Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

1. Announcements: MUsings are back!! This week, we’ll get you caught up on the latest on our site and social media. Be sure to check out and share the new documentary video produced by The Institute for Humane Studies’ Josh Oldham, in collaboration with MU’s Nolan Gray and Sandy Ikeda. 2. Recently at Market Urbanism: California Legislation Threatens to Become Law and Build More Housing by Martha Ekdahl The bill, AB 2923, specifically targets the San Francisco Bay Area—making it easier than ever for the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) to build housing on the land it owns around its transit stations. Light and Air, Sound and Fury; or, Was the Equitable Life Building Panic Only About Shadows? by Nolan Gray In city after city, zoning was pitched as a way to preserve property values. And as the Federal Housing Administration marched across the country as a kind of dark Johnny Appleseed for Euclidean zoning, demanding use segregation, single-family zoning, and low densities in exchange for subsidized mortgages, the agency always defended its demands as an attempt to protect property values. Video: How Zoning Laws Are Holding Back America’s Cities by Nolan Gray It’s an understatement to say that zoning is a dry subject. But in a new video for the Institute for Humane Studies, Josh Oldham and Professor Sanford Ikeda (a regular contributor to this blog) manage to breath new life into this subject, accessibly explaining how zoning has transformed America’s cities. The Foreign Buyers Are Taking Over (Not!) by Michael Lewyn A headline in the Boston Globe screams: “Boston’s new luxury towers appear to house few local residents.” The headline is based on a report by the leftist Institute for Policy Studies, which claims that in twelve Boston condo buildings, “64 percent do not claim a residential exemption, […]

On August 23rd, a California assembly bill aimed at increasing transit-oriented development, like housing, was passed by the state senate, confirmed by the assembly, and headed to Governor Jerry Brown’s desk for signing. The bill, AB 2923, specifically targets the San Francisco Bay Area—making it easier than ever for the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) to build housing on the land it owns around its transit stations. Previously, housing developments on BART-owned land were still subject to local zoning rules, pushing projects through local processes to be approved before building began. This local control led to many delays, and, as a result, housing denials in the midst of an ongoing housing shortage—on that repeatedly spurs news headlines decrying four-plus hour super commutes, median home prices over $1 million, and neighborhoods blocking affordable housing. State bills like AB 2923 are a response to these reports, as well as the local control that led to them. If passed, AB 2923 and other bills like it, will bypass local control’s draconian rules to allow more housing to be built and ease the housing shortage. Under current law, land owned by BART is often subject to discretionary review in Bay Area cities. This forces BART to become de facto experts in every municipality zoning code, an impossible task that would take away from their focus on improving their transit system. Even attempting to master the zoning codes of every municipality takes time. Ultimately, this causes delays in building housing that’s so sorely needed. But this could easily be avoided if BART could establish their own zoning rules under AB 2923. Housing and transit is intrinsically linked and, just like suburban home developers build the roads to best suit their development, urban transit authorities like BART must utilize their capacity to build the homes best […]

On June 24 in Brooklyn, a driver in an SUV struck and killed four-year-old Luz Gonzalez, with many onlookers claiming the incident was a hit-and-run. The New York Police Department disagrees, and has refused to prosecute the driver, sparking multiple street protests. Beyond seeking justice for Gonzalez, activists demand that the city expand the use of speed cameras in school zones, which they hope could prevent further tragedy. Yet precisely at the moment that the community is most sensitive to the risk that dangerous driving poses to children, the New York state legislature shut off 140 school zone speed cameras. Given their unambiguous success in improving traffic safety in school zones, legislators should act now to renew and expand the program. While there is rare consensus among Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio on the need to preserve and even expand the traffic camera program to 290 cameras, the expansion faces opposition from some members in the Senate. Opposition to the cameras has been lead by Republican State Senator Martin J. Golden—himself a notorious school zone speeder, having received over 10 tickets since 2015 alone—and Democrat State Senator Simcha Felder, who ineffectively used the cameras as a bargaining chip to install police officers in schools. Since their implementation in 2014 as part of the broader Vision Zero initiative, school zone speed cameras have already substantially improved pedestrian safety in New York’s school zones. According to one study by the New York City Department of Transportation, the number of people killed or seriously injured in crashes in schools zones has fallen by 21 percent to 142 since the cameras came online. This is due in part to the fact that speeding drivers are getting the message: in the first 14 months following implementation of cameras, speeding violations in school […]

