Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

I am arguing on Twitter about whether New York City (where I live) could really build a significant amount of new housing if zoning was less restrictive. One possible argument runs something like this: “New York is so built out…

I recently saw a tweet complaining that left-wing YIMBYs favored urban containment- a strategy of limiting suburban sprawl by prohibiting new housing at the outer edge of a metropolitan area. (Portland’s urban growth boundaries, I think, are the most widely…

walkable suburbs have as many children as more typical suburbs

Every so often I read something like the following exchange: “City defender: if cities were more compact and walkable, people wouldn’t have to spend hours commuting in their cars and would have more free time. Suburb defender: but isn’t it true that in New York City, the city with the most public transit in the U.S., people have really long commute times because public transit takes longer?” But a recent report may support the “city defender” side of the argument. Replica HQ, a new company focused on data provision, calculated per capita travel time for residents of the fifty largest metropolitan areas. NYC came in with the lowest amount of travel time, at 88.3 minutes per day. The other metros with under 100 minutes of travel per day were car-dependent but relatively dense Western metros like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Salt Lake City and San Jose (as well as Buffalo, New Orleans and Miami). By contrast, sprawling, car-dependent Nashville was No. 1 at 140 minutes per day, followed by Birmingham, Charlotte and Atlanta. * How does this square with Census data showing that the latter metros have shorter commute times than New York? First, the Replica data focuses on overall travel time- so if you have a long commute but are able to shop close to home, you might spend less overall time traveling than a Nashville commuter who drives all over the region to shop. Second, the Replica data is per resident rather than per commuter- so if retirees and students travel less in the denser metros, this fact would be reflected in the Replica data but not Census data. *The methodology behind Replica’s estimates can be found here.

NYU professor Arpit Gupta has channeled the annoyance of economists into a blog post directly calling out the Strong Towns "growth Ponzi scheme" line of argument.

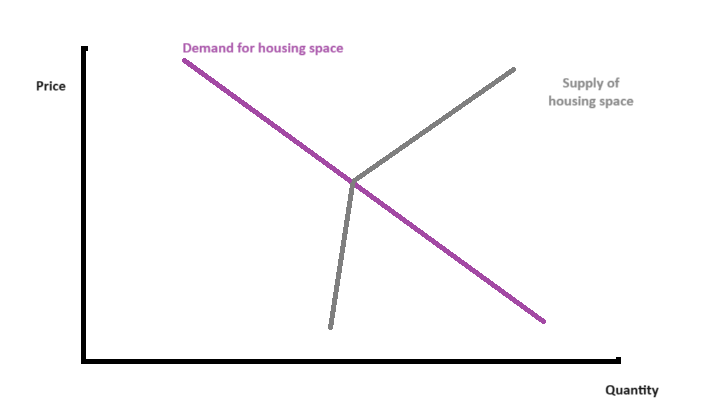

Should YIMBYs support or oppose greenfield growth? Two basic values animate most YIMBYs: housing affordability and urbanism. Sprawl puts those values into tension. Let’s take as a given that sprawl is “bad” urbanism, mediocre at best. Realistically, it’s rarely going to be transit-oriented, highly walkable, or architecturally profound. So the question is whether outward, greenfield growth is necessary to achieve affordability. And the answer from urban economics is yes. You can’t get far in making a city affordable without letting it grow outward. Model 1: All hands on deck Let’s start with a nonspatial model where people demand housing space and it’s provided by both existing and new housing. Existing housing doesn’t easily disappear, so the supply curve is kinked. A citywide supply curve is the sum of a million little property-level supply curves. We can split it into two groups: infill and greenfield, which we add horizontally. If demand rises to the new purple line, you can see that the equilibrium point where both infill & greenfield are active is at a lower price & higher quantity than the infill-only line. The only way to get some infill growth to replace some greenfield growth, in this model, is to raise the overall price level. And even then, the replacement is less than 1-for-1. Of course, this is just a core YIMBY idea reversed! In most U.S. cities, greenfield growth has been allowed and infill growth sharply constrained, so that prices are higher, total growth is lower, and greenfield growth is higher than if infill were also allowed. At the most basic level, greenfield growth is simply one of the ways to meet demand. With fewer pumps working, you’ll drain less of the flood. Model 2: Paying for what you demolish Now let’s look at a spatial model where people […]

