Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

As proposed, Moreno's 15-minute city has no chance of implementation, because economic and financial realities constrain the location of jobs, commerce, and community facilities. No planner can redesign a city by locating shops and jobs according to their own whims.

Every so often I read something like the following exchange: “City defender: if cities were more compact and walkable, people wouldn’t have to spend hours commuting in their cars and would have more free time. Suburb defender: but isn’t it true that in New York City, the city with the most public transit in the U.S., people have really long commute times because public transit takes longer?” But a recent report may support the “city defender” side of the argument. Replica HQ, a new company focused on data provision, calculated per capita travel time for residents of the fifty largest metropolitan areas. NYC came in with the lowest amount of travel time, at 88.3 minutes per day. The other metros with under 100 minutes of travel per day were car-dependent but relatively dense Western metros like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Salt Lake City and San Jose (as well as Buffalo, New Orleans and Miami). By contrast, sprawling, car-dependent Nashville was No. 1 at 140 minutes per day, followed by Birmingham, Charlotte and Atlanta. * How does this square with Census data showing that the latter metros have shorter commute times than New York? First, the Replica data focuses on overall travel time- so if you have a long commute but are able to shop close to home, you might spend less overall time traveling than a Nashville commuter who drives all over the region to shop. Second, the Replica data is per resident rather than per commuter- so if retirees and students travel less in the denser metros, this fact would be reflected in the Replica data but not Census data. *The methodology behind Replica’s estimates can be found here.

Most master plans are a costly effort by a team of temporary consultants, spread over two to three years, to prepare a blueprint that is usually obsolete as soon as it is completed.

