Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In my regular discussions of U.S. zoning, I often hear a defense that goes something like this: “You may have concerns about zoning, but it sure is popular with the American people. After all, every state has approved of zoning and virtually every city in the country has implemented zoning.” One of two implications might be drawn from this defense of Euclidean zoning: First, perhaps conventional zoning critics are missing some redeeming benefit that obviates its many costs. Second, like it or not, we live in a democratic country and zoning as it exists today is evidently the will of the people and thus deserves your respect. The first possible interpretation is vague and unsatisfying. The second possible interpretation, however, is what I take to really be at the heart of this defense. After all, Americans love to make “love it or leave it” arguments when they’re in the temporary majority on a policy. But is Euclidean zoning actually popular? The evidence for any kind of mass support for zoning in the early days is surprisingly weak. Despite the revolutionary impact that zoning would have on how cities operate, many cities quietly adopted zoning through administrative means. Occasionally city councils would design and adopt zoning regimes on their own, but often they would simply authorize the local executive to establish and staff a zoning commission. Houston was among the only major U.S. city to put zoning to a public vote—a surefire way to gauge popularity, if it were there—and it was rejected in all five referendums. In the most recent referendum in 1995, low-income and minority residents voted overwhelmingly against zoning. Houston lacks zoning to this day. Meanwhile, the major proponents of early zoning programs in cities like New York and Chicago were business groups and elite philanthropists. Where votes were […]

The adoption of zoning as a means of preventing external costs led to inefficient use of land and caused many individuals to suffer great unfairness.

by Samuel R Staley Before the twentieth century land-use and housing disputes were largely dealt with through courts using the common-law principle of nuisance. In essence if your neighbor put a building, factory, or house on his property in a way that created a measurable and tangible harm, courts could intervene on behalf of a complainant to force compensation or stop the action. This pro-property rights approach maximized liberty and minimized the ability of citizens and elected officials to politicize the development process. This changed with the Progressive movement. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Progressives argued that government should become more professional. Rather than being limited, government should use its resources to pursue the “public interest,” loosely defined as whatever the general public decided through democratic processes was the proper scope of government. Legislatures and, by extension, city commissions made up of elected citizens would set policy and goals while a cadre of trained professionals would use the techniques of scientific management to implement policies. One of the leading Progressives of the day, Woodrow Wilson, was skeptical of the value of elected bodies such as Congress because they interfered with scientific management of government. While many in the twenty-first century might be tempted to dismiss this public-interest view of government—indeed an entire academic subdiscipline, Public Choice, has emerged to demonstrate the foibles of governments and explore “government failure”—Progressive ideas held a lot of appeal at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition to national concerns over industries such as oil, steel, and railroads, local governments were rife with corruption, waste, and inefficiency. Reforms, such as the city-manager form of government, civil-service exams, and in some cases even municipal ownership of utilities, were thought to provide more transparency and accountability than the patronage-laden times of political bosses. (Today municipal […]

This post was originally published at mises.org and reposted under a creative commons license. It’s no secret that in coastal cities — plus some interior cities like Denver — rents and home prices are up significantly since 2009. In many areas, prices are above what they were at the peak of the last housing bubble. Year-over-year rent growth hits more than 10 percent in some places, while wages, needless to say, are hardly growing so fast. Lower-income workers and younger workers are the ones hit the hardest. As a result of high housing costs, many so-called millennials are electing to simply live with their parents, and one Los Angeles study concluded that 42 percent of so-called millennials are living with their parents. Numbers were similar among metros in the northeast United States, as well. Why Housing Costs Are So High? It’s impossible to say that any one reason is responsible for most or all of the relentless rising in home prices and rents in many areas. Certainly, a major factor behind growth in home prices is asset price inflation fueled by inflationary monetary policy. As the money supply increases, certain assets will see increased demand among those who benefit from money-supply growth. These inflationary policies reward those who already own assets (i.e., current homeowners) at the expense of first-time homebuyers and renters who are locked out of homeownership by home price inflation. Not surprisingly, we’ve seen the homeownership rate fall to 50-year lows in recent years. But there is also a much more basic reason for rising housing prices: there’s not enough supply where it’s needed most. Much of the time, high housing costs come down to a very simple equation: rising demand coupled with stagnant supply leads to higher prices. In other words, if the population (and household formation) is […]

