Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

For a reading group, I recently read two papers about the costs and (in)efficiencies around land assembly. One advocated nudging small landowners into land assembly; the other is an implicit caution against doing so. Graduated Density Zoning Although he’s mostly known for parking research and policy, Donald Shoup responded to the ugliness of eminent domain in Kelo v. City of New London, with a 2008 paper suggesting “graduated density zoning” as a milder alternative. Graduated density zoning would allow greater densities or higher height limits for larger parcels – so that holdouts would face greater risk. Samurai to Skyscrapers Junichi Yamasaki, Kentaro Nakajima, and Kensuke Teshima’s paper, From Samurai to Skyscrapers: How Transaction Costs Shape Tokyo, is a fascinating and technical account of how sweeping changes put the relative prices of different-sized lots on a roller-coaster from the 19th century to the present. First, large estates were mandated as a way for the shogun to keep nobles under his close control. Then, with the Meiji Restoration, the nobles were released to sell their land, swamping the market and depressing prices. The value of land in former estate areas stayed low into the 1950s. But with the advent of skyscrapers – which need large base areas – the old estate areas first matched and then exceeded neighboring small-lot areas in central Tokyo. A meta-lesson from this reversal is that “efficiency” is a time-bound concept. One can imagine a 1931 urban planner imposing a tight street grid and forcing lot subdivision to unlock value on the depressed side of the tracks. That didn’t happen; instead, the large lots were a land bank that allowed a skyscraper boom right near the heart of a very old city, helping propel the Japanese economy beyond middle-income status. We should take a long, uncertain view of […]

In a tweet this week, the Welcoming Neighbors Network recommended that pro-housing advocates keep supply-and-demand arguments in their back pockets and emphasize simpler housing composition arguments: This advice makes an economist’s mind race. We know, after all, that supply and demand work. But we’re not so sure about composition changes. If “affordability” is achieved by building units that people don’t want (in bad locations, too small, lacking valued attributes), then the price-per-unit can be low without actually benefiting people on their own terms. Even if existing homes are bigger than many people want, at least some of the price decline from building smaller homes is the “you get what you pay for” effect. (Incidentally, this is the opposite concern from that held by econ-skeptics concerned about gentrification: they worry that new housing will be too good or that investment will upscale neighborhoods. This inverts the trope that economists “only care about money”.) A few days later, a Maryland state senator asked me that very supply-and-demand question: “What’s the evidence that large-scale upzoning leads to affordability?” This is a tough question. First, large-scale upzonings are very scarce. Second, even if one occurs, it’s not in an experimental vacuum. Three kinds of affordability Let’s specify that an upzoning likely promotes affordability in three ways: Supply and demand You get what you pay for Only pay for what you want The first channel is obvious – it explains why Cleveland is cheaper than Boston. The second source of affordability is valuable for people at risk of homelessness, but doesn’t make most people better off. The third source – what WNN recommends advocates emphasize – is that many regulations require people to pay for more housing (or pricey attributes) that they don’t want. In a lot of cases, the last two effects will go […]

As foreigners, we are mesmerized by zakkyo buildings or yokocho, but within Japan, scholars, and authorities often ignore and neglect them as urban subproducts. In spite of their conspicuous presence and popularity, the official discourse still considers most of Emergent Tokyo as unsightly, dangerous, or underdeveloped. The book offers the Japanese readership a fresh view of their own everyday life environment as a valuable social, spatial, and even aesthetic legacy from which they could envision alternative futures.

In Homelessness is a Housing Problem, Prof. Gregg Colburn and data scientist Clayton Page Aldern seek to answer the question: why is homelessness much more common in some cities than in others? They find that only two factors are significant: 1) overall rents and 2) rental vacancy rates. Where housing is scarce and rents are high, lots of people are homeless. Where rents are lower, fewer people are homeless, even in very poor places. (In fact, high city incomes correlate positively with homelessness, because more and better jobs lead to higher demand for housing). By contrast, many other factors that one might think are related to homelessness in fact are not correlated on a citywide basis. For example, since homeless people are generally poor, one might think that places with high poverty rates or high unemployment rates have lots of homelessness. The authors show that this is not the case. Where most people are poor, there is less demand for housing, which translates into lower rents and less homelessness. One might also think that places with warm weather have lots of homelessness, because homeless people might be attracted to them. But high-rent cold cities like Boston have above-average levels of homelessness, while cheaper warm-weather cities like Orlando and Charlotte do not. However, homeless people are more likely to have temporary shelter in cold cities than in expensive warm-weather cities like San Diego- either because city governments are less motivated to build homeless shelters when no one is at risk of freezing to death, or because the homeless themselves are less eager to use shelters. I suspect that if the authors focused only on highly visible unsheltered homelessness, they might have found a stronger correlation with weather). It might be argued that shelters themselves (or other social services) attract the destitute. […]

A trip to Houston reveals how a city can design without shame, urbanize around cars, and achieve privacy in a context of radical integration.

