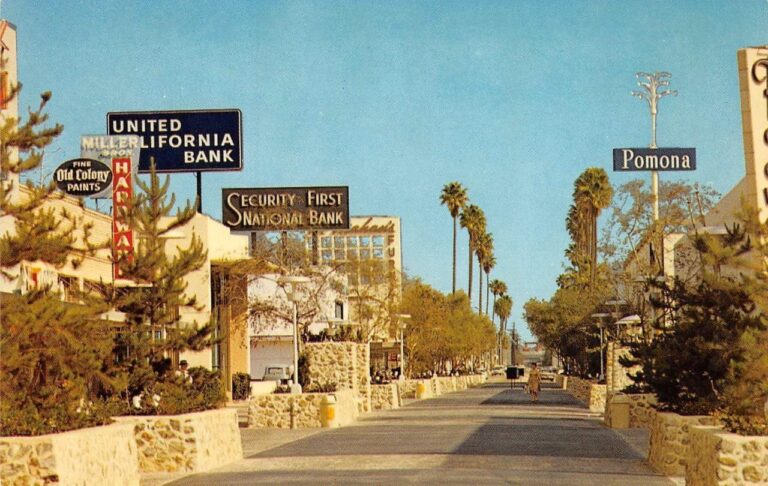

Urbanists love to celebrate, and replicate great urban spaces – and sometimes can’t understand why governments don’t: But what’s important to recall – especially for those of us under, uh, 41 – is that pedestrianized streets aren’t a new concept coming into style, they’re an old one that’s been in a three-decade decline. Samantha Matuke, Stephan Schmidt, and Wenzheng Li tracked the rise and decline of the pedestrian mall up to the onset of the pandemic. Even in the urbanizing 2000s and 2010s, 14 pedestrian malls were “demalled” against 4 streets that were pedestrianized: In a 1977 handbook promoting pedestrianization, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo admit that some of the earliest “successes” had already failed: In Pomona, California, the first year [1962] the mall received nationwide press coverage as a successful model of urban revitalization; there was a 40 percent increase in sales. But the mall was slowly abandoned by its patrons, and now, after fifteen years of operation, it is almost totally deserted. A Handbook for Pedestrian Action, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo, p. 25 One obvious reason for the failure of many other pedestrianized streets is that they were too little, too late. The pedestrian mall was one of several strategies against the overwhelming ebb tide of retail from downtowns in the postwar era. They weren’t seen as alternatives to driving, but destinations for drivers, who could park in the new, convenient downtown lots that replaced dangerous, defunct factories. A minority of the postwar-era malls survived. The predictors of survival are sort of obvious in hindsight: tourism, sunny weather, and lots of college students, among other things. Some of the streets which were “malled” and “demalled” have rebounded nicely in the 2000s. The slideshow below shows Sioux Falls’ Phillips Avenue in 1905, 1934, c. 1975, and 2015. The […]

