Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

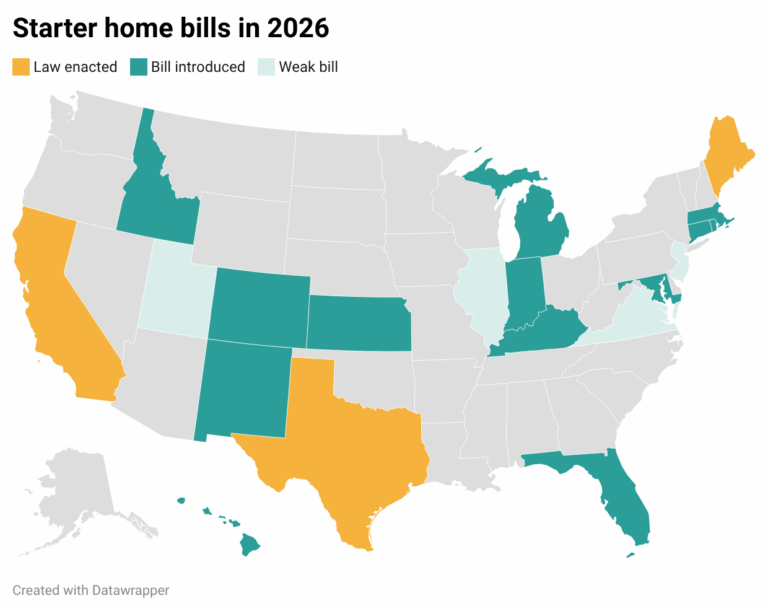

Updated 2/19 to add Michigan, 2/17 to add Kentucky, 2/16 to add Idaho, 2/11 to add Connecticut; 2/5 to add Colorado; and 1/30 to add Hawaii, Kansas, New Mexico, and Rhode Island. After decades of background study and advocacy –…

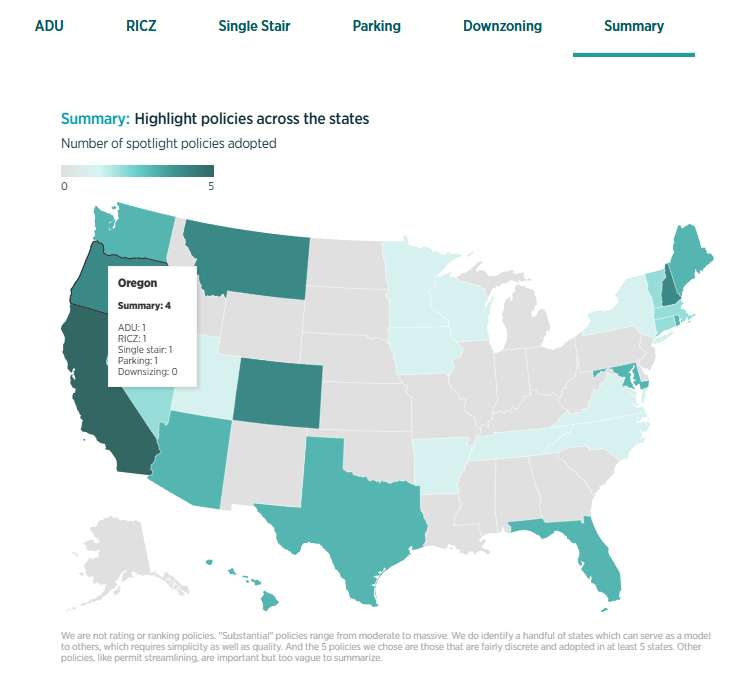

With a hugely productive legislative season in 2025, pro-homes legislators are rapidly taking good ideas around the country. To keep track of it all, my team created a new set of interactive maps. You can see snapshots here: Our goal…

In Chapters 2 and 3, Ellsworth tries to argue for supply skepticism- that is, the idea that new housing (or at least the high-end towers that she opposes)* will not reduce rents or housing costs. She has made some effort…

Every so often I read a ringing defense of anti-housing, anti-development politics. Someone on my new urbanist listserv recommended an article by Lynn Ellsworth, a homeowner in one of New York’s rich neighborhoods who has devoted her life to (as she…

Here are the results of my first use of OpenAI’s Deep Research tool. I asked for information that I know well – and in which inaccurate research has been published. It did a great job and relied substantially on my…

A review of a book that endorses more flexible zoning, but doesn't reject zoning entirely.

In recent years, three states have legalized or decriminalized jaywalking: Virginia and Nevada did so in early 2021, and California legalized jaywalking at the start of 2023. The traditional argument for anti-jaywalking laws is that they protect pedestrians from themselves, by limiting their ability to walk in dangerous traffic conditions. If this argument made sense, we would have seen pedestrian traffic fatalities increase in less punitive states. For example, if jaywalking laws were effective, California’s pedestrian death rate would have increased in 2023 (when jaywalking was legalized). Instead, the number of deaths decreased from 1208 to 1057, a 12 percent drop. (Relevant data for all states is here). Although pedestrian deaths decreased nationally, the national decrease was only about 5 percent (from 7737 to 7318). On the other hand. the data from Nevada and Virginia is less encouraging. As noted above, jaywalking was decriminalized in those states in 2021, so the relevant time frame is 2021-23. During this period, pedestrian deaths increased quite modestly in Virginia (from 125 to 133) and more significantly in Nevada (from 84 to 109). On balance, it does not seem that there is a strong trend in either direction in these three states- which (to me) supports my previously expressed view that Americans should be trusted to walk where they like rather than being harassed by the Nanny State.

Thanks to local journalist Margaret Barthel for finding and posting the elusive judicial decision that has struck down Arlington, Virginia's, missing middle ordinance, pending appeal.

As anticipated by the “radical agreement” among the parties and justices at oral argument, the Supreme Court’s recently released decision in Sheetz v. County of El Dorado put to rest the question of whether legislatively-imposed land use permit conditions are outside the scope of the takings clause. The unanimous ruling confirms the common-sense proposition that a state action cannot evade constitutional scrutiny simply because it’s a law of general application rather than an administrative decree, and subjects conditions on building permits – whether monetary or not – to the essential nexus and rough proportionality requirements enshrined in the Nollan and Dolan cases. The narrow ruling reflects the sound principle that, when dealing with constitutional questions, a court shouldn’t address hypotheticals or other issues not in direct contention among the parties. Nonetheless, the majority felt compelled to state that it would not address “whether a permit condition imposed on a class of properties must be tailored with the same degree of specificity as a permit condition that targets a particular development,” which seems to leave open the possibility that the answer might be “no.” Justice Gorsuch, in his concurrence, was astonished by this statement, wondering how a court which had just endorsed the universal applicability of the takings clause could stumble into another arbitrary distinction with no basis in common sense or constitutional law. The court’s concern was not a jurisprudential one, but apparently a policy one: in another concurrence, Justices Kavanaugh, Kagan and Jackson note that “[i]mportantly, therefore, today’s decision does not address or prohibit the common government practice of imposing permit conditions, such as impact fees, on new developments . . . .” The justices’ impression that applying the current Nollan/Dolan formula to impact fees would or even could “prohibit” them is unfounded. As Emily Hamilton and I wrote […]

Just 1 in 25 new apartments is owner-occupied. What happened to building condos?