Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Every so often I read something like the following exchange: “City defender: if cities were more compact and walkable, people wouldn’t have to spend hours commuting in their cars and would have more free time. Suburb defender: but isn’t it true that in New York City, the city with the most public transit in the U.S., people have really long commute times because public transit takes longer?” But a recent report may support the “city defender” side of the argument. Replica HQ, a new company focused on data provision, calculated per capita travel time for residents of the fifty largest metropolitan areas. NYC came in with the lowest amount of travel time, at 88.3 minutes per day. The other metros with under 100 minutes of travel per day were car-dependent but relatively dense Western metros like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Salt Lake City and San Jose (as well as Buffalo, New Orleans and Miami). By contrast, sprawling, car-dependent Nashville was No. 1 at 140 minutes per day, followed by Birmingham, Charlotte and Atlanta. * How does this square with Census data showing that the latter metros have shorter commute times than New York? First, the Replica data focuses on overall travel time- so if you have a long commute but are able to shop close to home, you might spend less overall time traveling than a Nashville commuter who drives all over the region to shop. Second, the Replica data is per resident rather than per commuter- so if retirees and students travel less in the denser metros, this fact would be reflected in the Replica data but not Census data. *The methodology behind Replica’s estimates can be found here.

One common NIMBY argument is that new development is bad because it brings traffic. As I have pointed out elsewhere, this is silly because it is a “beggar thy neighbor” argument: the traffic doesn’t go away if you block the development, it just goes somewhere else. But my argument assumed that new development would in fact bring traffic wherever it occurred. A new study by three North Carolina State University scholars suggests otherwise. The study concludes that “rural locations are more likely to experience an increase in traffic due to increased development as compared to urban land uses.” (p. 19). This is because “locations that did not experience a significant traffic increase… had a higher traffic volume before development”. (p. 20). This might be because those areas were “already highly saturated, which served as a major disincentive for the migration of traffic” (id.) So in other words, if I am understanding this paper correctly, an already-congested area will not get much more congested with new development, because people react to congestion by going elsewhere or using slightly different routes. By contrast, when a basically uncongested area gets new development, the new development does not create enough traffic to scare off drivers.

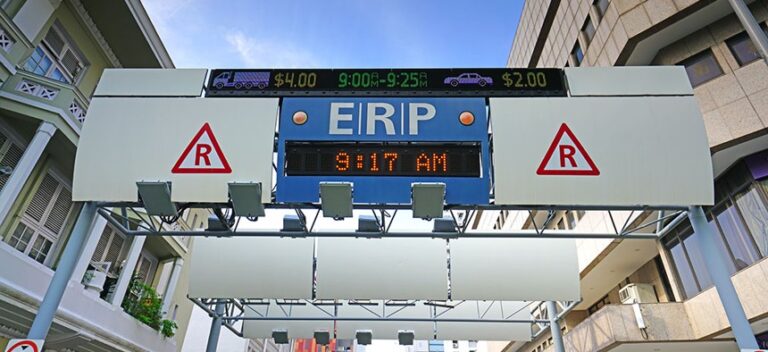

In a series of recent posts, Tyler Cowen has taken the view that congestion prices in major downtowns are a bad idea. This is what one might expect of a typical New Jerseyan, but not a typical economist. The writing in these posts is a bit squirrelly (or is it Straussian?), but as best I can make out, Tyler is deviating from the mainline economic views of externalities and prices by arguing a few points: Urban serendipity and growth are high-value externalities quite distinct from the usual efficiencies of combining large amounts of capital and labor in downtown office towers. Occasional visitors to the city find very high value there (presumably via a long-right-tail distribution) including by creating demand for new goods Congestion pricing will (a) decrease the number of people in the city, (b) particularly high-value visitors. He also makes some specific critiques of the mechanism design of the proposed NYC congestion charge. It’s worth getting that right, but let’s leave the technicalities aside here. Tyler’s points – as I’ve summarized (or mangled) them – seem like a mix of reasonable and wrong, although in several cases difficult if not impossible falsify. I’ll tackle these points in a completely irresponsible order. 2. Distinguished visitors On the second point: Diminishing marginal returns is enough to give Tyler’s argument the benefit of the doubt. The first visit to a symphony or subway likely has a bigger inspirational impact than the seventh or seven-hundredth. And outsiders may bring insights to the city in an Eli-Whitney-and-the-cotton-gin way. But for consuming new goods? Perhaps visitors’ demand is enough to sustain new imitations of low-end consumer goods (like a McDonalds in Chennai, if there is one). But for narratives of urban creativity, I prefer Malcolm Gladwell’s account of Airwalk shoes or Peter Thiel’s identification of […]

Lydia Lo and Yonah Freemark have an interesting new paper ? EditSign on zoning in Louisville on the Urban Institute website. They point out that of the land zoned for single-family housing, 59 percent is zoned R4, requiring 9000-square-foot lots, which means no more than five houses per acre. From a transportation standpoint, this is not ideal. Even the most cursory Google search reveals that a neighborhood should have at least eight or ten units per acre to support minimal bus service. This is because if only a few people live near a bus stop, only a few people will ride the bus. So Louisville’s zoning generally prohibits density high enough for decent bus service. Similarly, from a housing supply standpoint, such zoning is not ideal either. Obviously, a development with 5 houses per acre contributes less to regional housing supply than one with 10 houses per acre. Much ink has been spilled over the evils of zoning places for nothing but single-family housing. But perhaps the density of housing is just as important as its form.