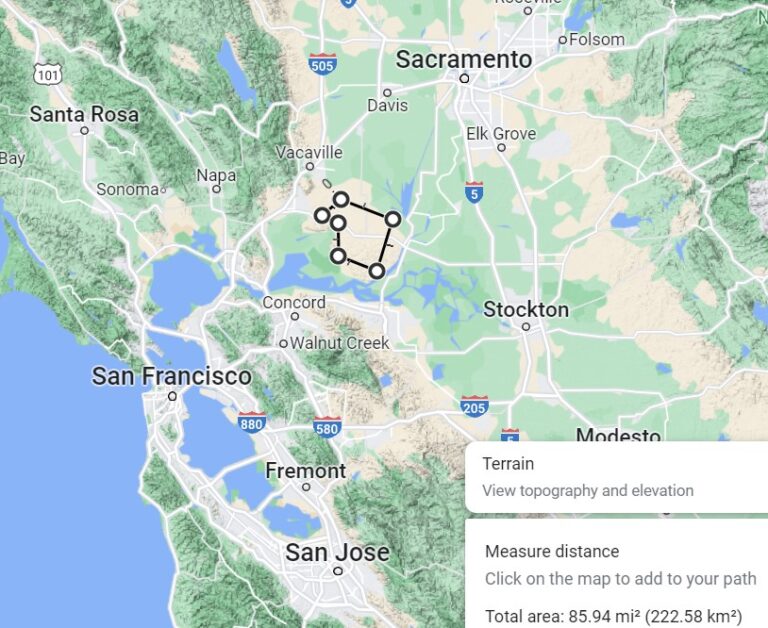

Conor Dougherty and Erin Griffith revealed the identities behind a Silicon Valley investor group, Flannery Associates, that had gradually purchased 55,000 acres of ranchland near Travis Air Force Base in Solano County, California. Scale check: that’s a lot of land. San Francisco is 30,000 acres; San Jose is 116,000. Earlier WSJ reporting includes a map of Flannery’s holdings, which are predictably a bit scattered. To zoom out and give a scale comparison, I outlined a 55,000 acre contiguous blob around the core of the Flannery holdings. At the density of nearby Vacaville, this much land would be home to nearly 300,000 people. If it matched Oakland, it would be more than twice that. Many, especially at the Charter Cities Institute, have written about new cities. But can a new city ever be truly “market urbanist”? Or is the intent to create a city necessarily an exercise in centralized planning? Monopoly Bizarrely, the one actor who could most purely create a market-driven city is the government: It could use eminent domain to assemble only the land needed for new infrastructure, tax all landowners fairly, and allow competition among landowners to compete via development and land use. At the opposite extreme, when a profit-maximizing private actor owns all the land, it faces a unique form of the monopolist’s tradeoff: The longer it holds onto land, the higher price it can charge on sale, but the less that land contributes to urban growth. One way to sidestep this tradeoff is for the monopolist to develop land itself. But of course that concentrates risk, and the cost of development is at least a hundred times more than the land cost (which appears to have averaged about $16,000 per acre in Solano County). Zero to one So what’s a mega-landowner to do? I’d start by […]

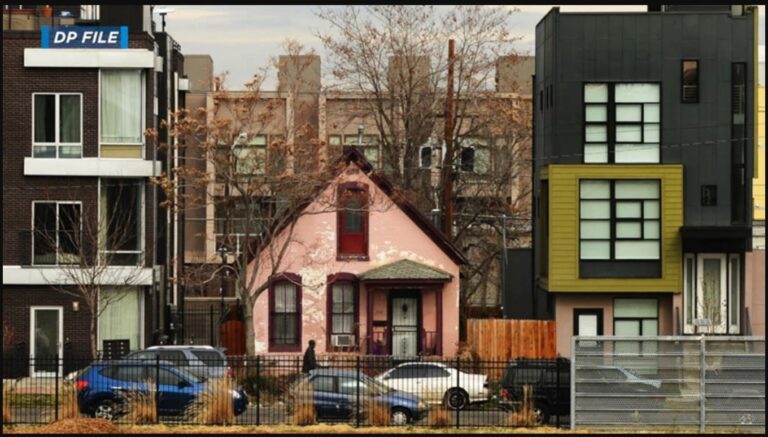

In many cities, poor people occupy valuable urban land close to downtown jobs, amenities, and transit. They can afford to live there because the housing stock in inner areas is usually older. If it hasn’t been completely renovated, the result can be quite cheap, even if the land is pretty valuable. In areas where there’s already some gentrification pressure, landlords face a timing problem: they can renovate (or sell to a developer) now, and cash out. Or they can hoard the property and wait until prices rise, supplying low-cost housing in the meantime. Land value taxes are specifically designed to penalize the hoard-and-wait approach by raising the annual tax cost of sitting on valuable land. It is specifically designed to accelerate neighborhood change. That’s the point. That’s what it says on the tin. Gentrification isn’t the only urban problem, and maybe it’s a small enough urban problem that a land value tax is a good idea anyway. But I think most of the benefits of Georgism can be unlocked with George-ish schemes (like renovation abatements or vacant land taxes) that are more narrowly designed.

