Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Inclusionary Zoning is an Oxymoron The term “Inclusionary Zoning” gives a nod to the fact that zoning is inherently exclusionary, but pretends to be somehow different. Given that, by definition, zoning is exclusionary, Inclusionary Zoning completely within the exclusionary paradigm is synonymous with Inclusionary Exclusion. What is Inclusionary Zoning? “Inclusionary Zoning” is a policy requiring a certain percentage of units in new developments to be affordable to certain income groups. Sometimes, this includes a slight loosening of restrictions on the overall scale of the development, but rarely enough loosening to overcome the burden of subsidizing units. Many cities, particularly the most expensive ones, have adopted Inclusionary Zoning as a strategy intended to improve housing affordability. Often, demand for below-market units are so high, one must literally win a lottery to obtain a developer-subsidized unit. Economics of Exclusion We must first acknowledge the purpose of zoning is to EXCLUDE certain people and/or businesses from an area. Zoning does this by limiting how buildings are used within a district, as well as limiting the scale of buildings . These restriction cap the supply of built real estate space in an area. As we know from microeconomics, when rising demand runs into this artificially created upward limit on supply, prices rise to make up the difference. As every district in a region competes to be more exclusive than its neighbors through the abuse of zoning, regional prices rise in the aggregate. Since the invention of the automobile, and subsequent government overspending on highways, sprawl has served as the relief valve. We’ve built out instead of up for the last several decades and this sprawl has relieved some of the pressure major metropolitan areas would have otherwise felt. In fact, it’s worked so well–and led to the abuse of zoning rules for such a long time–that exclusionary zoning has become the accepted paradigm. Zoning is the default flavor of […]

[this is a pilot for a regular weekly series rounding-up the week’s happenings in the world of Market Urbanism. I’d love to get your feedback in the comments or contact us directly. If the response is positive, we’ll continue it.] 1. Here at Market Urbanism, Scott Beyer wrote about Charlottesville developer Oliver Kuttner for his series on America’s Progressive Developers. Not uncommon in US cities, Kuttner faces ever increasing obstacles to innovative development: I do believe that every time you add an extra layer in city hall, you make interesting buildings less likely. 2. Scott was also quoted in The New Tropic about Miami gentrification: If you have a population increase and you don’t increase housing, people will get pushed out read the rest of the quote and article here. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook group: Nolan Gray shared some encouraging news about D.C.‘s new zoning code. Similar good news from Hartford, Connecticut! via John Morris China to build worlds largest Mega-City. “What could possibly go wrong?” asks Mark Frazier. Trump thinks Eminent Domain is wonderful via Anthony Ling. 4. Elsewhere: Michael Lewyn at Planetizen: Right to the City Daniel Hertz at City Observatory: In some cities, the housing construction boom is starting to pay off Dan Savage jumps on the SFyimby bandwagon: When It Comes to Housing, San Francisco Is Doing It Wrong, Seattle Is Doing It Right, Cont. Jonathan Coppage at The American Conservative: Why San Francisco Has to Build Up Kim-Mai Cutler at TechCrunch: A Long Game Chicago‘s proposed anti-Airbnb ordinance limits the number of nights a host can have guests, an additional 2% tax on top of Chicago’s 17.5% hotel tax, and possible jail-time for users! Let’s hope the opposition triumphs. Strong Towns interviews @stuckbertha (that Tunnel Boring Machine that got stuck 1,000 ft under Seattle) during #NONEWROADS week 5. And finally, Stephen Smith‘s tweet of […]

In a recent 48 Hills post, housing activist Peter Cohen aimed a couple rounds of return fire at SPUR’s Gabriel Metcalf. The post comes in response to Mr. Metcalf’s own article critiquing progressive housing policy. Mr. Cohen bounces around a bit, but he does repeat some frequently used talking points worth addressing. Trickle-down economics Mr. Cohen calls the argument for market-rate construction ‘trickle down economics’. Trickle down economics actually refers to certain macro theories popularized during the Reagan years. These models assumed a higher marginal propensity to save among wealthier individuals. And given this assumption, some economists concluded that reducing top marginal tax rates would result in higher savings. This would then mean higher levels of investment which would, in turn, have a positive effect on aggregate output. And from there we get the idea of a rising tide lifting all ships. Note that none of that has anything to do with housing policy. Labeling something ‘trickle down’ is a way to delegitimize certain policy proposals by associating them with Ronald Reagan. It’s somewhere between rhetorically dishonest and intellectually lazy. Though to be fair, it’s probably pretty effective in San Francisco. The concept Mr. Cohen is trying to critique is actually called filtering. In many instances, markets do not produce new housing at every income level. But they do produce housing across different income levels over time. Today’s luxury development is tomorrow’s middle income housing. The catch, however, is that supply has to continually expand. If not, prices for even dilapidated housing can go through the roof. For a more thorough explanation, see SFBARF’s agent based housing model. If you build it, they’ll just come But even accurately defined, Mr. Cohen still objects to the concept of filtering. He cites an article by urban planning authority William Fulton to make […]

