Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

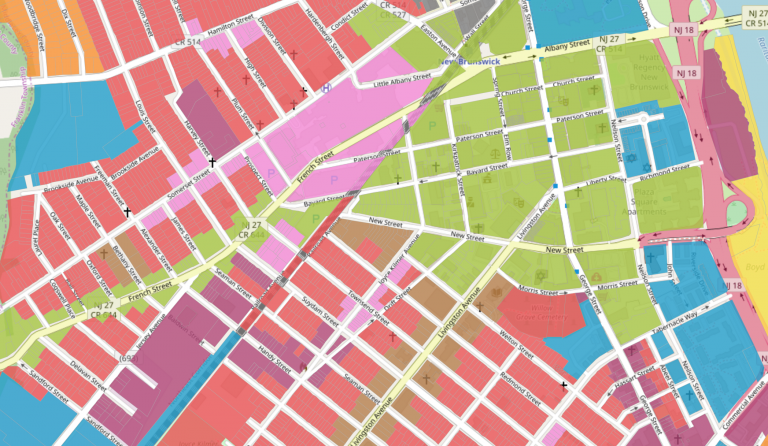

At first blush, the enterprise of interpreting the Jane Jacobs’ work might seem like one best left to the proud and peculiar few, or to put it less charitably, those of us with nothing better to do. Yet the forces of history militate against this apathy: Jane Jacobs has emerged as quite possibly the most important figure in North American urban planning in the second half of the twentieth century. Her work is now taught in every urban theory and urban planning program worth its weight in ESRI access codes. She is responsible for introducing hundreds of thousands of people to planning and urbanism (including this author) and continues to shape how many of us think about cities. In one of my more popular blog posts here on Market Urbanism—and in a forthcoming book chapter—I argue that we should interpret Jane Jacobs as a spontaneous order theorist in the tradition of Adam Smith, Michael Polanyi, and F.A. Hayek. Built into her work is a profound appreciation of the importance of local knowledge, decentralized planning, and the spontaneous orders that structure urban life. Needless to say, this is not the prevailing interpretation of the importance and meaning of Jacobs’ work. Two very different alternative interpretations prevail. In this post, I argue that both interpretations are mistaken. Jane Jacobs, Form-Based Coder Many have taken Jacobs’ particular critiques of conventional U.S. zoning, often referred to as “Euclidean zoning,” as motivating a new form of zoning that takes into account her observations on design. In contrast to the mandates of Euclidean zoning, which proscribes land-use segregation and low densities, Jacobs celebrated mixtures of land uses and urban densities. Jacobs spends large sections of Death and Life discussing in detail particular urban designs that she sees as essential to fostering urban life. Much of “Part One” focuses on […]

If you happen to visit Egypt and find yourself in the famous Tahrir Square, you might be puzzled: how could this space accommodate two million protesters? In fact, the square looked different at the time of the Arab Spring, up until the new military government ringed its central part with an iron fence. A similar transformation happened with the Pearl roundabout in the capital of Bahrain where demonstrators used to gather — it was turned into a traffic junction. In my hometown, Moscow, the square where millions called for the end of Soviet rule in 1991 now houses an hideous shopping mall. For a pro-liberty movement to raise its head, Twitter is not enough: face-to-face contact is crucial. That is why when oppressive governments want to destroy civil society, they destroy public spaces. Street markets, green squares and lively parks (think of the iconic Hyde Park corner) are places where citizens meet, negotiate and slowly learn to trust each other. Joseph Stalin knew it well, hence he made sure that city dwellers had no public spaces to socialise in. The results were devastating: chronic mistrust that post-communist societies are yet to overcome. Today, 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the levels of social capital in Dresden and Leipzig are still lower than in Munich and Hamburg, which bears its economic as well as political costs. One study shows that residents living in walkable neighbourhoods exhibit at least 80% greater levels of social capital than those living in car-dependent ones. That is something to consider, given that only a half of Brits know their neighbour’s name. The economic benefits are also clear: improved walking infrastructure can increase retail sales by 30%. London has witnessed it on Oxford Street where the creation of a Tokyo-style pedestrian crossing led to a 25% increase in turnover in the adjacent stores. In the […]

Once upon a time, New York City’s poor single people were usually not homeless because they lived in little apartments with shared bathrooms and kitchens. These units are called “single room occupancy” (SRO) units in plannerese. (When I was young, people used less flattering terms such as “fleabag” and “flophouse” to describe the nastier SRO buildings). What happened? Why are so many people sleeping on the streets of Midtown? A recent paper by NYU’s Furman Center partially answers the question, by discussing the obstacles to SRO construction. For decades, New York’s housing law has made SROs almost impossible to build, in a variety of ways: By flatly outlawing SROs, unless they are built with government or nonprofit involvement Through anti-density regulations that limit the number of dwelling units in a building; Minimum parking requirements (though these are an issue primarily in the outer boroughs). The paper recommends allowing market-rate SROs, limited density deregulation, counting SRO units as affordable housing for purposes of the city’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, exempting SROs from minimum parking requirements, and government subsidies for SROs.