What's the best urban path in America? Vote on Twitter this month for nominees in the Urban Paths World Cup.

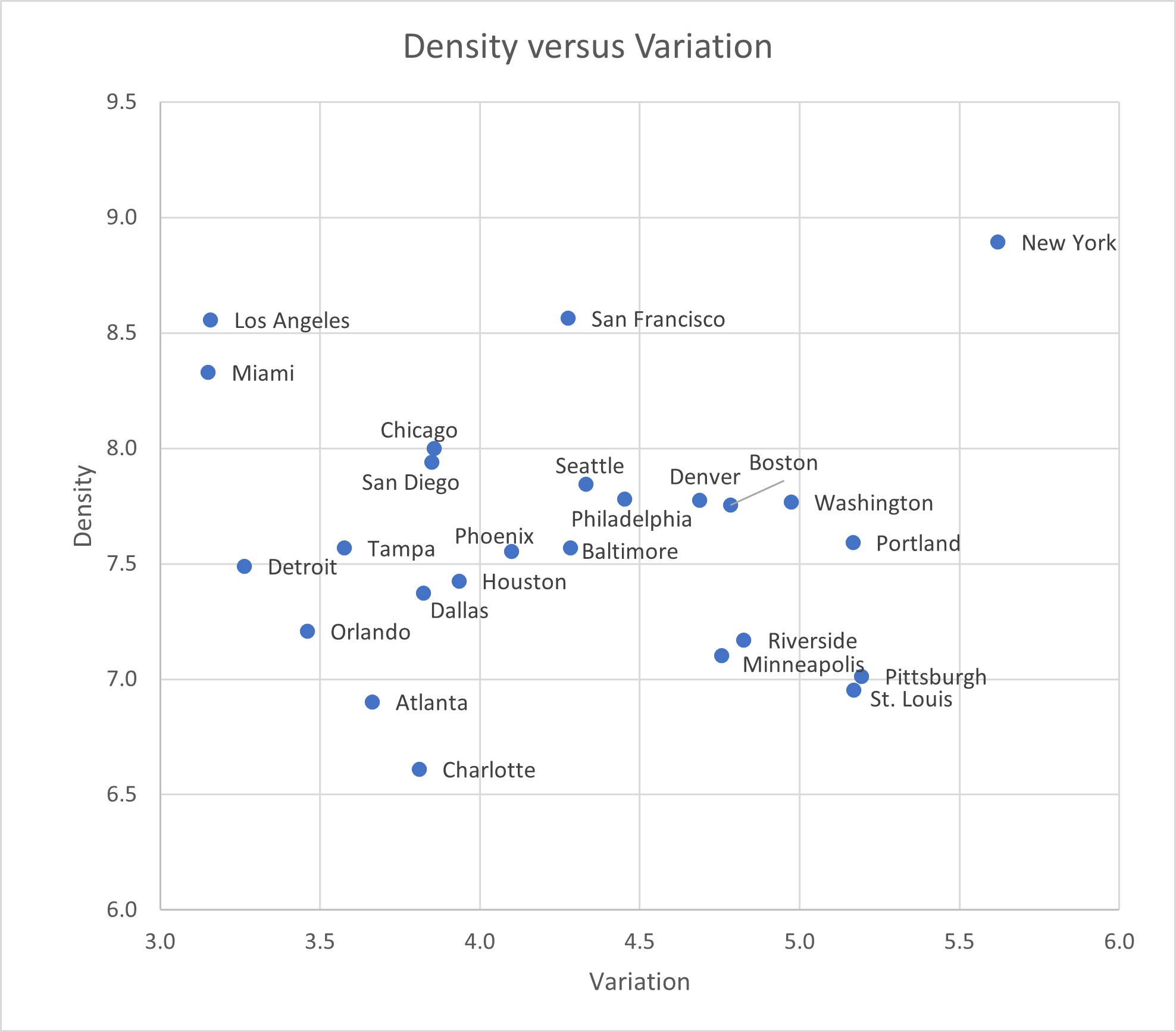

A quick data exercise shows that LA really is unique among big American metros, matched only by its East Coast twin, Miami.