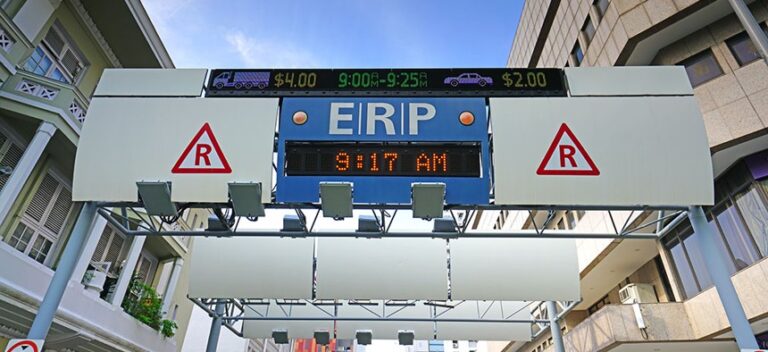

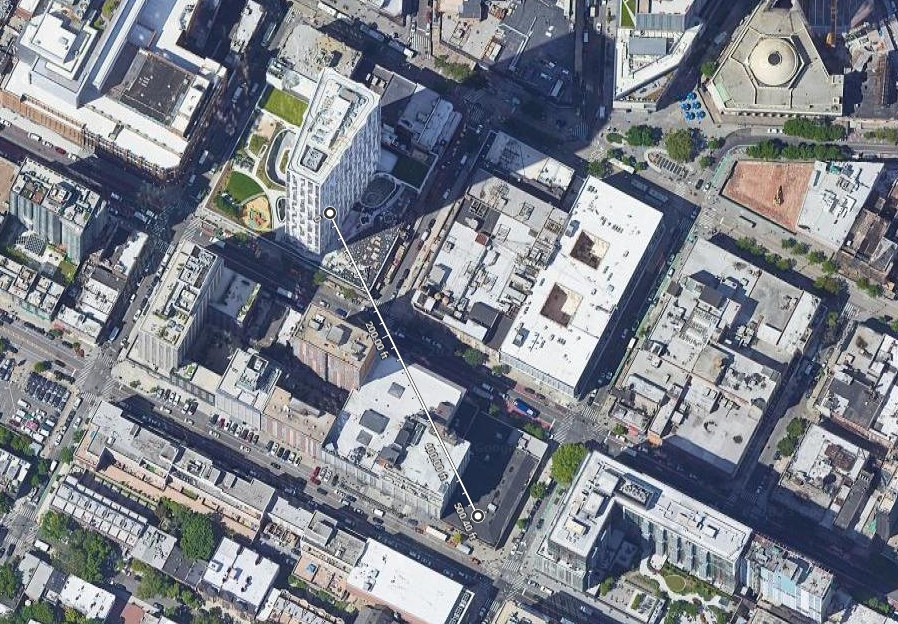

In a series of recent posts, Tyler Cowen has taken the view that congestion prices in major downtowns are a bad idea. This is what one might expect of a typical New Jerseyan, but not a typical economist. The writing in these posts is a bit squirrelly (or is it Straussian?), but as best I can make out, Tyler is deviating from the mainline economic views of externalities and prices by arguing a few points: Urban serendipity and growth are high-value externalities quite distinct from the usual efficiencies of combining large amounts of capital and labor in downtown office towers. Occasional visitors to the city find very high value there (presumably via a long-right-tail distribution) including by creating demand for new goods Congestion pricing will (a) decrease the number of people in the city, (b) particularly high-value visitors. He also makes some specific critiques of the mechanism design of the proposed NYC congestion charge. It’s worth getting that right, but let’s leave the technicalities aside here. Tyler’s points – as I’ve summarized (or mangled) them – seem like a mix of reasonable and wrong, although in several cases difficult if not impossible falsify. I’ll tackle these points in a completely irresponsible order. 2. Distinguished visitors On the second point: Diminishing marginal returns is enough to give Tyler’s argument the benefit of the doubt. The first visit to a symphony or subway likely has a bigger inspirational impact than the seventh or seven-hundredth. And outsiders may bring insights to the city in an Eli-Whitney-and-the-cotton-gin way. But for consuming new goods? Perhaps visitors’ demand is enough to sustain new imitations of low-end consumer goods (like a McDonalds in Chennai, if there is one). But for narratives of urban creativity, I prefer Malcolm Gladwell’s account of Airwalk shoes or Peter Thiel’s identification of […]

