Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Sandy Ikeda and I have published a new Mercatus paper on the regressive effects of land use regulation. We review the empirical literature on how the effects of rules such as maximum density, parking requirements, urban growth boundaries, and historic preservation affect housing prices. Nearly all of the studies on the price effects of land use regulations find that — as supply and demand analysis would predict — these rules increase the price of housing. While the broad consensus on the price effects of land use regulations is probably to no surprise to Market Urbanism readers, some policy analysts continue to insist that in fact rules requiring detached, single family homes help cities maintain housing affordability.

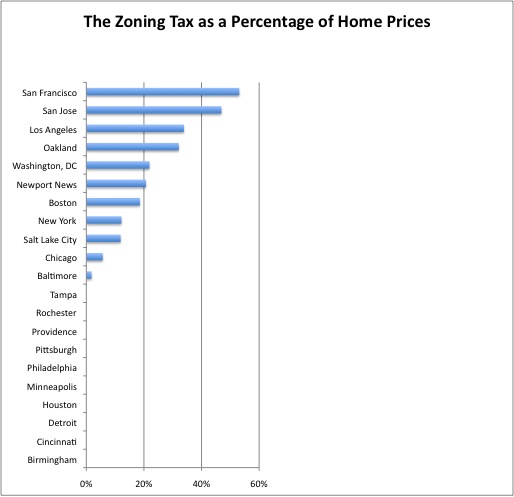

Ed Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks estimate the effects of regulations on house prices in their paper “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in Housing Prices.” They estimate what they call the “zoning tax” in 21 cities. The zoning tax indicates the proportion of housing costs that are due to land use regulations. The chart below shows the percentage of housing costs that this “tax” accounts for:

Policies that increase housing costs have a clear constituency in all homeowners, but they hurt renters and anyone who is hoping to move to an expensive city. The burden of land use regulations are borne disproportionately by low-income people who spend a larger proportion of their income on housing relative to higher income people. These regressive effects of land use policy extend beyond reducing welfare if the least-advantaged Americans. Additionally, rules that increase the cost of housing in the country’s most productive cities reduce income mobility and economic growth.

In our paper Sandy and I also discuss proposals for reducing the inefficiency of cities’ current land use regulation practices. David Schleicher has proposed some of innovative policy improvements, including a zoning budget that a city can implement to commit itself to permitting a certain amount of new development. A zoning budget would create a situation in which local policymakers are forced to make tradeoffs between different land use restrictions, as opposed to the current situation in which there is no limit to policies restricting building. Another proposal that Schleicher suggests is a tax increment local transfer, or a TILT. With TILTs, homeowners who live near new development would receive some portion of the additional property taxes that the city raises by allowing the development. The purpose of TILTs is to reduce NIMBY opposition to development.

We hope that our paper will be a helpful resource to those looking for an accessible overview of this area of research and point to future research opportunities for institutional reforms to allow for the construction of affordable housing.

Is the graph of fractions or percentages? If it’s about percentages, the zoning tax looks like a bargain but not if the graph is about fractions.

Good point! The graph currently shows the fraction of the housing costs that are due to the zoning tax. I will fix the x-axis tonight so that it’s in percentages.

Probably agree on policy recommendations, but the implications are quite unfair. Most of USA has zero “zoning tax” due to insufficient demand/sq mi for zoning to hurt. It really is apples to oranges.

Manhattan is home to lots of very wealthy people & has a population density of almost 67,000 persons per square mile. Houston is at 3,515 persons per square mile. Detroit is higher (5,142) & comparable to San Jose (5,600) in sheer density, but I don’t know if its regulations are stricter or if it is how far Detroit has fallen & how many wealthy people live in San Jose. Looking around I did find Salt Lake City at 1,666 persons per square mile, a figure that would be low even for a small town surrounded by farmland, so perhaps the implications are quite fair to Salt Lake City.

Another thing that is missing is how limiting suburbs are compared to cities. I’m sure all (or just about all) metro areas around the country have lower density outside the central city than in it. Yes Chicago has a zoning tax probably at least in part because of things like buildings in Wrigleyville being limited to four stories or other neighborhoods having single family only lots, but even there those single family lots are taking up less land area than what you see in the most of suburbia.