There’s a proposal to place a moratorium on all market rate construction in the Mission District, one of San Francisco’s most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods. Needless to say the proposal has sparked a debate. And Dan Ancona’s Putting Market Fundamentalism On Hold is another rock hurled into that particular fray. But in trying to take the anti-moratorium/pro-supply camp to task, it falls into the same unproductive bomb hurling we’ve been watching now for years. The following are a few thoughts on some of the points Mr. Ancona makes in his recent piece. Talking Past Each Other The first point is about a fundamental misunderstanding of the motivations behind the moratorium. Mr. Ancona makes this mistake, but so do the exasperated anti-moratorium/pro-supply advocates he quotes at the beginning of his piece. Hint: The moratorium is not about lowering housing prices. To be sure, the anti-moratorium camp wants lower aggregate housing prices throughout San Francisco and the entire region. The indisputable way to accomplish this goal is by building more housing. And as far as the anti-moratorium camp is concerned, this includes plenty of below market rate (BMR) construction to mitigate some of the distributional effects of development. For the pro-moratorium camp, however, this doesn’t cut it. Lower aggregate prices are not their goal. Their goal is keeping the existing population of the Mission intact and in place. Even a 70/30 ratio of market rate development to BMR construction wouldn’t do that. There would still be demographic churn and this is specifically what they want to avoid. For the pro-moratorium camp, lower housing prices are all well and good, but not if that means the dispersal of the existing community in the process. Searching for the Endgame The second issue is that there’s no endgame for the pro-moratorium camp. Mr. Ancona seems to think there is, but doesn’t go […]

This post draws heavily from Tom W. Bell’s “Want to Own a City?” and would not have been possible without his prior writing and research The “Right to the City” is an old marxist slogan that’s as catchy as it is ill-defined. Neither the phrase’s originator Henri Lefebvre, nor David Harvey, a more recent proponent, seem to have articulated the idea in any meaningful way. Even the Right to the City Alliance stops short of explaining what the right actually is. When it comes up, it’s typically alongside a claim that something is being stolen or taken away from long-standing communities, as if neighborhoods were sovereign territory suffering from an invasion. For practical purposes, no one has any right to reside in any place beyond their ability to pay. But if the desire is for a way in which communities could actually own the places they call home, perhaps the Right to the City should be a property right. Public Ownership through Private Property What’s the difference between a private company and a municipal corporation? You can own the former but not the latter. Investors have clearly delineated property rights in their corporations. Residents have no equivalent ownership rights in their cities. But what if living in a city meant owning a piece of it as a legal entity as well? Imagine that a city issued shares to its residents. Shares would vest over time and long-time residents would have more equity than new arrivals. Now assume that this city took in all of its revenue through land value taxation and that land revenues were used to pay dividends to the city’s resident-shareholders. Instead of facing displacement, incumbent residents would benefit from rising demand to live in their city. Shares might also be used to weight the voting system. More shares could […]

