Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

A problem that pro-housing YIMBYs face in communities nationwide is that the NIMBYs opposing them are much better organized. The reason boils down to the classic problem of concentrated costs and dispersed benefits: the beneficiaries of new housing are scattered, while those who benefit from a housing shortage–and thus higher prices–are concentrated. These organizational skills enable NIMBYs to dominate the discussion, something evident after the recent rejection of a development project in Ardsley, New York. The Jefferson Development Group wanted to build the Saw Mill River project, a development that would include 272 apartments in downtown Ardsley on land now owned by the chemical company Akzo Nobel. During a February hearing for the development, 30 people spoke against it while none spoke in favor. A petition against the project got 1,300 signatures, and houses and streets were adorned with signs reading “STOP THE JEFFERSON.” A blog with that title was also made. As a consequence, Akzo Nobel cancelled its contract to sell the property to Jefferson because they lost confidence that the property would be rezoned from industrial to mixed-use commercial and residential. One complaint was that the project would cause excess traffic. Ardsley, which is an affluent suburb just north of The Bronx, has narrow roads compared to other suburbs in Westchester County. Local developer and placemaker Padriac Steinschneider noted that traffic lights retard the flow of automobiles. The pre-programmed delays impede people, but they do not improve safety because drivers rely on the color of the light more than their own senses. He suggested that replacing traffic lights with stop signs, which force drivers to be alert, would speed traffic in Ardsley. He also discussed how Addyman Square, a towncenter featuring several restaurants and shops, could be made more pedestrian friendly if it was redesigned as a roundabout, […]

This month marks the 100th anniversary of two pieces of legislation that revolutionized the way we live. On July 11, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the first Federal Aid Road Bill. And on July 25, 1916–exactly 100 years ago today–New York City passed the country’s first comprehensive zoning ordinance. Prior to 1916, transportation infrastructure was primarily a local and/or private responsibility. For example, cities leased their rights-of-way to trolley companies, which operated transit lines. Railroad companies provided travel service between cities. The 1916 Federal Road Bill was the first step in nationalizing transportation infrastructure funding, with the state highway departments formed to manage federal appropriations for roads. These two pieces of legislation produced radical change, as government favoritism of automotive infrastructure crowded out other transportation modes and undermined innovation. In the century prior to 1916, entrepreneurs invented steam ferries, trains, bicycles, trolleys, and automobiles. Such advances ceased after 1916. Yes, today’s cars are more comfortable and powerful, but they have the same steering wheel, four tires, and internal combustion engine as the Model-T Henry Ford was building 100 years ago. As for roads, the main difference is they are bigger. Unable to compete with government favored automobiles, Charleston’s last private ferry operator closed shop in 1930. Its trolley lines, which carried 20 million passengers/year (compared with CARTA’s 5 million/year) stopped running in 1937. Zoning is segregation – not only of land uses deemed incompatible, but of people deemed “undesirable.” Progressives behind New York City’s 1916 zoning ordinance regarded immigrants moving into northern cities from Europe and the South as “undesirable.” In 1921, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover tapped Edward Bassett, the leading advocate of New York City’s 1916 zoning, to create a model zoning ordinance. Engineer Morris Knowles also served on this committee. In its 1926 landmark decision in Euclid v. […]

Tech for Housing was founded to organize Bay Area tech workers around supply friendly land use reform. Tony Albert, Joey Hiller and myself, all saw an unmet need for tech-centric political outreach and decided to try our luck. And as tech workers ourselves, we had certain ideas around the best ways to self-organize and why that organization hadn’t really happened to date. One problem with mobilizing Bay Area tech, we realized, is that many of us spend 50-60 hours a week at work. For those of us that weren’t already passionate about land use issues (yes, I’m aware I just used the terms ‘passionate’ and ‘land use’ in the same sentence), spending significant time and energy to understand, let alone act on, reform is asking a lot. We also noted that tech workers are, to varying degrees, transplants. Consequently, the existing political infrastructure that’s not too great at mobilizing tech workers generally is even less effective at activating recent arrivals who might not even be registered to vote in their new jurisdiction. After thinking through these and other reasons that we in tech remain politically apathetic, we realized the challenge was to dramatically increase the perceived benefit and decrease the perceived cost of political participation. To that end, we’ve started with tech focused content on housing policy, explaining at a high level 1) what’s broken, 2) why it’s broken and 3) what can be done about it. A lot of what’s happening at this stage is attracting the other workers in our industry who are already wonky enough to have read How Burrowing Owls Lead to Vomiting Anarchists two or three times. And after developing that core audience, providing them ways to activate our less engaged colleagues via various forms of social signaling. There’ll only ever be a certain number of people […]