One argument against bus lanes, bicycle lanes, congestion pricing, elimination of minimum parking requirements, or indeed almost any transportation improvement that gets in the way of high-speed automobile traffic is that such changes to the status quo might make sense in the Upper West Side, but that outer borough residents need cars. This argument is based on the assumption that almost anyplace outside Manhattan or brownstone Brooklyn is roughly akin to a suburb where all but the poorest households own cars and drive them everywhere. If this was true, outer borough car ownership rates and car commuting rates would be roughly akin to the rest of the United States. But in fact, even at the outer edges of Queens and Brooklyn, a large minority of people don’t own cars, and a large majority of people do not use them regularly. For example, let’s take Forest Hills in central Queens, where I lived for my first two years in New York City. In Forest Hills, about 40 percent of households own no car. (By contrast, in Central Islip, the impoverished suburb Long Island where I teach, about 9 percent of households are car-free- a percentage similar to the national average). Moreover, most of the car owners in Forest Hills do not drive to work. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), only 28 percent of the neighborhood’s workers drive or carpool to work. Admittedly, Forest Hills is one of the more transit-oriented outer borough neighborhoods. What about the city’s so-called transit deserts, where workers rely solely on buses? One such neighborhood, a short ride from Forest Hills, is Kew Gardens Hills. In this middle-class, heavily Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, about 28 percent of households are car-free- not a majority, but again high by American or suburban standards. And even […]

New York City is an epicenter of the global novel coronavirus pandemic. Through April 16, there were 1,458 confirmed cases per 100,000 residents in New York City. Always in the media eye, and larger than any other American city, New York City has become the symbol of the crisis, even as suburban counties nearby suffer higher rates of infection. In a paper dated April 13, 2020, Jeffrey E. Harris of M.I.T. claims that “New York City’s multitentacled subway system was a major disseminator – if not the principal transmission vehicle – of coronavirus infection during the initial takeoff of the massive epidemic.” Oddly, he does not go on to offer evidence in support of this claim in his paper. Conversely, as I will show, data show that local infections were negatively correlated with subway use, even when controlling for demographic data. Although this correlation study does not establish causation, it more reliably characterizes the spread of the virus than the intuitions and visual inspections that Harris relies on. Data In an ongoing crisis with a shortage of tests, all infection and mortality data come with a major asterisk: we do not fully know the extent of the data. Only when all-cause mortality data and more-extensive testing data are available can any conclusions be confirmed. This study, like Harris’ and others, is subject to potentially massive measurement error. Data from the American Community Survey (2018 5-year averages) show that commuting modes vary extensively across New York City. New York is broken into Community Districts (CDs), which generally correspond (on either a one-to-one or two-to-one basis) with Census Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs). These 55 areas contain between 110,000 and 241,000 people each. The most car-dependent PUMA (Staten Island CD3) has a car-commute share of 75%; the least car-dependent PUMA is Manhattan […]

In this interview I talk to Onésimo Flores, Founder of Jetty, a (sort-of) microtransit company from Mexico City. Marcos Schlickmann: Thank you for participating in this interview. Please introduce yourself and talk a little bit about how Jetty came to life and what is your idea behind this project. Onésimo Flores: I’m Onésimo Flores, the founder of Jetty. I have a PhD in urban planning from MIT and a master’s in public policy from Harvard. I graduated in Law from the Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico. The idea of Jetty came about by contrasting a conflicting approach to regulation in public transportation in a place like Mexico. On one end of the spectrum, a you have a very tightly-regulated, low-quality, scarce public transport service, most of it operated by private, informal, artisanal, minibus operators, and on the other hand, ride-hailing apps, taxi apps, that had emerged not only Uber but several others, that enjoy a lot of regulatory leeway in terms of freedom to set their fares, to operate anywhere, to open the market to private individuals with spare time and spare vehicles. So, in that context, the hypothesis was that, in a way applications like Uber have made it possible to standardize a level of service: people can know what to expect, know that somebody will be held accountable if something goes wrong, know the basics of the trip, the fare and the rated quality of the driver. The level of information the passengers will get is standardized no matter who the supplier of the services is. So, the hypothesis in Jetty is that we can do something similar for collective transportation without relinquishing the economies of scale of using larger vehicles, but we do give the public access to the service improvements made possible by technology. MS: Talk a little […]

Many readers of this blog know that government subsidizes driving- not just through road spending, but also through land use regulations that make walking and transit use inconvenient and dangerous. Gregory Shill, a professor at the University of Iowa College of Law, has written an excellent new paper that goes even further. Of course, Shill discusses anti-pedestrian regulations such as density limits and minimum parking requirements. But he also discusses government practices that make automobile use far more dangerous and polluting than it has to be. For example, environmental regulations focus on tailpipe emissions, but ignore environmental harm caused by roadbuilding and the automobile manufacturing process. Vehicle safety regulations make cars safer, but American crashworthiness regulations do not consider the safety of pedestrians in automobile/pedestrian crashes. Speeding laws allow very high speeds and are rarely enforced. If you don’t want to read the 100-page article, a more detailed discussion is at Streetsblog.