Caos Planejado, in conjunction with Editora BEI/ArqFuturo, recently published A Guide to Urban Development (Guia de Gestão Urbana) by Anthony Ling. The book offers best practices for urban design and although it was written for a Brazilian audience, many of its recommendations have universal applicability. For the time being, the book is only available in Portuguese, but after giving it a read through, I decided it deserved an english language review all the same. The following are some of the key ideas and recommendations. I hope you enjoy. GGU sets the stage with a broad overview of the challenges facing Brazilian cities. Rapid urbanization has put pressure on housing prices in the highest productivity areas of the fastest growing cities and car centric transportation systems are unable to scale along with the pace of urban growth. After setting the stage, GGU splits into two sections. The first makes recommendations for the regulation of private spaces, the second for the development and administration of public areas. Reforming Regulation Section one will be familiar territory for any regular MU reader. GGU advocates for letting uses intermingle wherever individuals think is best. Criticism of minimum parking requirements gets its own chapter. And there’s a section a piece dedicated to streamlining permitting processes and abolishing height limits. One interesting idea is a proposal to let developers pay municipalities for the right to reduce FAR restrictions. This would allow a wider range of uses to be priced into property values and create the institutional incentives to gradually allow more intensive use of land over time. Meeting People Where They Are Particular to the Brazilian experience is a section dedicated to formalizing informal settlements, or favelas. These communities are found in every major urban center in the country and often face persistent, intergenerational poverty along with […]

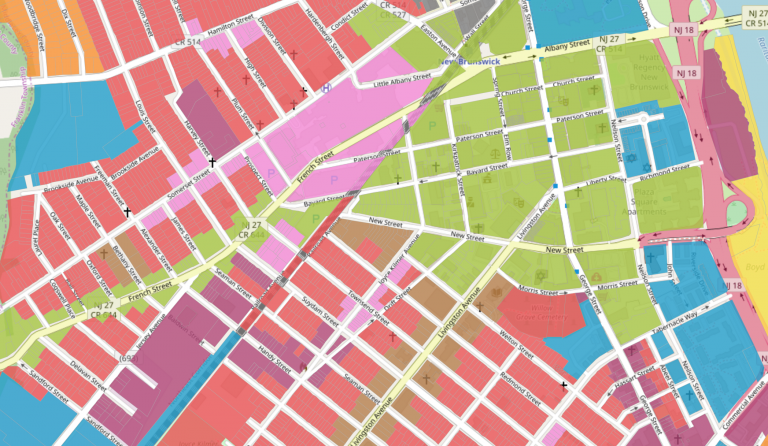

I just finished reading Richard Florida’s new book, The New Urban Crisis. Florida writes that part of this “crisis” is the exploding cost of housing in some prosperous cities. Does that make him a market urbanist? Yes, and no. On the one hand, Florida criticizes existing zoning laws and the NIMBYs who support them. He suggests that these policies not only raise housing prices, but by doing so harm the economy as a whole. For example, he writes that if “everyone who wanted to work in San Francisco could afford to live there, the city would see a 500 percent increase in jobs… On a national basis, [similar results] would add up to an annual wage increase of $8775 for the average worker, adding 13.5 percent to America’s GNP – a total gain of nearly $2 trillion” (p 27). On the other hand, Florida is not ready to endorse the idea that “we can make our cities more affordable… simply by getting rid of existing land use restrictions” because “the high cost of land in superstar neighborhoods makes it very hard if not impossible, for the private market to create affordable housing in their vicinity. Combine the high costs of land with the high costs of high-rise construction and the result is more high-end luxury housing.” (p. 28). I don’t find his point persuasive, for a variety of reasons. First, as I have written elsewhere, land prices are often quite volatile. Second, the overwhelming majority of any region’s housing is not particularly new; even in high-growth Houston, only 2 percent of housing units were built after 2010. Thus, new market-rate housing is likely to affect rents by affecting the price of older housing, rather than by bringing new cheap units into the market. Florida also writes that “too much density can […]

