Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Viewing cities as spontaneous orders and not as works of art helps to explain the tradeoff between scale and order, as well as the role of time in softening the severity of that tradeoff. Complexity and creativity are at odds with scale and the comprehensiveness of design because increasing scale impinges on the action spaces where creative, informal contact tends to happen. Design might complement that informal contact to a point, but beyond a fairly low level it begins to overwhelm it. Again, small is not always beautiful, and big is sometimes unavoidable. That makes it all the more important to understand the impact of scale and design on spontaneous social orders. That applies as much to private as it does to public projects. When the designs are small relative to the surrounding social milieu, the downside of the tradeoff isn’t very steep. The problems start when budget constraints are soft and projects become mega-projects and mega-projects become giga-projects. I don’t want to sound too ideological – Jane Jacobs somehow avoided being ideologically pigeonholed all her life – but soft budget constraints are primarily the domain of governmental and, especially, of so-called public-private developments: Those elephantine-starchitectural-wonder-complexes that too-often strive for off-the-charts wow-factors. Without legal privileges, subsidies, and eminent domain, could the scale and degree of design of purely privately funded developments even begin to compare to those? I don’t think so. The rules of the game of urban processes interact in complex ways. So deliberately changing some of those rules to achieve a particular outcome is akin to trying to impose a particular design on the social order, killing the social order in the process, although perhaps preserving the appearance of life. Taxidermy again. (That, by the way, is why I have problems with landmarks preservation on the scale practiced […]

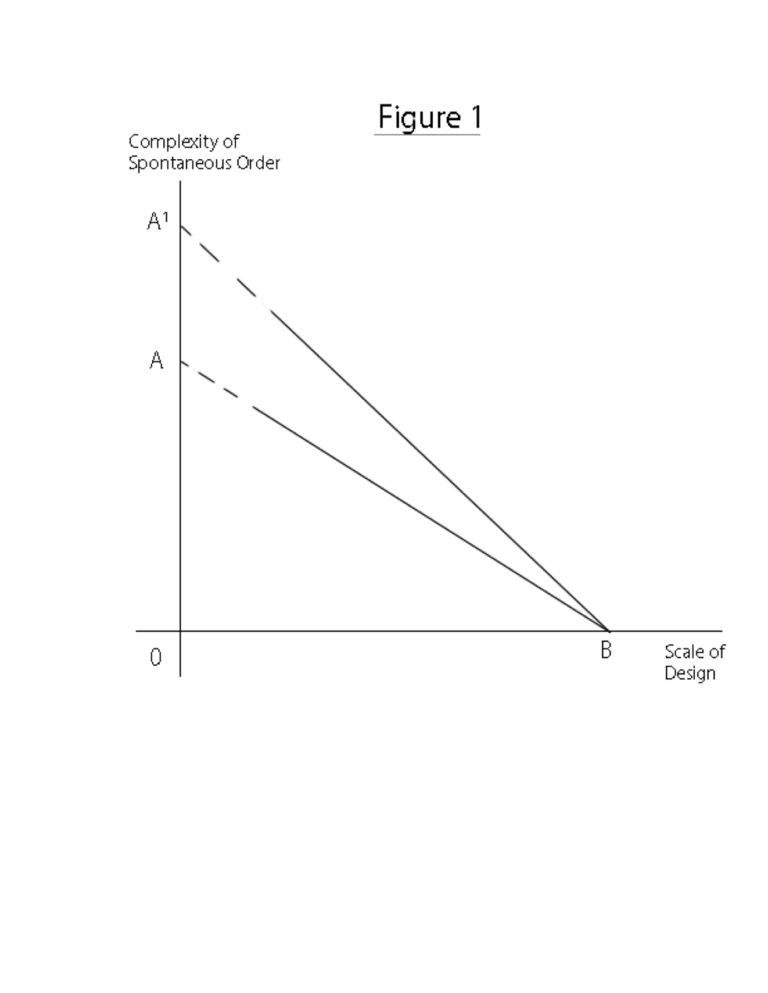

We can visualize the tradeoff between the scale of design and the complexity and spontaneity of a social order as a downward-sloping curve. A sort of “scale-versus-order-possibilities frontier.” In addition to scale and spontaneous order/complexity, a third element I would add to the tradeoff is the passage of time. You can to some extent plan for complementarity, but you can’t really plan for spontaneous complexity and intricacy. [Helpful to bring in capital theory here?] Fortunately, time allows people to some extent to adjust social networks and physical spaces to better complement their own plans, in ways that the designer could not foresee. That is, for any given scale, time lets people figure out novel uses for, or changes to, the space as originally designed. Those unthought-of uses constitute an increase in the level of complexity in a spontaneous order. Over time, then, the frontier can shift outward. Figure 1 reflects these relations: The scale of a structure and the designed or planned uses of the space within that structure are of course two different things. Increasing the dimensions of a room doesn’t necessarily mean the elements that go into its design become more complex. But to keep things simple, Figure 1 treats scale and design as highly positively correlated. [Is this necessary?] Thus, as scale increases so do the designed elements – you move from point A to point B – and together they decrease the potential for spontaneous order. [But think about the tradeoff between scale and order, keeping design constant. Just increasing scale does seem to increase the designed/planned element in a previously undesigned space.] Then, as time passes, the frontier shifts up from AB to A’B, where point B represents the case where the structure occupies100% of the relevant action space. So for any given scale, the […]