Commercialism is blamed for most of the evils that plague society, inside and out of India. In the Indian city of Coimbatore, roads have become narrower and traffic more intense. There is not enough space for pedestrians. Many residents blame the city’s rising level of commercialization. Are these people correct? If they were, the world’s most commercial cities would be the least livable. But anyone with a modicum of education or travel experience knows this is not true. The cities with the most economic freedom, commercial enterprise and prosperity–think Hong Kong, Singapore, London, Sydney and Vancouver–also have the highest living standards. Similar studies show that the cities with the lowest living standards, meanwhile, are in countries that are developing, or that are suffering under repressive, anti-capitalist regimes (think Caracas, Venezuela, the world’s most dangerous city). Nevertheless, it is clear that the most commercialized Indian cities have become less livable in some important ways, such as by suffering from more congestion. So, what is going on? It is true that people migrate to cities with more commercial enterprise. It may seem that such “crowding” is unpleasant. But people are migrating to these cities precisely because there are more shops, hospitals, schools, leisure spaces and other amenities. The fact that there is already a heavy concentration of people in these cities is an important factor also, since that means there are more potential employers and business associates. Alas, the existence of people somewhere lures yet more people. Indeed, it is hard to think of a neighborhood where real estate prices have significantly fallen because of population growth. Such neighborhoods may have become more crowded…but that does not mean they are less livable. Moreover, vast population growth and crowding are not the same. Population density is defined as the number of people living on […]

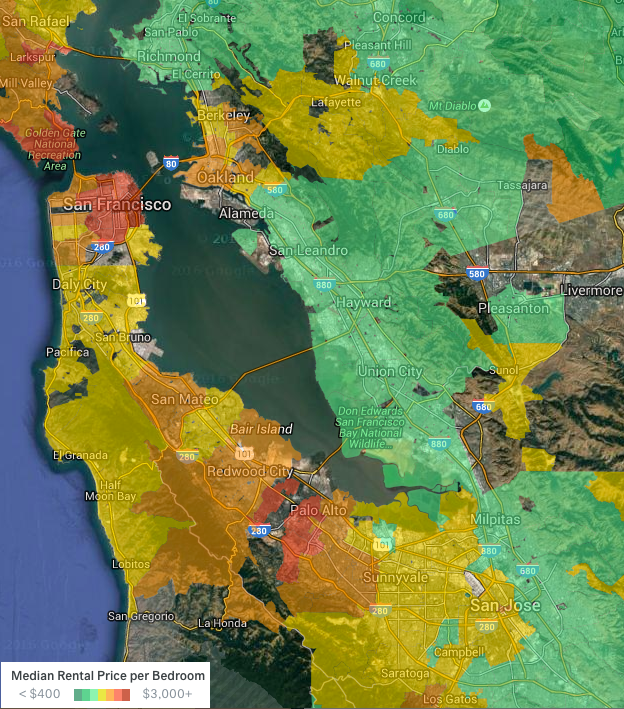

[Editor’s note–this is the inaugural article for a new blog that Jeff launched called Tech For Housing, where tech workers advocate for more housing in the Bay Area.] San Francisco–For decades, every city in the Bay Area has restricted housing production. And for decades, the Bay Area has gone deeper into housing debt. People and money continue streaming into the region, cities rarely allow new housing, and prices continue to rise. This hurts every industry in the Bay Area, and tech is no exception. The housing market steals money straight out of our pockets and, if we stay the current course, will rob us of the better version of ourselves we need more time to become. How Housing Robs Us Blind Housing in San Francisco costs 73% more than in Austin, 53% more than in Seattle, and 36% more than in Los Angeles. And figures for many of the Peninsula Cities are even worse. After accounting for cost of living, our real incomes in Bay Area tech are often lower than those of our colleagues in less expensive locales simply by virtue of housing costs. Obviously, this is bad for us as employees, but it hurts founders and investors as well. The higher housing prices climb, the more founders have to pay employees to provide for the same standard of living. And the higher labor costs become, the more money founders have to raise from investors, meaning more capital gets tied up funding the same amount of work. All this adds up to tech, as an industry, paying more and more to stay in the Bay Area for zero added benefit. Median Rental Price per Bedroom Source: Trulia But there’s more at stake than just burn rates and take-home pay. As it stands, housing prices are a millstone around our […]

