Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Is it even possible today to write a vigorous argument in favor of the urban renewal policies of the 1950s? I doubt it. Jeanne Lowe's 1967 "Cities in a Race with Time* is a sympathetic account of the urban renewal era in its own terms. How does it hold up?

Check out Alain Bertaud's Master Class lecture at CEPT University in Ahmedabad, India.

A new paper in the Journal of Development Economics by Liming Chen, Rana Hasan, Yi Jiang, and Andrii Parkhomenko estimates the welfare gains of Transit Oriented Development in Bengaluru. The Bengaluru metro or the Namma metro is around 170Km long including the planned sections. Bengaluru has low building heights and the paper’s counterfactual depends on relaxing FSI/FAR from their current level to 2 (only 2!) around 500 meters of the metro line. The paper finds “The complementarity between TOD and the metro unlocks additional gains equivalent to about $64 million per year or one-half of annual operating costs of the metro system.” Paper reference:Chen, L., Hasan, R., Jiang, Y., & Parkhomenko, A. (2024). Faster, taller, better: Transit improvements and land use policies. Journal of Development Economics, 103322.

Delete all Seattle's highways. Invent new neighborhoods. Explain macroeconomic trends with home size. Money flows uphill to water. Do NIMBYs really hate density? Urban economics is on a tear.

The conventional wisdom (based on Census estimates) seems to me that urban cores have lost population since COVID began, but are beginning to recover. But mid-decade Census estimates are often quite flawed. These estimates are basically just guesses based on complicated mathetmatical formulas, and often diverge a bit from end-of-decade Census counts. Is there another way to judge the popularity of various places? Perhaps so. I just uncovered a database of real estate price trends from Redfin. Because housing supply is often slow to respond to demand trends, housing prices probably reflect changes in demand. What do they show? First let’s look at the most expensive cities: San Francisco and New York City where I live now. If conventional wisdom is accurate, I would expect to see stagnant or declining housing prices in the city and some increase in suburbia. In Manhattan, the median sale price for condos and co-ops was actually lower in 2024 than it was in mid-2019, declining from $1.25 million in August 2019 to $1.05 million in August 2024.* Similarly, in the Bronx multifamily sale prices decreased slightly (though prices for single-family homes increased). By contrast, in suburban Westchester County, prices increased by about 30 percent (from just under 250k to 325k). Similarly, in Nassau County prices increased from 379k to 517k, an increase of well over one-third. So these prices suggest something like a classic suburban sprawl scenario: stagnant city prices, growing suburban prices. In San Francisco, by contrast, property values declined everywhere. City prices declined from $1.2 million in August 2019 to just under $1 million today; in suburban Marin County, the median price declined from $633k to $583k. So sale price data certainly supports the narrative of flight from expensive cities. What about places that are dense but not quite as expensive? But […]

In Mumbai, there is a specific type of architect who has become the interpreter of regulations and there are those architects who are aestheticians working on building skins. As much as there is convenience in this split, it has taken away a big part of the agency of the architects in the city.

Kevin Erdmann argues that mortgage credit standards are too tight. Others say the federal government is subsidizing homeownership. Can they both be right?

The goal of congestion pricing is not to penalize car trips but to smooth demand over a more extended time to reduce congestion. Unfortunately, many new congestion pricing schemes seem designed to ban cars rather than manage demand for car trips. This article appeared originally in Caos Planejado and is reprinted here with the publisher’s permission. Congestion pricing aims to reduce demand for peak-hour car trips by charging vehicles entering the city center when roads are the most congested. Charging rent for the use of roads is consistent with a fundamental principle of economics: when the price of a good or service increases, demand for it decreases. Charging different rates depending on the congestion level spreads trip demand over a longer period than the traditional peak hour. The goal of congestion pricing is not to penalize car trips but to smooth demand over a more extended time to reduce congestion. Unfortunately, many new congestion pricing schemes seem designed to ban cars rather than manage demand for car trips. Congestion pricing then becomes more akin to the “sin taxes” imposed on the consumption of tobacco and alcohol than to traffic management. The traffic on urban roads in a downtown area is not uniform during the day but is subject to rush hour peaks, while late-night road networks are usually underused. The use of roads in the downtown area is similar to other places like hotels in resort towns. Hotels try to spread demand away from peak season by reducing prices when demand is low and increasing prices when demand is high. When resort hotels charge higher prices during weekends and vacations, it is not to discourage demand but to spread demand over a broader period. Well-conceived congestion pricing for urban roads works under the same principles as the pricing of hotels. […]

A new paper proposes that increasing diversity explains 90% of the recent decline in birthrates. Lyman Stone says it's nonsense.