As Jacobs explains in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works that are under the control of the artist…the essence of the process is disciplined, highly discriminatory selectivity from life. In relation to the inclusiveness and the literally endless intricacy of life, art is arbitrary, symbolic and abstracted…To approach a city, or even a city neighborhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, is to make the mistake of attempting to substitute art for life. The results of such profound confusion between art and life are neither art nor life. They are taxidermy.” (1961: 372-3, emphasis original) So how do we avoid turning the results of urban design into taxidermy and killing off a city by planning? I think the short answer is that we avoid it by recognizing that there’s a tradeoff between the scale of a design and the degree of spontaneity, complexity, and intricacy in the resulting social order that the design allows. Now, saying that a city cannot be a work of art doesn’t mean of course that a city cannot be beautiful or that deliberate design can never enhance that beauty. But I am suggesting that beauty that is designed as a work of art is fundamentally different from the undersigned beauty that emerges from a lifetime of experience. The skillfully made-up face of a fashion model and the face of a 90-year-old grandmother are both beautiful, but in profoundly different ways. Niels Gron, quoted in Gerard Koeppel’s City of a Grid: How New York Became New York: Before I came to this country, and in all the time […]

“In fine, I see from our example that human society holds and is knit together at any cost whatever. Whatever position you set men in, they pile up and arrange themselves by moving and crowding together just as ill-matched objects, put in a bag without order, find of themselves a way to unite and fall into place together, often better than they could have been arranged by art.” Michel de Montaigne

The starting point for Jacobs’s analysis and the focus of much of her thought is the city, its nature and significance. There are plenty of books out there that in some way celebrate cities. Many describe cities as engines of economic development, wellsprings of art and culture, and incubators of ideas religious, social, and scientific. But few go very far in explaining why and how all that usually happens in a city. Fewer still view the urban processes as expressions of “emergence,” or what some social theorists describe using the related term “spontaneous order.” That is the perspective of this book and its main contribution: To look closely at what makes a city a spontaneous order and an engine of innovation, and to trace the analytical and policy consequences of viewing it this way. Jane Jacobs is one of those exceptions, indeed an outstanding one. In fact, she is probably the first to carefully examine, not only the nature and significance of cities, but to distill realistic principles that govern urban systems and to analyze the mechanisms of economic change that follow from those principles. Her analysis of the relation between the design of public space and social interaction offer insights that complement, and often exceed, those of Max Weber, Henri Pirenne, Georg Simmel (pdf), Kevin Lynch, and others. Her work also has deep connections with modern social theorists such as F.A. Hayek, Elinor Ostrom, Mark Granovetter, and Geoffrey West. But she was not the first to develop conceptual tools congenial to understanding urban processes as emergent, spontaneous orders. In fact they have largely been available for decades in the field of economics, although few professional economists, including urban economists, have fully appreciated the urban origins of many of their standard concepts and tools of analysis. Indeed, there is a […]

Cities are fantastically dynamic places, and this is strikingly true of their successful parts, which offer a fertile ground for the plans of thousands of people. – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities For most of the field’s history, prominent urban planning theorists have taken for granted that cities require extensive central planning. With the question framed as “To plan or not to plan?” students and practitioners answer with an emphatic “Yes,” subsequently setting out to impose their particular ideal order on what they perceived to be, as Lewis Mumford put it, “solidified chaos.” Whether through the controlled centralization of Le Corbusier or the controlled decentralization of Ebenezer Howard and Frank Lloyd Wright, cities were to be just that: controlled. When in 1961 Jane Jacobs set out to attack the orthodox tradition of urban planning, it was this dogma that landed squarely in her crosshairs. With her characteristically deceptive simplicity, she invites us to ask, “Who plans?” While many take Jacobs’ essential contribution to be her insights into urban design, her subversion begins at the theoretical level in the introduction to The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Despite their diverse aesthetic preferences, Corbusier and Howard share much in common. Both assume that planning entails the enshrining of a single plan and the suppression of all other individual plans. Both insist on imposing a “pretended order” on the “real order,” treating the city as a simple machine rather than a manifestation of organized complexity. Like Adam Smith’s “man of system,” each thinker was “so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he [could not] suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it.” Jane Jacobs’ critique of this orthodox tradition unfolds in three steps, closely following F.A. Hayek’s argument in […]

Mathieu Helie has been writing at a blog he calls Emergent Urbanism. His most recent post is the first part of a series that will be published as an entire article entitled “The Principles of Emergent Urbanism” at International Journal of Architectural Research. This first part of the series, and hopefully the entire published article gives a great introduction to the concept Helie names “Emergent Urbanism.” In my opinion as a Market Urbanist, Mathieu’s most remarkable contributions to urbanism revolve around the concepts of “emergence” as it relates to urban patterns, particularly with regards to Hayek’s ideas about “emergent order” or “spontaneous order”. As Mathieu writes: How is it possible for what is obviously a human artifact to arise as if by an act of nature? The theory of a spontaneous order provides an explanation. According to Friedrich A. von Hayek (Hayek, 1973) a spontaneous order arises when multiple actors spontaneously adopt a set of actions that provides them with a competitive advantage, and this behavior creates a pattern that is self-sustaining, attracting more actors and growing the pattern. This takes place without any of the actors being conscious of the creation of this pattern at an individual level. The spontaneous order is a by-product of individuals acting in pursuit of some other end. In this way cities appear as agglomerations of individually initiated buildings along natural paths of movement, which originally do not require any act of production as dirt paths suffice. As the construction of individual buildings continues the most intensely used natural paths of movement acquire an importance that makes them unbuildable and these paths eventually form the familiar “organic” pattern of streets seen in medieval cities. This process still takes place today in areas where government is weak or dysfunctional, notably in Africa where urban planning […]