One common argument against building new housing is that new construction will never reduce housing costs, because the influx of ultra-rich people into high-cost cities creates an insatiable level of demand. I recently found a source of information that may be relevant to this argument: the Wealth Report, which lists the number of high-wealth individuals in a set of world cities, including five American cities (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston and Miami). In particular, the report lists the number and percentage growth of “ultra high net worth individuals” (UHNWIs), which it defines as those with over $30 million in wealth. It seems to me that if UHNWI growth was related to high housing costs, then the most expensive cities in this group (New York and Los Angeles) would have the highest UNHWI growth. In fact, the number of UHNWIs grew most rapidly in Houston (63 percent) between 2005 and 2015. By contrast, UNHWI growth in the other four cities ranged between 31 and 34 percent. In Canada, UNHWI growth was higher, but roughly equal (ranging between 65 and 70 percent) in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal- despite the fact that these cities have radically varying housing costs. The median housing unit price in Vancouver tops $1 million, about three times the median price in Montreal. What about UNHWIs as a percentage of city population? New York has 5600 of them in a city of 8.1 million*- just under 700 per 1 million. Low-cost Chicago has 2030 in a city of 2.7 million- about 750 per 1 million. Houston has 1318 in a city of 2.1 million, or around 625 per million. These differences don’t strike me as significant. *I am assuming these people all live in the central city; I am not actually sure this is the case, […]

[Research help for this article was provided by UCLA student Mitchell Boswell] The past 15 years have seen a hell of a lot of gentrification in LA. 15% of our poor neighborhoods have undergone gentrification since the year 2000, and it feels like things have only accelerated since the end of the financial crisis. That’s putting a huge strain on communities across the city, from Boyle Heights to Leimert Park. But before we get into why, let’s get one thing out of the way… Academics love to debate about whether gentrification is good or bad for residents of poor neighborhoods. Maybe we should try listening to what people actually want. Some argue that when a neighborhood gentrifies, more of the existing residents stay in the neighborhood than they otherwise would (one of the many, many hard things about poverty is housing insecurity, so folks tend to move around a lot no matter what), and also tend to be more satisfied after the change. On the other side of the debate are people arguing that as gentrification occurs, the investment and new residents push up rent prices and drive out poor residents who made that community home. It’s not clear who’s right. That all seems pretty academic – it’s an argument between folks who are well-off about whether or not people in poor neighborhoods should be happy. Instead of telling people how they should feel, maybe we should stop and listen, just for a minute, to what they want. And a lot of those people sure as hell don’t seem to want gentrification. The lack of new housing on the Westside is driving gentrification There are a lot of reasons for gentrification, but the lack of new housing on the Westside deserves a lot of the blame in recent years. As […]

One common argument against allowing the construction of taller apartment buildings is that tall buildings cost more to build, and thus are “overwhelmingly occupied by the wealthy.” For example, tall buildings, unlike houses and walk-up buildings, require elevators. But in fact, fairly tall buildings can be pretty cheap where demand is low and/or housing supply is high. For example, in East Cleveland, a low-income suburb of Cleveland, one 24-story building rents one bedroom apartments for as little as $552 per month, despite the fact that the building contains extras such as a pool and a fitness center. This means that (assuming rent should be no more than a quarter of income) someone earning less than $30,000 could afford this building. Even in nicer neighborhoods, older high-rises are not hugely expensive: for example, in midtown Atlanta, the Darlington’s apartments start at just over $700. It could be argued that because these buildings were built decades ago, their costs are not relevant to those of newer buildings. Certainly, newer high-rises are more expensive than older ones- but the same is true for newer walk-ups. To test this proposition, I focused on the outer boroughs of New York, using Zillow.com to focus on buildings built between 2010 and 2016. The cheapest newer apartment in Brooklyn started at $1150 (about $350 more than the cheapest older listing); the cheapest new elevator building started at $1600 (and included a doorman, thus inflating the rent beyond the basic amount caused by elevators). Similarly, in Queens the cheapest newer building rented for $1450 (over $600 more than the cheapest older listing), while the cheapest newer elevator building rented for $1550. In sum, it seems to me that the difference in cost between the cheapest high-rises and the cheapest low-rises, although not nonexistent, are not huge either.