One argument against bus lanes, bicycle lanes, congestion pricing, elimination of minimum parking requirements, or indeed almost any transportation improvement that gets in the way of high-speed automobile traffic is that such changes to the status quo might make sense in the Upper West Side, but that outer borough residents need cars. This argument is based on the assumption that almost anyplace outside Manhattan or brownstone Brooklyn is roughly akin to a suburb where all but the poorest households own cars and drive them everywhere. If this was true, outer borough car ownership rates and car commuting rates would be roughly akin to the rest of the United States. But in fact, even at the outer edges of Queens and Brooklyn, a large minority of people don’t own cars, and a large majority of people do not use them regularly. For example, let’s take Forest Hills in central Queens, where I lived for my first two years in New York City. In Forest Hills, about 40 percent of households own no car. (By contrast, in Central Islip, the impoverished suburb Long Island where I teach, about 9 percent of households are car-free- a percentage similar to the national average). Moreover, most of the car owners in Forest Hills do not drive to work. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), only 28 percent of the neighborhood’s workers drive or carpool to work. Admittedly, Forest Hills is one of the more transit-oriented outer borough neighborhoods. What about the city’s so-called transit deserts, where workers rely solely on buses? One such neighborhood, a short ride from Forest Hills, is Kew Gardens Hills. In this middle-class, heavily Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, about 28 percent of households are car-free- not a majority, but again high by American or suburban standards. And even […]