It is because every individual knows little and, in particular, because we rarely know which of us knows best that we trust the independent and competitive efforts of many to induce the emergence of what we shall want when we see it. — Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty Imagine the perfect city. If you have a clear picture in mind, you’re not alone. Tsars, emperors, and prophets have been trying to build perfect cities for millennia. With the emergence of the field of urban planning and modern social science, everyone from stenographers to industrialists to independent architects have joined in. For Ebenezer Howard, the perfect city was the Garden City, a corporate-owned residential satellite on the outer edge of town. For Le Corbusier, it was the Ville Radieuse, full of “skyscrapers in the park” and elevated highways. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was Broadacre City, a dispersed anti-city full of single-family homes on one-acre lots. Each reflects a distinct vision of urban life, and each seems to have as many opponents as it does proponents. Thankfully, few of these plans have ever been implemented in full on a mass scale. Yet “perfect city” thinking—the view that one particular vision of urban form should be imposed by planners—has manifested itself in small ways in cities around the world through the construction and enforcement of specific theories of how a city should work. This approach to urban form involves expanding urban planning beyond prudentially managing infrastructure and mitigating destructive negative externalities and toward enforcing and preserving particular lifestyle and aesthetic preferences. Consider: while Ville Radieuse was never built, many cities bulldozed traditional urban neighborhoods to construct the urban elevated highways of Le Corbusier’s dreams. While Broadacre City never moved beyond the model stage, many suburban communities still zone minimum lot sizes […]

Matthew Yglesias has a group of tweets that begin with this: Someone needs to give me an Oscar one of these years so I can subject America to a tedious discussion of land use regulation. — Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) February 27, 2017 “In the movies, there is no minimum lot size or maximum lot occupancy; we fill provide as much or as little parking as we want.” — Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) February 27, 2017 “Fences is a powerful reminder that single-family zoning is not enough to make the American dream a reality.” — Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) February 27, 2017

Planners, like all professions, have their own useful mythologies. A popular one goes something like this: “Many years ago, us planners did naughty things. We pushed around the poor, demolished minority neighborhoods, and forced gentrification. But that’s all over today. Now we protect the disadvantaged against the vagaries of the unrestrained market.” The seasoned—which is to say, cynical—planner may knowingly roll her eyes at this story, but for the true believer, this story holds spiritual significance. By doing right today, the reasoning goes, planners are undoing the horrors of yesterday. This raises the question: are planners doing right today? That’s not at all clear. Just ask Hinga Mbogo. After emigrating from Kenya, Mr. Mbogo opened Hinga’s Automotive in East Dallas in 1986. Mr. Mbogo’s modest business is precisely the kind of thing cities need, providing a service for the community, taxes for the city, and blue-collar jobs. While perhaps not of the “creative class,” Mr. Mbogo and his small business represent the type of creative little plan that cities cultivate and depend on. Hinga’s Automotive has thrived for 19 years and looked primed for another 19. Unfortunately for Mr. Mbogo, Dallas planners had other plans. In 2005, the city rezoned the area to prohibit auto-related businesses. While rezonings—particularly upzonings—aren’t necessarily a bad thing, Dallas planners opted to force their vision through and implemented a controversial planning technique known as “amortization.” Normally when planners rezone an area, they allow existing uses that run afoul of the new code to continue operating indefinitely. These are known as “non-conforming uses” and they’re common in neighborhoods across the country, often taking the form of neighborhood groceries, restaurants, and small industrial shops. Yet under amortization, the government forces non-conforming uses to cease operating without any compensation. In the case of Hinga’s Automotive, this means […]

The Atlantic Magazine’s Citylab web page ran an interview with Joel Kotkin today. Kotkin seems to think we need more of something called “localism”, stating: “Growth of state control has become pretty extreme in California, and I think we’re going to see more of that in the country in general, where you have housing decisions that should be made at local level being made by the state and the federal level too. You have general erosion of local control.” In fact, land use decisions are generally made by local governments–which is why it is so hard to get new housing built. This is as true in California as it is anyplace else; when Gov. Brown tried to make it easier for developers to bypass local zoning so they can build new housing, the state legislature squashed him. Local zoning has become more restrictive over time, not less. And the fact that state government has added additional layers of regulation doesn’t change that reality. But did the Atlantic note this divergence from factual reality, or even ask him a follow-up question? No, sir. Shame on them!