Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Every so often I read a tweet or listserv post saying something like this: “If modern buildings were prettier there’d be less NIMBYism.” I always thought this claim was silly for the simple reason that in real-life rezoning disputes, people…

Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro has received some publicity for stating: “If you can’t afford to live here [in New York City] maybe you should not live here.” From the standpoint of advice to individuals, this statement of course makes perfect…

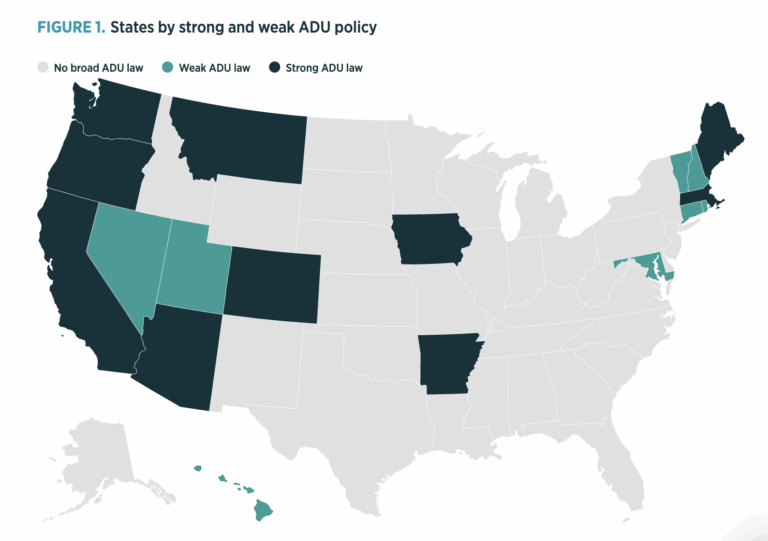

Over the past decade, state policymakers across the country have established a new, accelerating trend of state laws that set limits on local zoning authority. These laws include new requirements that localities allow more, less expensive types of housing to…

I recently saw a tweet complaining that left-wing YIMBYs favored urban containment- a strategy of limiting suburban sprawl by prohibiting new housing at the outer edge of a metropolitan area. (Portland’s urban growth boundaries, I think, are the most widely…

Via Kevin Erdmann, several Democratic and Independent U.S. senators have introduced a viciously NIMBY bill: The “Humans over Private Equity for Homeownership Act” is [would require] firms that own more than 50 single-family rental properties to divest their properties [over…

Montana passed a transformative land use reform package in 2023 – the “Montana Miracle”. This year, Montana’s legislature is again considering a lot of housing bills. The western United States overall has been the most dynamic region for pro-housing legislation,…

As a sense of urgency builds around North America’s housing affordability crisis, researchers have begun to look beyond zoning and permitting for ways to build more housing for less money. In the wake of a movement to bring more mass timber buildings to the US and Canada, some have turned their attention to the role of building codes. The first building code issue to receive sustained grassroots attention is the requirement, listed in the International Building Code (despite the name, a code mostly in use in the US), for buildings over three stories to have two exit staircases connected by a corridor. This requirement has long been in effect in most of the United States, with the exception of New York City, Seattle, and recently Honolulu and Knoxville (and a few other areas with modified versions of the requirement, as detailed in this Niskanen Center report.) Architect Sean Jursnick and developer Peter LiFari’s policy brief for Mercatus is a good general survey of the issue; for a discussion of local reforms that also interviews many of the key players, also read Patrick Sisson’s article in The Architect’s Newspaper. State legislators in Tennessee, Washington, Oregon, California, Connecticut, Virginia, and Minnesota have passed legislation directing their states’ building councils to consider – or simply approve – single-stair buildings up to six stories. Bills to similar effect were also introduced but not passed last year in New York and Pennsylvania; this year, bills are being considered in Colorado, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, and Texas. Los Angeles city councilmember Nithya Raman has also introduced a motion to update the building code there, and Austin is debating such a motion as well. Mechanisms of reform A policy brief for HUD’s Cityscape journal by Stephen Smith of the Center for Building in North […]

With state legislative seasons in full swing, a picture of the landscape of land use reform is emerging. One dynamic I’ve been tracking: Yes In God’s Back Yard (YIGBY) bills, designed to allow religious organizations (and sometimes other nonprofits) to easily use their land to build housing, are still in vogue with lawmakers. Salim Furth and I predicted last year that this year would be a key test for this policy area. While it would be a mistake to expect YIGBY to solve the housing crisis on its own, these bills can broaden the housing abundance coalition and let reluctant state lawmakers take a first step into preemption of local zoning ordinances. So far, YIGBY bills have been proposed in Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, Texas, Virginia, and Washington state. In fact, this year’s bills seem to be converging on (at least part of) the framework for YIGBY legislation that Furth and I proposed. Our framework would let organizations build to a specified development intensity everywhere, as well as to the development intensity of the surrounding neighborhood if it’s denser than that base density. Arizona’s HB 2191, for instance, specifies: B. The height requirements for an allowed use development on an eligible site must meet one of the following: 1. Be not more than thirty-eight feet and three full floors. 2. Be the maximum height allowable by the current municipal zoning regulations for retail, office, residential or mixed use. 3. be not more than the height of a previously existing structure on the eligible site. 4. be not more than the height of any existing building within one-fourth mile of the eligible site, except for buildings developed pursuant to this section. Clauses C and D set similar limits for setbacks and maximum lot coverage, followed by (emphasis mine): E. […]

A review of a book that endorses more flexible zoning, but doesn't reject zoning entirely.

In New York City, one common argument against congestion pricing (or in fact, against any policy designed to further the interests of anyone outside an automobile) is that because outer borough residents are all car-dependent suburbanites, only Manhattanites would benefit. For example, film critic John Podhoretz tweeted: “Yeah, nothing easier that taking the subway from Soundview or Gravesend or Valley Stream.” Evidently, Podhoretz thinks these three areas are indistinguishable from the outer edges of suburbia: places where everyone drives everywhere. But let’s examine the facts. Soundview is a neighborhood in the Southeast Bronx, a little over 8 miles from my apartment in Midtown Manhattan near the northern edge of the congestion pricing zone. There are three 6 train subway stops in Soundview: Elder Avenue, Morrison Avenue, and St. Lawrence Avenue. Soundview zip codes include 10472 and 10473. In zip code 10472* only 25.7 percent of workers drove or carpooled to work according to 2023 census data; 59.6 percent use a bus or subway, and the rest use other modes (including walking, cycling, taxis and telecommuting). 10473, the southern half of Soundview, is a bit more car-oriented- but even there only 45 percent of workers drive alone or carpool. 41 percent of 10473 workers use public transit- still a pretty large minority by American standards, and more than any American city outside New York. In the two zip codes combined there are just 45,131 occupied housing units, and 24,094 (or 53 percent) don’t have a vehicle. In other words, not only do most Soundview residents not drive to work, most don’t even own a car. Gravesend, at the outer edge of Brooklyn over 12 miles from my apartment, is served by three subway stops on the F train alone: Avenue P, Avenue U and Avenue X. It is also served by […]