“Renting in Providence puts city councilors in precarious situations.” That was the Providence Journal’s leading headline a few days ago, as the legislature waited for Governor Daniel McKee to sign a pile of housing-related bills (Update: He signed them all). Rhode Island doesn’t have a superstar city to garner headlines, but it’s housing costs have mounted as growth has crawled to a standstill. But unlike in Montana and Washington, Rhode Island’s were largely procedural, aiming to lubricate the the gears of its existing institutions rather than directly preempting local regulations. House Speaker Joseph Shekarchi (D-Warwick), who championed the reforms, clearly drew on his professional expertise as a zoning attorney to identify areas for procedural streamlining. Specific and objective Six bills transmitted to the governor cover the general rules affecting most Rhode Island zoning procedures: S 1032 makes it easier to acquire discretionary development permission. Municipalities cannot enforce regulations that make it near-impossible to build on legacy lots that do not meet current regulatory standards. Municipalities can more quickly issue variances and modifications. (Rhode Island draws a unique distinction between minor and substantial variances, labeling the former “modifications” and subjecting them to a simpler process. A substantial variance must go before a board for approval; a modification can be approved administratively unless a neighbor objects. Municipalities must issue “specific and objective” criteria for “special use permits”, otherwise those use are automatically allowed as of right. That phrase – specific and objective – shows up again and again in Speaker Shekarchi’s bills. S 1033 requires that zoning be updated to match a municipality’s own Comprehensive Plan within 18 months of a new plan’s adoption. It also requires an annually updated “strategic plan” for each municipality, although the content and legal force of the strategic plans are unclear to me. S 1034 broadly […]

In a pair of posts, Scott Alexander goads his mostly-YIMBY readers by claiming to believe that density is likely to increase prices. To quantify his readers’ views, he laid out a thought experiment in a Google poll, the results of which we’ll no doubt see in a few days. You can see the poll – and my answer – below. As a YIMBY scholar, I mood-affiliate with the first answer, but I chose the middle one because there is a fundamental misunderstanding between pro-housing people like me and Scott’s recent posts. Housing growth is not the same as city densification Scott’s experiment isn’t a “housing growth” experiment, it’s a “city densification” experiment. Crucially, he requires “proportional increases in the number of office buildings, schools, etc”. That is, the experiment would increase office space at the same pace as housing even though office vacancy rates (19%) are far higher than housing vacancy rates (~1.7%). Oakland is a pretty balanced city: as best I can tell from simple Census data, it probably has a jobs/residents ratio pretty close to the California average (by contrast, San Francisco has twice the state jobs/resident ratio). If Scott ran his experiment in a bedroom community, or stipulated that office space is left under current regulations, I’d have an easy time coming down on the “less expensive” side of the ledger. The point of the YIMBY movement is that housing faces uniquely strict regulation. California cities (and those in some other states) believe that offices and industrial uses are “taxpayers”, generating more revenue than they use in services. Housing is viewed as a fiscal cost. Regulation (“fiscal zoning“) and discretionary decisions have reflected this bias for decades. The result is headlines like “SF added jobs eight times faster than housing since 2010.” If Oakland upzoned citywide, it […]

In a Maryland neighborhood. rent control caused condo conversions of 15 percent of multifamily buildings. The county council might inflict the same fate on the entire region.

I'm pre-disposed to find reasons to love Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern's book *Homelessness is a Housing Problem*. But the book moved my priors in the opposite direction than the authors intended.

Why are Max Holleran's book, Richard Schragger's law review article, and randos on Twitter all misinterpreting one important research article?