Aaron Renn has an interesting article in Governing. He suggests that even though urban cores are responsible for a significant chunk of the regional tax base, “[t]he city is dependent on the suburbs, too.” In particular, he notes that downtowns are dependent on a labor and consumer pool that extends far beyond downtown. For example, Manhattan is valuable because it is at the center of a vast region. He’s right- if you define “suburb” broadly as “everything that isn’t downtown.” A downtown that isn’t surrounded by neighborhoods is just a small downtown. But that isn’t always the way Americans understand suburbs. If you think of suburbs as “towns outside the city with a different tax base that are usually much richer than the city” , suburbs aren’t good for the city at all. Because of the growth of suburbs, cities have stunted tax bases because they have a disproportionate share of the region’s poverty, and have to pay for a disproportionate share of poverty-related government programs. By contrast, if cities resembled the cities of 100 years ago that included nearly all of their regional population, they would have stronger tax bases. (This may seem like a pipe dream to residents of northeastern cities trapped within their 1950 borders, but plenty of Sun Belt cities include huge amounts of suburb-like territory). Similarly, if you think of suburbs as “places where most people have to drive to get anywhere” their existence is not so good for the city. When suburbanites drive into the city they create pollution, and they lobby for highways that make it easier for them to create even more (while taking up land that city residents would otherwise use for businesses and housing). And when jobs move to car-dependent suburbs, that devalues city living, either because carless city residents […]

During the Trump Administration, liberals sometimes criticized conservatives for being anti-anti-Trump: that is, not directly championing Trump’s more obnoxious behaviour, but devoting their energies to criticizing people who criticized him. Similarly, I’ve seen some articles recently that were anti-anti-NIMBY*: they acknowledge the need for new housing, but they try to split the difference by focusing their fire on YIMBYs.** A recent article in Governing, by Aaron Renn, is an example of this genre. Renn agrees with “building more densely in popular areas like San Francisco and the north side of Chicago, in other cities along commercial corridors, near commuter rail stops, and in suburban town centers.” Since I am all for these things, I suspect I agree with Renn far more than I disagree. But then he complains that YIMBYs “have much bigger aims” because they “want to totally eliminate any housing for exclusively single-family districts- everywhere.” What’s wrong with that? First, he says (correctly) that this would require state preemption of local zoning. And this is bad, he says, because it “would completely upend this country’s traditional approach to land use.” Here, Renn is overlooking most of American history: zoning didn’t exist for roughly the first century and a half of American history, and in some places has become far more restrictive over the last few decades. Thus, YIMBY policies are not a upending of tradition, but a return to a tradition that was destroyed in the middle and late 20th century. To the extent state preemption gives Americans more rights to build more type of housing, it would actually recreate the earlier tradition that was wiped out. Moreover, even if the status quo was a “tradition”, that doesn’t make it the best policy for the 21st century. For most of the 20th century, housing was far cheaper than […]

American YIMBYs point to Tokyo as proof that nationalized zoning and a laissez faire building culture can protect affordability. But a great deal of that knowledge can be traced back to a classic 2014 Urban Kchoze blog post. As the YIMBY movement matures, it's time to go books deep into the fascinating details of Japan's land use institutions.

Over the past week, the press was chock full of 2020-style headlines like “Census Bureau Confirms Pandemic Exodus from SF.” That’s because according to the Census Bureau, virtually every urban county in the U.S. (even urban counties in growing metros like Dallas and Atlanta) lost population between July 2020 and July 2021. But is the hype justified? I suspect not, for a variety of reasons. First of all, Census Department estimates have, in recent years, tended to underestimate urban populations, at least in some cities. For example, in 2019 the Census estimated Manhattan’s population as 1.628 million, while the actual count of 2020 showed 1.694 million residents- an underestimation of over 65,000 people. The Census estimated Brooklyn’s population at 2.559 million, but the actual count showed 2.736 million- an underestimate of over 150,000. (On the other hand, the 2020 population count was actually a bit lower than the 2019 estimates for Washington and San Francisco). Second, even the 2020 Census probably undercounted cities more than it undercounted suburbs. How do we know this? Because according to the Census Bureau itself, it undercounted Blacks by 3 percent and Hispanics by 5 percent, while slightly overcounting whites. These groups tend to be more urban than suburban (at least compared to whites) – so if the Census undercounted these groups, it probably undercounted urban population generally. Third, the timing of the Census Bureau’s estimates does not quite make sense to me. By July 2021, rents had already began to rise in Manhattan; the low rents of February and March were already disappearing. This suggests that by July, population (and thus demand) was increasing. Fourth, even if the Census Bureau’s population estimates were valid for the summer of 2021, they certainly aren’t valid any more. How do we know? It seems pretty obvious that […]