There’s been an ongoing debate in urbanist circles about whether autonomous vehicles (AVs) will damn us to perpetual sprawl and super commuting. I don’t believe that they will. In the first place, the business conditions under which AVs could conceivably induce more sprawl are unlikely. And in the second, there are numerous other factors that will affect the future of urban development in the US. That’s not to say we won’t double down on past mistakes, but it won’t be AVs that single handedly bring about that future on their own. No One Wants To Sell You a Self Driving Car For AVs to even begin to induce more sprawl, they need to facilitate super commuting. For that to happen at any significant scale, they need to be ubiquitous and privately owned. And that is something I don’t think we’re going to see for one simple reason — it’s a product no one is selling. Ole Muskie notwithstanding, no one with capital to burn thinks selling private AVs is a winning strategy (with good reason). Given the accumulated R&D costs of the last several years, the price a firm would need to charge for the first generation of personal AVs would be astronomical. Moreover, a company selling personal AVs would give up on mountains of valuable data generated as the vehicle racked up mileage. Trip data feeds back in to improving the ability of AVs to navigate and data about consumer habits is valuable as well. We should also remember that the state of AV technology is still quite…meh. And in the absence of a step function improvement in the technology, the fastest way to get to market is to restrict the problem space. That means means a driverless TNC service that can be limited to trips in certain areas […]

The needs of the aged are often a political football in disputes over transportation policy. On the one hand, defenders of low-cost parking and other car-oriented policies argue that older people all need cars because they can’t be bothered to walk. On the other hand, smart growth types argue that we will all be too old to drive someday, so we need to end the reign of car dependency. One way of examining the issue is to find out whether seniors in fact drive more than everyone else. Happily, the 2016 American Community Survey comes to our rescue here. In Manhattan where I live, there are just over 129,000 senior-headed households with no car, and just over 36,000 with a vehicle available. So contrary to car-lobby conventional wisdom, only about 22 percent of senior-headed households have a car. How does that compare with other age groups? On the one hand, only about 25,000 out of 200,000, or 12 percent, of millennial-headed households (that is, households headed by someone under 35) have a vehicle. But among Manhattan households headed by persons between 35 and 64, about 28 percent (just over 109,000 out of just over 386,000) have a vehicle- more than senior-headed households, to my surprise. So I rate the “Old People Need Cars” claim as Mostly False: most seniors here in Manhattan don’t have cars, even though they are more likely to own cars than millenials. On the other hand, the latter fact suggests that seniors are rarely physically incapable of using cars.

In most of my discussions of Houston here on the blog, I have always been quick to hedge that the city still subsidizes a system of quasi-private deed restrictions that control land use and that this is a bad thing. After reading Bernard Siegan’s sleeper market urbanist classic, “Land Use Without Zoning,” I am less sure of this position. Toward this end, I’d like to argue a somewhat contrarian case: subsidizing private deed restrictions, as is the case in Houston, is a good idea insomuch as it defrays resident demand for more restrictive citywide land-use controls. For those of you who haven’t read my last four or five wonky blog posts on land-use regulations in Houston (what else could you possibly be doing?), here is a quick refresher. Houston doesn’t have conventional Euclidean zoning. Residents voted it down three times. However, Houston does have standard subdivision and setback controls, which serve to reduce densities. The city also enforces high minimum parking requirements outside of downtown. On top of these standard land-use regulations, the city heavily relies on private deed restrictions. Also known as restrictive covenants, these are essentially legal agreements among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property, often set up by a developer and signed onto as a condition for buying a home in a particular neighborhood. In most cities, deed restrictions cover superfluous lifestyle preferences not already covered by zoning, including lawn maintenance and permitted architectural styles. In Houston, however, these perform most of the functions normally covered by zoning, regulating issues such as permissible land uses, minimum lot sizes, and densities. Houston’s deed restrictions are also different in that they are heavily subsidized by the city. In most cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by parties to a deed, typically organized as a […]