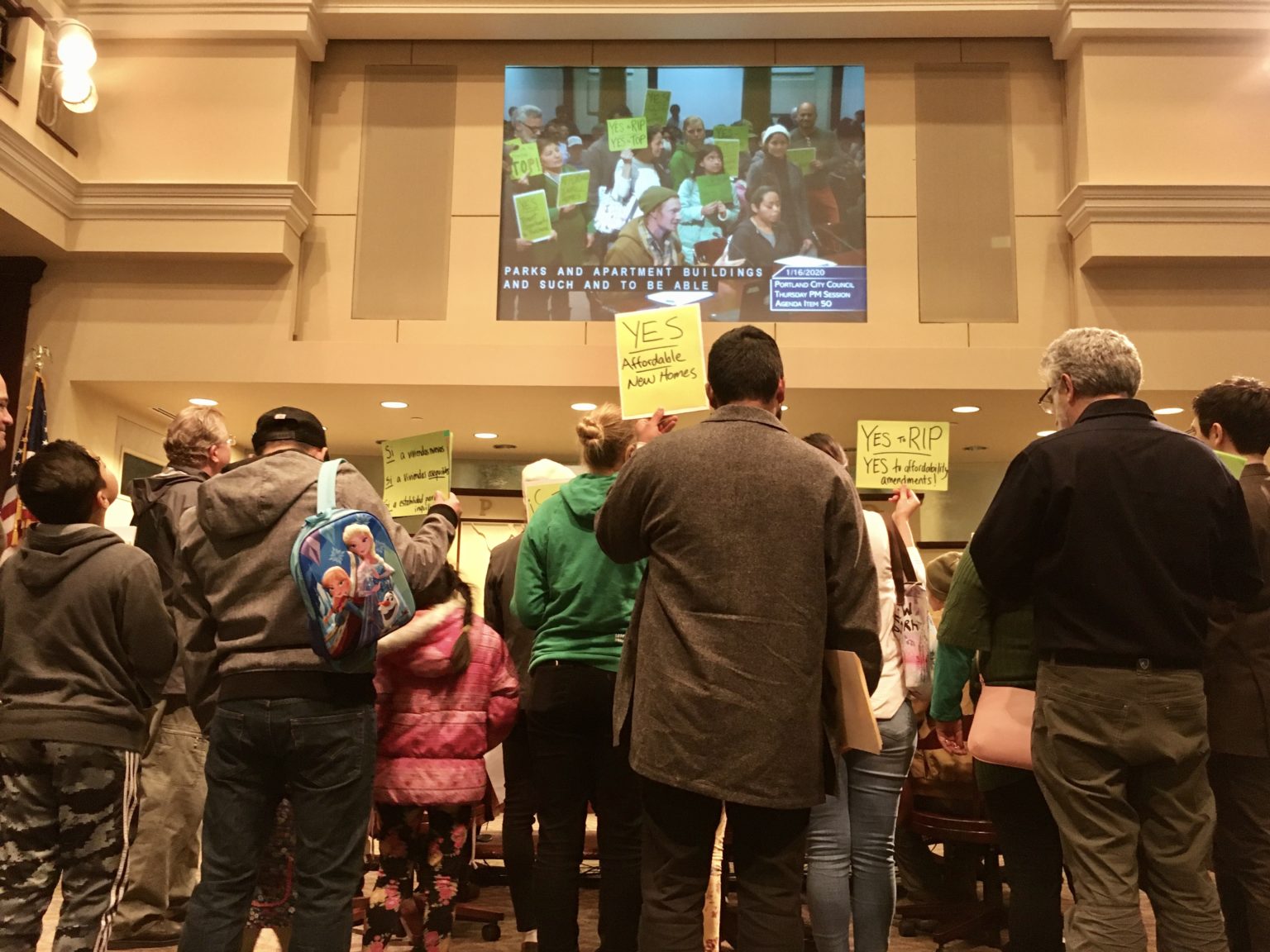

Case studies from several authors help explain the gritty politics of "Yes." The list includes three classics and will be expanded with reader submissions.

Hayek says that planning is the road to serfdom. Holland may be the most thoroughly planned country on earth - and it's delightful. How does a market urbanist respond to excellent planning?

A stickplex is a dense residential structure or group of structures built with inexpensive materials and techniques, most commonly wood. Stickplexes use 2,500 square feet of land per unit or less. Stickplexes have per-square-foot construction costs roughly in line with detached houses due to avoidance of costly features like elevators and more expensive construction methods. This type of housing includes features of both multifamily housing and single-family housing. They economize on land while avoiding the high construction costs of large multifamily buildings. Relative to high-rise housing, stickplexes can cost one-third less to build on a per-square-foot basis. And because they use a relatively small amount of land per unit, their land costs are lower than the typical detached house’s land costs. Stickplexes versus missing middle Daniel Parolek coined the term “missing middle” and emphasizes that missing middle “is compatible in scale with single-family homes.” He advises caution about permitting three-story buildings, while a stickplex can be three stories or taller. A duplex on a 6,000 square foot lot would fit the definition of missing middle. But it would not be a stickplex since it would use more than 3,000 square feet of land per unit. Missing middle housing has found traction politically. Policymakers who have passed zoning reforms from Oregon to Nebraska to Durham have used the term to describe the type of construction they would like to see. Minneapolis Council Member Lisa Goodman described the city’s reform to permit triplexes in language similar to Parolek’s: “I like to refer to it as, ‘the box can’t change,” she said. “All that can change is how many families can live within the existing box.” However, in Minneapolis, questions remain about how feasible triplexes will be to build in permitted building envelopes. Zoning rules, including floor area ratio limits of less than one […]

In two previous posts, I’ve raised questions about the competitiveness of missing middle housing. This post is more petty: I want to challenge the design rigidities that Daniel Parolek promotes in Missing Middle Housing. Although petty, it’s not irrelevant, because Parolek recommends that cities regulate to match his design goals, and such regulations could stifle some of the most successful contemporary infill growth. Parolek’s book suffers from his demands that missing middle housing match his own tastes. For instance, he has a (Western?) bias against three-story buildings. Having grown up in the Northeast, I think of three stories as the normal and appropriate height for a house. To each his own – but Parolek’s constant insistence on this point offers aid to neighborhood defenders who will be happy to quote him to make sure three-story middle housing remains missing. The house in the doghouse No form is in Parolek’s doghouse as much as the “tuck-under” townhouse, an attached house with a garage on the first floor. This is clearly a building that builders and buyers love: “If your regulations do not explicitly prohibit it, it will be what most builders will build” (p. 140). In fact, tuck-under townhouses are probably the most successful middle housing type around. In lightly-regulated Houston, builders small and large have been building townhouses, sometimes on courtyards perpendicular to the road. Parking is tucked. Townhouses are usually three stories tall (bad!), sometimes four. A few are even five stories. Their courtyards are driveways (also bad!). In a very different context – Palisades Park, NJ – tuck-under duplexes are everywhere. Their garages are excessive thanks to high parking minimums, but the form has been very successful nonetheless. These examples are not to be dismissed lightly: these are some of the only cases where widespread middle housing is […]