Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Global house prices have been out of control for quite some time. This has helped to reduce economic growth, increase unemployment and was even diagnosed as the greatest cause of inequality in the developed world in a 2016 paper by Matthew Rognlie. However, rents have failed to show the same turbulence (as shown below) – this has led some to question the common response that the crisis of house prices is caused by a supply shortage.

The most famous example of this argument is from Ian Mulheirn. He argues that the collapse in the mortgage interest rate since the 1990s, as well as growing demand from international investors, has made it easier to purchase property causing a rise in demand. To him, this is the biggest reason for the crisis.

However, simple price theory tells us that prices only rise when supply grows less than that rise in demand. Whilst lower interest rates have made it more affordable to buy houses, if supply were to rise simultaneously by the same amount then we should expect prices to remain stagnant. Indeed, we can observe this in history – after the Great Depression, Great Britain reduced interest rates massively. However, rather than causing a boom in prices they remained stagnant, due to an increase in housebuilding. Moreover, this is unhelpful from a policy perspective given increasing interest rates would risk higher unemployment. The argument is therefore unhelpful at best, and insufficient at worse in explaining why rents aren’t increasing as quickly as prices.

A recent paper published by the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE has sought a better explanation. Here, Christian Hilber and Andreas Mense argue that the price to rent ratio only increases with a demand shock where supply is sufficiently constrained. Indeed, they find that in Greater London, one of the most toxic areas to house building in the world, local labour demand shocks account for 63% of the increase in the price to rent ratio. So why do supply constraints affect house prices so much more than rental prices in superstar cities?

Since rental markets depend largely on short-term demand and supply, then the elasticity of this supply curve will determine the impacts of a demand shock on prices. This means that markets will experience higher rent inflation after a demand shock where housing supply is less elastic in the short run.

What they find is that short-run supply is a lot less elastic than the long run (which is a determinant of prices). This is because demand shocks lead investors to update their expectations of risk premiums and growth rates. Given rental markets will be determined more by the short-run than house purchasing markets this will have the effect of the impacts of a demand shock being less substantial.

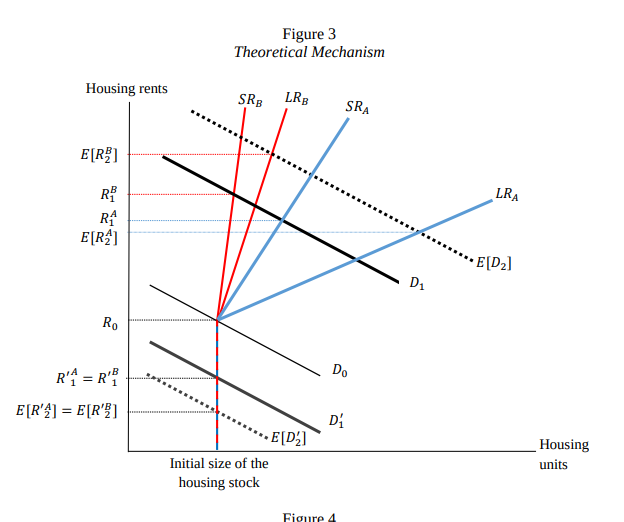

This can be explained through the diagram below:

The blue line represents location A and the red line location B. In location A supply (an area with less price constraints) is a lot more elastic. This is because there are less planning constraints to building more housing. The effect of this is that where housing rents increase in the short run the market can react leading to rents falling from RA1 to E(RA2).

However, in the less elastic market (representing a city with more planning constraints) supply does not react as substantially. This results in the demand shock (D1 to E(D2)) having a significant effect on prices rising from RB1 to E(RB2).

So, prices rising faster than rents, as Ian Mulheirn holds, doesn’t tell us that supply constraints are an improper diagnosis for the cause of our housing woes. Instead, it is the opposite. The main reason why this discrepancy exists is down to supply constraints.

Therefore, challenges to the conventional wisdom that higher house prices are down to supply constraints made through appeals to the price-rent ratio should be ignored. Instead, we should focus on increasing supply as a vehicle to help bring down both rental and buying costs of housing.