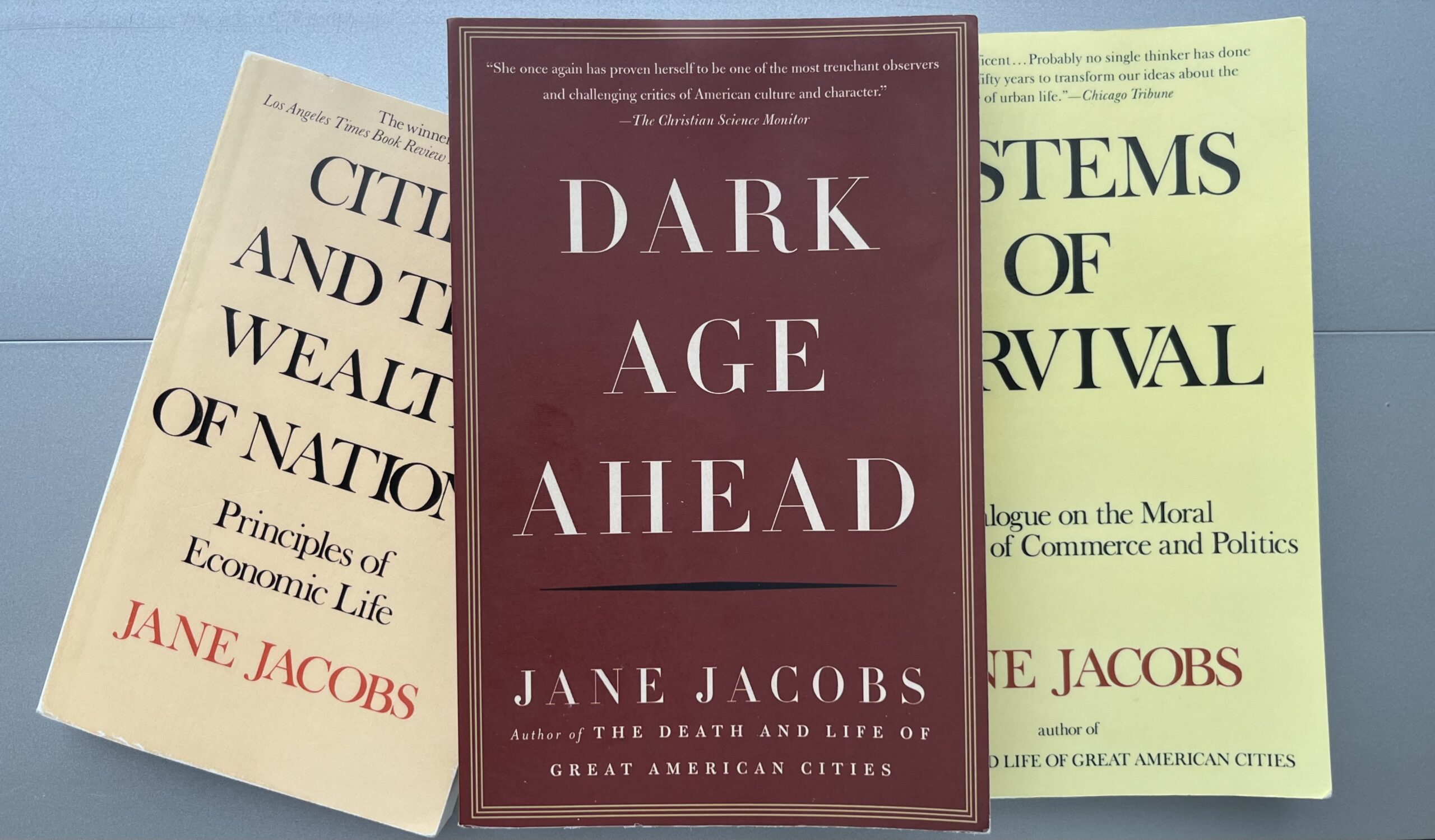

Jane Jacobs wasn’t optimistic about the future of civilisation. ‘We show signs of rushing headlong into a Dark Age,’ she declares in Dark Age Ahead, her final book published in 2004. She evidences a breakdown in family and civic life, universities which focus more on credentialling than on actually imbuing knowledge in its participants, broken feedback mechanisms in government and business, and the abandonment of science in favour of ‘pseudo-scientific’ methods. Jacobs’ prose is, as always, rich, convincing and successful in making the reader see the importance of her claims. Yet the argument that we are spiralling into a new Dark Age, similar to that which followed the fall of the Roman Empire, is not quite complete and I remain unconvinced that the areas she identified point towards collapse as opposed to merely things we could, and should, work to improve. Let us start with the idea that families are ‘rigged to fail,’ as she puts it in chapter two. Jacobs, urbanist at heart, cites ‘inhumanely long car commutes’ stemming from the disbanding of urban transit systems, rising housing costs, and a breakdown in ‘community resources’ – the result of increasingly low-dense forms of urban development – as a significant reason why families are now set up for failure. She suggests our days are filled with increasingly vacuous activities, leading to the rise of ‘sitcom families’ which ‘can and do fill isolated hours’ at the expense of ‘live friends.’ That phenomenon has now been replaced by the ‘smartphone family’ where time spent on TikTok, and consuming other forms of digital media have supplanted the ‘sitcom’ family of the past. There has been significant literature on the detrimental effects of digital technologies to our physical and mental health, not least in Jonathan Haidt’s most recent book, The Anxious Generation. A similar picture is painted by Timothy Carney in […]

Promotors of recently developed cities ranging from Nusantara, the freshly built capital of Indonesia, to Neom, Saudi Arabia’s futurist urban paradise, advertise them as breakthroughs in urban living. But does the world need new cities?

Continuing this series of book reviews on Jane Jacobs’ works, I now turn to Cities and the Wealth of Nations. But there is already a fantastic piece on the Market Urbanism website, by Matthew Robare, who reviews this book and outlines what Jacobs overlooks in her analysis. So, this piece takes a slightly different angle: inspired by (but not limited to) Jacobs’ ideas, it aims to highlight what mayors, governors and urban policymakers could do differently if they are serious about developing their cities into economic powerhouses. Here are some of the most important takeaways from this book and also how they can be expanded upon. (1) Focus on cultivating import-replacement The economies of cities do not grow out of nothing. They grow by adding productive new forms of work to old ones, by innovating, and by being cultivators of new ideas and techniques. This process of cataclysmic growth – that Jane Jacobs describes as ‘import-replacement – occurs when a city takes its existing imports and builds upon them, either improving its production through lowering costs, increasing quality, or innovating. The market for these additional goods can either be found within the city itself or serves to expand the city’s exports. These exports, in turn, bring in additional resources to either acquire additional imports or be reinvested into fuelling the processes that fuel import-replacement. Not for nothing does Jacobs describe import-replacement as a ‘cataclysmic’ process – these changes often happen over a very short period and can bring about a rapid influx of people, ideas and capital. We see this in New York City, which grew from half a million residents in 1850 to over 3.4 million at the dawn of the twentieth century. Detroit went from having 250,000 residents in 1900 to a peak of 1.8 million by 1950. […]

"These two homes straddle a 2010 zoning boundary change. The result: The house in duplex zoning converted into two homes, and the other converted into a McMansion that cost 80% more." - Arthur Gailes

Why do elevators cost so much more in America? Stephen Smith's new work breaks down the differences and points to vital reforms.

One common anti-urbanist argument is that families simply don’t want to live in cities. But analysis by New York’s Department of City Planning (DCP) also shows that prosperous parts of New York City generally added children, at least in the decade before the rise of the COVID-19 virus. DCP divided the city into “neighborhood tabulation areas” (NTAs) with population ranging from 15,000 to 100,000. DCP’s data showed that the city as a whole lost 2 percent of its under-18 population between 2010 and 2020, but that some areas had significant gains. The biggest gainers were Long Island City (over 200 percent) and four areas where the under-18 population increased by between 50 and 75 percent (the Financial District, Midtown, Midtown South, and Downtown Brooklyn). There seems to be a positive correlation between child growth and housing supply growth, even in these expensive areas. In the Long Island City NTA, the number of housing units increased by over 100 percent between 2010 and 2020- so it is no surprise that the number of children increased. Housing supply increased significantly in three of the four NTAs that added the most children. The number of number of occupied housing units increased by 23 percent in the Midtown South NTA, by 26 percent in the Financial District NTA, and by 86 percent in the Downtown Brooklyn NTA. (Central Midtown was an exception to the rule; housing supply increased more slowly there). By contrast, in Manhattan as a whole, the number of housing units increased by only 7 percent, and the number of children actually declined. Moreover, affluent areas that added very little housing supply tended to gain under-18 residents at a much slower pace. For example, in the three Upper East Side (NTAs) (Lenox Hill, Carnegie Hill, Yorkville) the number of housing units increased […]

Cities have always invited us to be constantly on the move. We move around to get to work, go shopping, meet friends, attend a concert, visit an art exhibition, and take advantage of all the many activities that a metropolis offers.