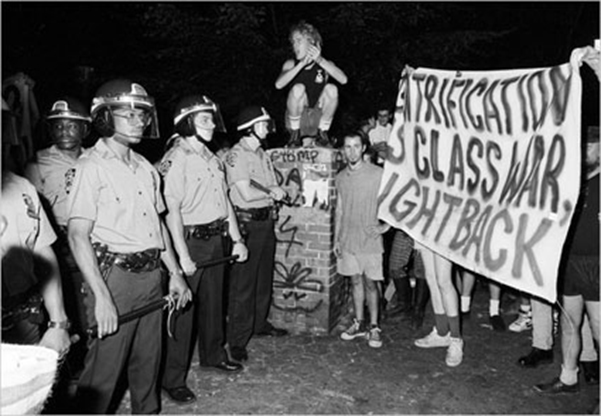

Gentrification is the result of powerful economic forces. Those who misunderstand the nature of the economic forces at play, risk misdirecting those forces. Misdirection can exasperate city-wide displacement. Before discussing solutions to fighting gentrification, it is important to accept that gentrification is one symptom of a larger problem. Anti-capitalists often portray gentrification as class war. Often, they paint the archetypal greedy developer as the culprit. As asserted in jacobin magazine: Gentrification has always been a top-down affair, not a spontaneous hipster influx, orchestrated by the real estate developers and investors who pull the strings of city policy, with individual home-buyers deployed in mopping up operations. Is Gentrification a Class War? In a way, yes. But the typical class analysis mistakes the symptom for the cause. The finger gets pointed at the wrong rich people. There is no grand conspiracy concocted by real estate developers, though it’s not surprising it seems that way. Real estate developers would be happy to build in already expensive neighborhoods. Here, demand is stable and predictable. They don’t for a simple reason: they are not allowed to. Take Chicago’s Lincoln Park for example. Daniel Hertz points out that the number of housing units in Lincoln Park actually decreased 4.1% since 2000. The neighborhood hasn’t allowed a single unit of affordable housing to be developed in 35 years. The affluent residents of Lincoln Park like their neighborhood the way it is, and have the political clout to keep it that way. Given that development projects are blocked in upper class neighborhoods, developers seek out alternatives. Here’s where “pulling the strings” is a viable strategy for developers. Politicians are far more willing to upzone working class neighborhoods. These communities are far less influential and have far fewer resources with which to fight back. Rich, entitled, white areas get down-zoned. Less-affluent, disempowered, minority […]

Co-authored with Anthony Ling, editor at Caos Planejado Gentrification Gentrification is the process through which real estate becomes more valuable and, therefore, more expensive. Rising prices displace older residents in favor of transplants with higher incomes. This shouldn’t be confused with the forced removal of citizens via eminent domain or “slum clearance.” Ejecting residents by official fiat is a different problem entirely. A classic example of gentrification is that of Greenwich Village, New York. Affluent residents initially occupied the neighborhood. It later became the city’s center for prostitution, prompting an upper-middle class exodus. Low prices and good location would later attract the textile industry. This was the neighborhood’s first wave of gentrification. But after a large factory fire, the neighborhood was once again abandoned. Failure, however, would give way to unexpected success: artists and galleries began to occupy the vacant factories. These old industrial spaces soon became home to one of the most important movements in modern art. In Greenwich Village, different populations came and went. And in the process they each made lasting contributions to New York’s economic and cultural heritage. This was only possible because change was allowed to take place. But change isn’t always easy. As a neighborhood becomes more popular, it also becomes more expensive. Tensions run high when long-time residents can’t afford rising rents. Some begin to call for rent controls or other measures to prevent demographic churn. But rent control is a temporary fix at best; in the longer term, its effects are negative. By reducing supply, rent control tends to drive up the cost of housing. And in the face of price controls, landlords may seek to exit the rental market entirely, further exacerbating any housing shortage. What, then, does this mean for urban development? How can cities evolve without completely displacing their middle and […]

Want to live in San Francisco? No problem, that’ll be $3,000 (a month)–but only if you act fast. In the last two years, the the cost of housing in San Francisco has increased 47% and shows no signs of stopping. Longtime residents find themselves priced out of town, the most vulnerable of whom end up as far away as Stockton. Some blame techie transplants. After all, every new arrival drives up the rent that much more. And many tech workers command wages that are well above the non-tech average. But labelling the problem a zero sum class struggle is both inaccurate and unproductive. The real problem is an emasculated housing market unable to absorb the new arrivals without shedding older residents. The only solution is to take supply off its leash and finally let it chase after demand. Strangling Supply From 2010 to 2013, San Francisco’s population increased by 32,000 residents. For the same period of time, the city’s housing stock increased by roughly 4,500 units. Why isn’t growth in housing keeping pace with growth in population? It’s not allowed to. San Francisco uses what’s known as discretionary permitting. Even if a project meets all the relevant land use regulations, the Permitting Department can mandate modifications “in the public interest”. There’s also a six month review process during which neighbors can contest the permit based on an entitlement or environmental concern. Neighbors can also file a CEQA lawsuit in state court or even put a project on the ballot for an up or down vote. This process is heavily weighted against new construction. It limits how quickly the housing stock can grow. And as a result, when demand skyrockets so do prices. To remedy this, San Francisco should move from discretionary to as-of-right permitting. In an as-of-right system, it’s much […]

D.C.'s Uline Arena – once a trash transfer station, now an indoor parking lot American cities have been on the rebound for about two decades now, with once moribund residential and commercial neighborhoods springing back to life.

When libertarians (and liberals) argue that increasing the supply of urban housing will lower the price of urban housing, they’re drawing on some pretty basic and well-established economic concepts. And yet, the coexistence of gentrification and housing supply growth seem to put a lie to that theory – in cities across America, we see neighborhoods adding housing while still seeing rapid increases in the price of housing. From the point of view of the poor and often non-white residents who are being pushed out, the market remedy of increasing supply just doesn’t seem to be working. …