This study ignores the second half of what is widely accepted as the equation for total household affordability: Housing + Transportation costs. By only looking at affordability in terms housing, denser cities will always seem unaffordable, because the housing is so much more expensive. However, the whole picture needs to take into consideration types of transportation available and length of commute to have a clear understanding whether a place is affordable. The average automobile owner spends about $9,000 a year to own and maintain a vehicle. Once that cost is coupled with housing costs the full ramifications of the location where someone chooses to live becomes apparent: http://htaindex.cnt.org/map/

I agree that H+T index is the best metric, but it’s not really relevant for this discussion.

The index is helpful when comparing the costs of living in different places, but that’s not what this study is doing. This study is simply showing that land use regulations drive up the price of housing, which holds true regardless of transportation mode. It’s not looking at city A vs. city B, it’s looking at city A vs. city A with different land use policies.

In other words, NYC may actually be more affordable than it would appear, since you can live completely car free. But it’s still less affordable than it otherwise would be, because of land use constraints.

True affordability is the trade off between transportation and housing choices. Land Use regulations, such as those meant to promote denser Transit-Oriented Development, tend to promote a market that will have higher housing only cost (due to amenity requirements, construction type, increased pedestrian and bike facilities, etc.). Yet by decreasing transportation costs, those developments can be more affordable even with the higher housing cost. When comparing City A vs. City A, regulations cannot be looked at in a vacuum without taking in consideration distance from employment and access to transit. Only looking at the adverse of effect of zoning and regulations on housing cost, will indeed make growth tools such as growth boundaries look like unwise choices when dealing with affordability. That line of thinking inevitably leads to pro-sprawl policies where allowing low-density growth to spread far outside the City core, provides lower cost housing solutions, but not increased household affordability.

There is at least a century of experience in this country that says people are willing to incur the “transportation penalty” to live in less dense communities.

Induced by the giant car use subsidies

[…] How Many Land Use Regulations End Up Hurting the Poor (Market Urbanism) […]

Zoning is pre-Gentrification. Banks have supported zoning since the 1930’s so values would be stable and they could do longer-term loans – e.g. – more than five years. The bias towards home-ownership and SF detached housing has created a huge imbalance in the U.S. housing stock. Few units have been allowed in local zoning for rental units, particularly for families. Elderly and handicapped units were somewhat acceptable, but not in a unit size that was cost-effective – 100 or more units. Most rentals are SF and high maintenance. Home owners associations are another layer of cost/value protection. Little of the stock is built to be usable for generations with rehabilitation/upgrades in mind. The argon gas in windows escapes in 20 years; solar panels last 20 years; so real estate is high maintenance. The few real cities in the U.S. – where ownership of an automobile is optional, there are adequate alternatives, are globally attractive and foreign money hidden there, a higher level of gentrifying forces. Being a millionaire isn’t easy in the billionaire ghetto. Land speculation, the economic risk game easy dumb credit has fueled, has given our economy the “necessary inflation” economists claim we need. As financialization of every asset requires, real estate loans are rarely repaid – people never own the ranch. The goal is to cash out, take the money and go to a less costly area and buy something free and clear. That small town exurban area is gentrified in that move. That raises housing costs, but local wages do not respond to this. Long commutes are in order, since it impossible to live near your work – that real estate – rental or buy – to scarce. The debt game is re-fi, not repay. Property to property, the goal is equity gain for the next round, and future cash out. If you manage to own the ranch, then the loan repayment cost is gone, just maintenance (new roof, accessibility adaptation), utilities, fuel and taxes. Perhaps a reverse mortgage. Short term thinking does not effectively meet the primary need for shelter, either as an individual, family or community. The profit motive isn’t enough, the “community motive” must manage for the long term. No new iHome every six months.

Really have to disagree with one of the recommendations that would have the state more involved in local planning. The state I live in already tries to use legislation to gut local planning efforts, and not from some altruistic intention of improving the state. More to cater to the development and real estate interests that pump a lot money into their coffers.

[…] Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing” [Sanford Ikeda and Emily Washington, Mercatus via Market Urbanism] Head of Obama administration Council of Economic Advisers gives speech pinning high housing costs […]