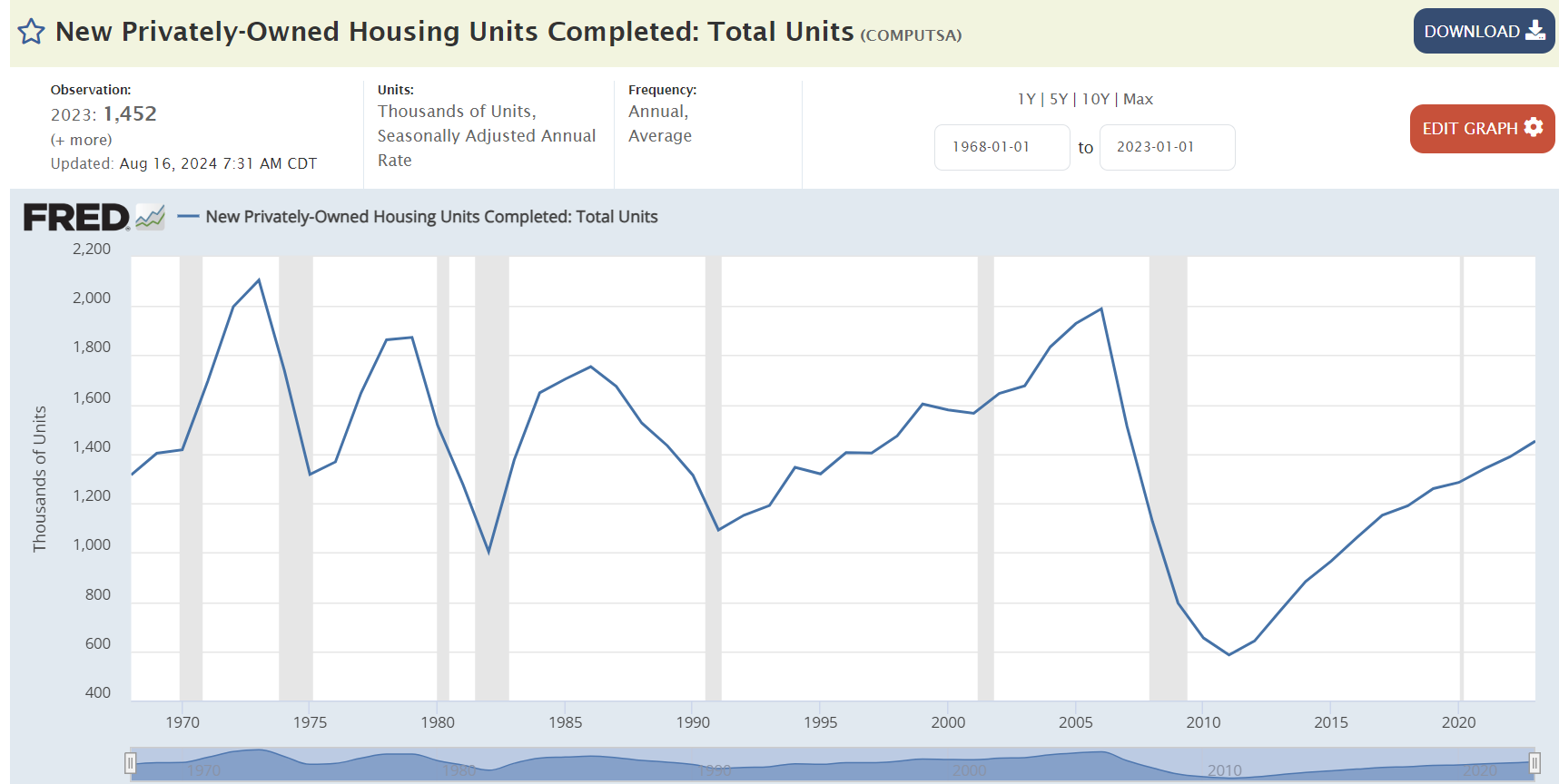

Kamala Harris has pledged to build 3 million new housing units. Setting aside the methods, what does that mean? And, would it "end America's housing shortage"?