Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

walkable suburbs have as many children as more typical suburbs

Snowfall reveals a curiosity of the commons and - Alan Cole claims - something about the character of urban progressives.

Because there are no market signals that could identify the best and highest use of street space, it is the role of urban planners to allocate the use of street space between different users and to design boundaries between them where needed.

Cities have always invited us to be constantly on the move. We move around to get to work, go shopping, meet friends, attend a concert, visit an art exhibition, and take advantage of all the many activities that a metropolis offers.

Updated 1/11/24 to add 3 new papers, Wegmann, Baqai, and Conrad (2023), Dobbels & Tavakalov (2023), and Hamilton (2024). The original post was published 3/14/23. A concerted research effort has brought minimum lot sizes into focus as a key element in city zoning reform. Boise is looking at significant reforms. Auburn, Maine, and Helena, Montana, did away with minimums in some zones. And even state legislatures are putting a toe in the water: Bills enabling smaller lots have been introduced [in 2023] in Arizona, Massachusetts, Montana, New York, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. The bipartisan appeal of minimum lot size reform is reflected in Washington HB 1245, a lot-split bill carried by Rep. Andy Barkis (R-Chehalis). It passed the Democratic-dominated House of Representatives by a vote of 94-2 and has moved on to the Senate. City officials and legislators are, reasonably, going to have questions about the likely effects of minimum lot size reductions. Fortunately, one major American city has offered a laboratory for the political, economic, and planning questions that have to be answered to unlock the promise of minimum lot size reforms. Problem, we have a Houston Houston’s reduced minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet in 1998 (for the city’s central area) and 2013 (for outer areas). This reform is one of the most notable of our times – and thus has been studied in depth. For a summary treatment, see Emily Hamilton’s 2023 case study. To bring all the existing scholarship into one place, I’ve compiled this annotated bibliography covering the academic papers and some less-formal but informative articles that have studied Houston’s lot size reform. Please inform me of anything I’m missing – I’ll add it. Political economy of Houston’s reform M. Nolan Gray & Adam Millsap (2020). Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis […]

A study by Maxim Massenkoff and Nathan Wilmers argues that “low-price full-service restaurants,” like Olive Garden or the Cheesecake Factory, are the third places in which rich and poor are most likely to rub shoulders. Using location data, they found that these low-price chain restaurants had more class integration than churches, schools, and independent bars and restaurants. Although Massenkoff and Wilmers steer clear of making forceful policy recommendations, they do seem to caution policymakers in cities like San Francisco and New York City that have passed regulations to curb an overabundance of chains: Our results demonstrate that the places that contribute most to mixing by economic class are not civic spaces like churches or schools, but large, affordable chain restaurants and stores. Insofar as policy makers seek to increase exposure between different classes, they should pay attention to the role of firms in shaping class mixing. It is not necessarily surprising that chain restaurants tend to be places where people of all classes mix. The very design of these restaurants is meant to appeal to the widest audience possible. Behold your local Cheesecake Factory. It is usually found in suburban shopping centers where land is cheap, such that the Factories are large and capable of holding all large numbers of customers. And of course, The Factory’s famously tome-like menu, which has everything from hamburgers to orange chicken to shrimp scampi, betrays the chain’s intention to serve as many different walks of life as possible. But it is also worth considering that chains, even if they are designed to appeal to the largest audience possible, might be playing an outsized role in class integration. Research from City Observatory argues that chains tend to proliferate in more car-dependent cities. It is not entirely obvious why this is the case, but some theories […]

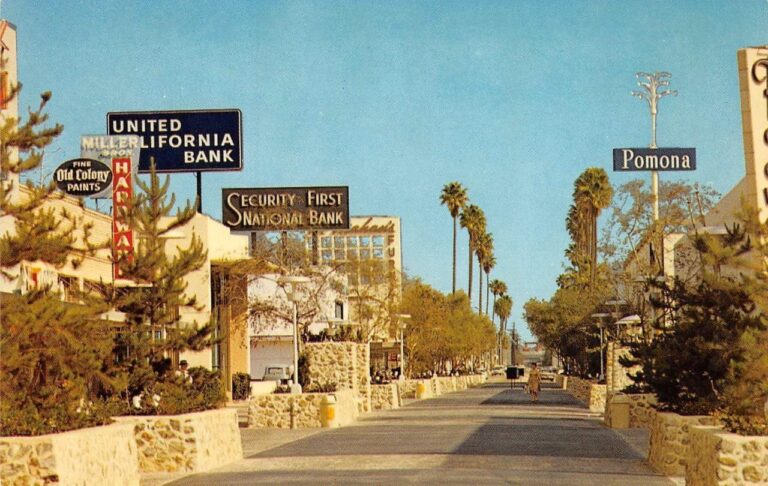

Urbanists love to celebrate, and replicate great urban spaces – and sometimes can’t understand why governments don’t: But what’s important to recall – especially for those of us under, uh, 41 – is that pedestrianized streets aren’t a new concept coming into style, they’re an old one that’s been in a three-decade decline. Samantha Matuke, Stephan Schmidt, and Wenzheng Li tracked the rise and decline of the pedestrian mall up to the onset of the pandemic. Even in the urbanizing 2000s and 2010s, 14 pedestrian malls were “demalled” against 4 streets that were pedestrianized: In a 1977 handbook promoting pedestrianization, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo admit that some of the earliest “successes” had already failed: In Pomona, California, the first year [1962] the mall received nationwide press coverage as a successful model of urban revitalization; there was a 40 percent increase in sales. But the mall was slowly abandoned by its patrons, and now, after fifteen years of operation, it is almost totally deserted. A Handbook for Pedestrian Action, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo, p. 25 One obvious reason for the failure of many other pedestrianized streets is that they were too little, too late. The pedestrian mall was one of several strategies against the overwhelming ebb tide of retail from downtowns in the postwar era. They weren’t seen as alternatives to driving, but destinations for drivers, who could park in the new, convenient downtown lots that replaced dangerous, defunct factories. A minority of the postwar-era malls survived. The predictors of survival are sort of obvious in hindsight: tourism, sunny weather, and lots of college students, among other things. Some of the streets which were “malled” and “demalled” have rebounded nicely in the 2000s. The slideshow below shows Sioux Falls’ Phillips Avenue in 1905, 1934, c. 1975, and 2015. The […]

What's the best urban path in America? Vote on Twitter this month for nominees in the Urban Paths World Cup.

American YIMBYs point to Tokyo as proof that nationalized zoning and a laissez faire building culture can protect affordability. But a great deal of that knowledge can be traced back to a classic 2014 Urban Kchoze blog post. As the YIMBY movement matures, it's time to go books deep into the fascinating details of Japan's land use institutions.

Urbanist and YIMBY Twitter had a field day dunking on Nathan J. Robinson, whose essay in his publication Current Affairs called for building new cities in California. But California really could use some new cities - and we need to think about them in primarily economic terms.