On Thursday, the Massachusetts State Senate voted 23-15 to pass the zoning reform bill, S.2311, after approximately three hours of debate and amendments. 20 of the 63 amendments were adopted, with the rest either defeated or withdrawn. According to the Massachusetts Smart Growth Coalition, the bill directs municipalities to allow accessory dwelling units as-of-right in single-family residential districts; permits more as-of-right multifamily housing; reduces the number of votes needed to change zoning from a two-thirds majority to a simple majority; allows development impact fees; eliminates the need for special permits for some types of zoning; provides standards for granting zoning variances; establishes a training program for zoning board members; and lastly, modifies the process of creating a subdivision. One amendment that was defeated, proposed by Sen. William Brownsberger, removed a provision that would have required cities with an inclusionary zoning policy to offer concessions such as density bonuses. A provision from the first Senate version of the bill, S. 122, that would have allowed for consolidated permitting, was not enacted. Unlike past ones, this bill actually has teeth: the as-of-right multifamily provision establishes a minimum density of 8 units per acre for rural communities and 15 for others and if municipalities don’t comply, courts can provide relief. The bill was passed despite last-minute attempts to derail it by Sen. Bruce Tarr (R-Essex and Middlesex), who attempted to have it sent back to the Ways and Means Committee on the grounds that it had no public hearings since last September. This was rejected by the other senators, with Sen. Dan Wolf (D-Barnstable) saying he wished every bill was as fully vetted as S.2311. “We have fully vetted this, we are ready to move,” he said. “We need to update outdated zoning laws,” said Sen. Harriette Chandler (D-Worcester). “To recommit will serve nothing but […]

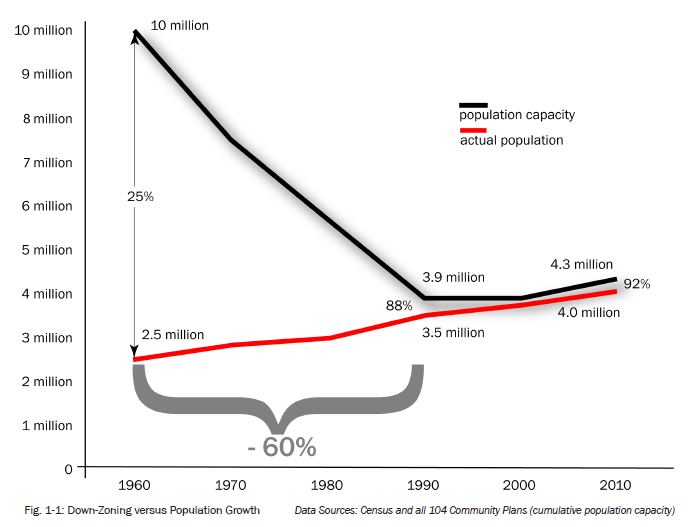

In 1986, a foreshadowing of today’s fight over “neighborhood integrity” was taking place, culminating in November as Los Angeles residents voted 2-to-1 to cut the development potential of thousands of parcels across the city. Of the 29,000 acres zoned for commercial and industrial uses throughout LA, 70 percent saw their development capacity sliced in half, from a floor-area ratio (FAR) of 3.0 to 1.5. Since the city allows housing to be built in many of these zones, it didn’t just mean less office, retail, and manufacturing space, but fewer homes as well. The ballot initiative responsible for these changes was called Proposition U, and it’s the reason that so many commercial corridors in LA are still characterized by 1960s and ’70s-era, single-story, dilapidated strip malls. All those arterial corridors were the ones permanently frozen in time by Prop U. THE PROPOSAL To my knowledge no one has ever assessed exactly how much this instance of “planning by the ballot” actually reduced the residential capacity of Los Angeles. By my very, very rough estimate, I would put the number somewhere on the order of 1 million homes.* But whether the actual number is 1 million, 500K, or over 2 million, the conclusion is the same: If we want to keep Los Angeles affordable for residents at all income levels, we should repeal Proposition U. Repealing Proposition U would achieve several important aims. Since we’re talking about arterial, commercial corridors, the repeal would dramatically increase the supply of transit-oriented housing over the next several decades—something we desperately need at a time of record-low residential vacancy rates if we’re to have any hope of limiting continued rent increases. It would reduce development pressures on existing communities, directing development to underutilized corridors with little to no housing on them, rather than funneling developers into single-family neighborhoods […]