Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

A recent “supply skeptic” paper by various academics has gotten a lot of attention in housing-related social media. The somewhat sensationalistic title is: “Inequality, not regulation, drives America’s housing affordability crisis.” But unlike most…

I recently read a report from one of Georgetown Law School’s many centers, discussing the shortage of low-income housing in six metro areas with high housing growth. * The report points out that owner-occupied…

Every so often I read a tweet or listserv post saying something like this: “If modern buildings were prettier there’d be less NIMBYism.” I always thought this claim was silly for the simple reason…

In the WSJ, Jeff Yass & Steve Moore play the world’s smallest violin for the poor homeowners who are sitting on more than half a million dollars of nominal capital gains and therefore cannot…

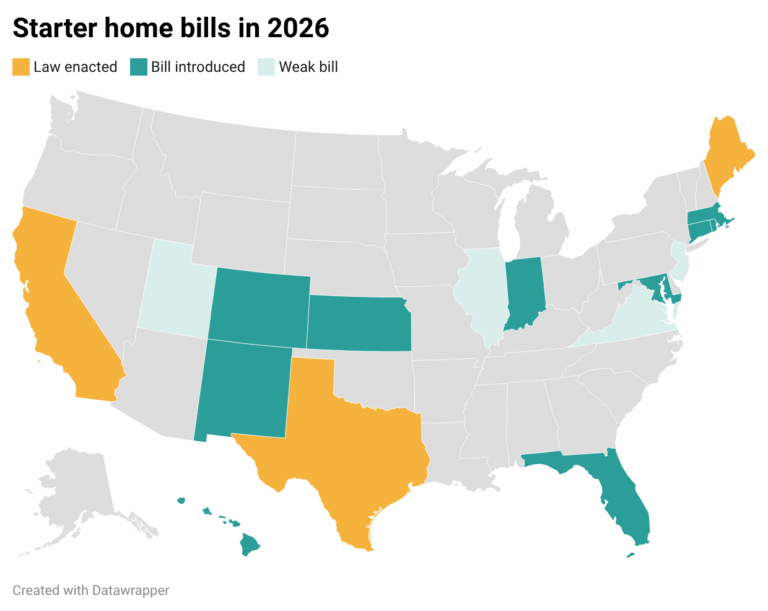

Updated 2/11 to add Connecticut; 2/5 to add Colorado; and 1/30 to add Hawaii, Kansas, New Mexico, and Rhode Island. After decades of background study and advocacy – see here for a research compilation…

The CityNerd Youtube channel has a video on the ten U.S. cities “that are becoming most city-like.” One of Citynerd’s criteria grabbed my attention: he gives credit for cities having an increase in “car-lite…

I am arguing on Twitter about whether New York City (where I live) could really build a significant amount of new housing if zoning was less restrictive. One possible argument runs something like this:…

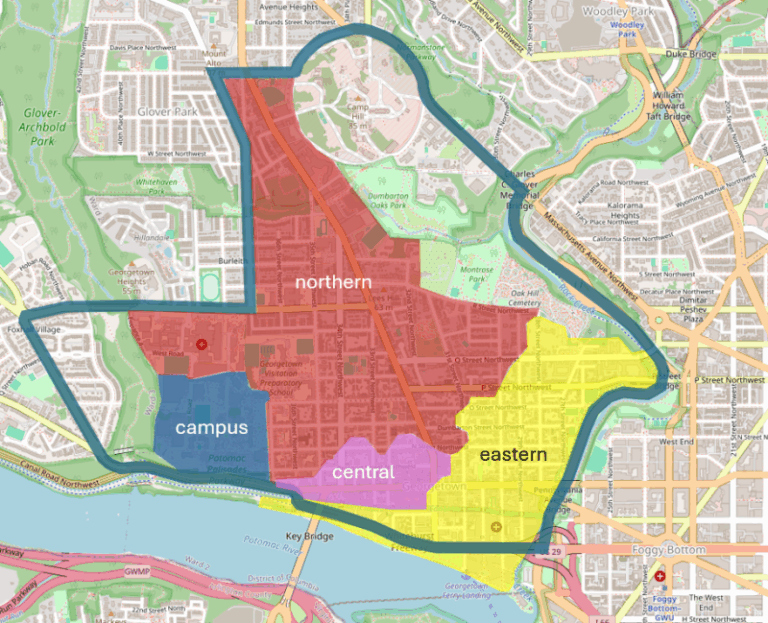

In Greater Greater Washington, my dad and I have a new editorial explaining how a ring-and-access traffic circulation plan inspired by the Netherlands can keep necessary traffic moving while delivering neighborhood streets and iconic…

One argument against Manhattan’s congestion pricing plan is that it merely redistributes congestion and pollution to nearby neighborhoods and suburbs, as drivers choose alternative routes that avoid midtown and downtown Manhattan. If this was…

Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro has received some publicity for stating: “If you can’t afford to live here [in New York City] maybe you should not live here.” From the standpoint of advice to individuals,…