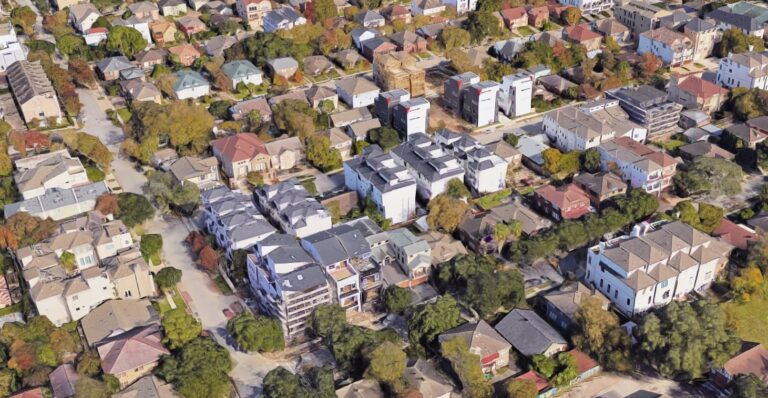

Nashville has enjoyed some of the country’s fastest job growth for several years as healthcare and tech startups have made the city home. Unsurprisingly, this economic boom has coincided with a large increase in population, greater demand for real estate, and rising house prices. But Nashville’s policy environment has moderated price increases relative to what many in-demand cities have experienced. Nashville policy has made it possible for housing developers to build both up and out in response to this new demand. However, an expansion of historic preservation efforts that have so far failed to prevent demographic change could stall the new housing supply that has maintained the city’s relative affordability. Nashville’s experience offers three lessons for other cities: 1. Legalize Housing and It Will Be Built Since 2010 the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area has grown by more than 400,000 residents, or 20 percent. Davidson County, home to Nashville at the center of the region, has grown by nearly 65,000 people, or 10 percent. Like other Southern cities, its easy to build new suburban housing in the Nashville region, and most of this population growth has been accommodated by building out. What’s unusual is that Nashville is also accommodating significant infill. In 2010 the city enacted a downtown rezoning. It eliminated parking requirements and increased by-right height limits. The new code is essentially a form-based code. Nearly all uses except for industrial are allowed in the center city. Dozens of new office, hotel, and residential towers have delivered since the new code was implemented, and many more are under construction. Since the new code has been in place, population in the two census tracts affected by upzoning has grown from about 7,500 to about 10,000. Forthcoming research from my colleague Salim Furth shows that Nashville’s recent low-density growth has been comparable to what we’d expect […]

Houston doesn’t have zoning. As I have written about previously here on the blog, this doesn’t mean nearly as much as you would think. Sure, Houston’s municipal government doesn’t segregate uses or expressly regulate densities. But as my Market Urbanism colleague Michael Lewyn has documented, city officials do regulate lot sizes, setbacks, and parking requirements. They also enforce private deed restrictions, which blanket many of the city’s residential neighborhoods. A deed restriction is a legal agreement among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property. In most cities, deed restrictions are purely private and often fairly marginal, adding rules on top of zoning that property owners must follow. But in Houston, deed restrictions do most of the heavy lifting typically covered by zoning, including delineating permissible uses and design standards. Whenever I point out that Houston has relatively light land-use regulations (and is enjoying the benefits), folks often respond that the city’s deed restrictions are basically zoning. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Before I turn to the essential differences, it’s worth first observing how Houston’s deed restrictions are like any other city’s zoning. First, like zoning, Houston’s deed restrictions are almost universally designed to prop up the values of single-family houses. Despite the weak evidence for a use segregation-property values connection, this justification for zoning goes back to the program’s roots in the 1920s. Many of Houston’s nicest residential neighborhoods, like River Oaks and Tanglewood, follow this line of thinking, enforcing tight deed restrictions on residents that come out looking a lot like zoned neighborhoods in nearby municipalities like Bellaire and Jersey Village. Second, both zoning and Houston’s deed restrictions are enforced by government officials at taxpayer expense. In most other cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by a private group like a homeowners association, […]

Market Urbanism at FEEcon 2018 Hyatt Regency Atlanta June 7-9 SPEAKERS AGENDA PRICING TRAVEL REGISTER Market Urbanism is returning to partner with the Foundation for Economic Education to present an entire track of six sessions focused on Market Urbanism at the second annual FEEcon Conference. June 7-9 2018 Wherever you live, your city uses regulations to restrict what can be built and for what purposes buildings can be used. FEEcon’s Urbanism, Development, & Your Neighborhood track is a joint effort by Market Urbanism and FEE to shed light on the vast spectrum of land use and transportation regulations that often diminish neighborhood communities, cause traffic congestion, and constrain housing supply to create affordable housing crises across the world. This track provides you with the intellectual tools you’ll need to make a case for liberty in your own backyard. https://youtu.be/RoIOi66S3PQ FEEcon is the premier gathering of freedom lovers from all walks of life, with professional networking opportunities, inspiring panel discussions, and fun for everyone – all sponsored by FEE and held at the landmark Hyatt Regency Atlanta. Choose from 50+ sessions and 8 distinct learning tracks all designed to provide real skills for professional success, combined with a solid grounding in economic, ethical and legal principles that you won’t get anywhere else. FEEcon will inspire and empower you to set your path and change the world! FEEcon will run from Thursday evening, June 7th, through Saturday evening, June 9th, 2018. All events are at the gorgeous Hyatt Regency in downtown Atlanta. Register at FEEcon.org Market Urbanism Speakers Patrik Schumacher Patrik Schumacher is partner at Zaha Hadid Architects and founding director at the AA Design Research Lab. Alain Bertaud Alain Bertaud is an urbanist and a senior research scholar at the NYU Stern Urbanization Project. Bertaud previously held the position of principal […]

Once upon a time, New York City’s poor single people were usually not homeless because they lived in little apartments with shared bathrooms and kitchens. These units are called “single room occupancy” (SRO) units in plannerese. (When I was young, people used less flattering terms such as “fleabag” and “flophouse” to describe the nastier SRO buildings). What happened? Why are so many people sleeping on the streets of Midtown? A recent paper by NYU’s Furman Center partially answers the question, by discussing the obstacles to SRO construction. For decades, New York’s housing law has made SROs almost impossible to build, in a variety of ways: By flatly outlawing SROs, unless they are built with government or nonprofit involvement Through anti-density regulations that limit the number of dwelling units in a building; Minimum parking requirements (though these are an issue primarily in the outer boroughs). The paper recommends allowing market-rate SROs, limited density deregulation, counting SRO units as affordable housing for purposes of the city’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, exempting SROs from minimum parking requirements, and government subsidies for SROs.