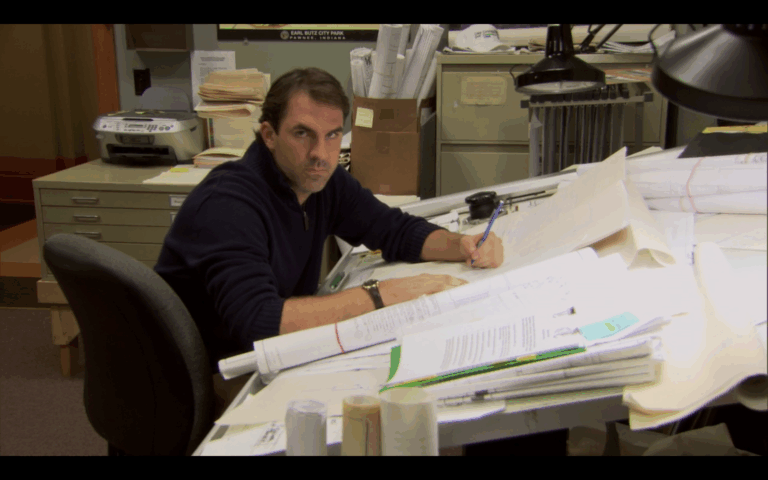

Spoiler Warning: This post contains minor spoilers about Season Two of Parks and Recreation, which aired nearly 10 years ago. Why have you still not watched it? Lately I have been rewatching Parks and Recreation, motivated in part by the shocking discovery that my girlfriend never made it past the first season. The show is perhaps the most sympathetic cultural representation of local public sector work ever produced in the United States. The show manages to balance an awareness of popular discontent with “government” in the abstract— explored through a myriad of ridiculous situations—with the more mild reality that most local government employees are well-meaning, normal, mostly harmless people who care about their communities. This makes the character of Mark Brendanawicz, Pawnee’s jaded planner, all the more interesting. It’s conspicuous that even in a show so sympathetic to local government, the city planner remains a cynical, somewhat unlikable character. Unlike Ron Swanson, Brendanawicz at one point meant well and has no ideological issues with government; he regularly suggests that he was once a true believer in his work, if only for “two months.” Yet unlike Leslie Knope, he didn’t choose government. In his efforts to win back Anne, Andy chides Brendanawicz as a “failed architect,” an insult which seems to stick. Brendanawicz ultimately leaves the show as an unredeemed loser: after taming his apparent self-absorption and promiscuity, he prepares to propose to Anne, only to have her preemptively break up with him. When the government shutdown occurs at the end of Season Two, Brendanawicz takes a buyout offer, and resolves to go into private-sector construction. Leslie, who had once adored him, dubs him “Brendanaquits,” and we never hear from Pawnee’s city planner again. It isn’t hard to see why Brendanawicz was unceremoniously scrapped: he was ultimately a call-back to the harsher world […]

In my regular discussions of U.S. zoning, I often hear a defense that goes something like this: “You may have concerns about zoning, but it sure is popular with the American people. After all, every state has approved of zoning and virtually every city in the country has implemented zoning.” One of two implications might be drawn from this defense of Euclidean zoning: First, perhaps conventional zoning critics are missing some redeeming benefit that obviates its many costs. Second, like it or not, we live in a democratic country and zoning as it exists today is evidently the will of the people and thus deserves your respect. The first possible interpretation is vague and unsatisfying. The second possible interpretation, however, is what I take to really be at the heart of this defense. After all, Americans love to make “love it or leave it” arguments when they’re in the temporary majority on a policy. But is Euclidean zoning actually popular? The evidence for any kind of mass support for zoning in the early days is surprisingly weak. Despite the revolutionary impact that zoning would have on how cities operate, many cities quietly adopted zoning through administrative means. Occasionally city councils would design and adopt zoning regimes on their own, but often they would simply authorize the local executive to establish and staff a zoning commission. Houston was among the only major U.S. city to put zoning to a public vote—a surefire way to gauge popularity, if it were there—and it was rejected in all five referendums. In the most recent referendum in 1995, low-income and minority residents voted overwhelmingly against zoning. Houston lacks zoning to this day. Meanwhile, the major proponents of early zoning programs in cities like New York and Chicago were business groups and elite philanthropists. Where votes were […]

The adoption of zoning as a means of preventing external costs led to inefficient use of land and caused many individuals to suffer great unfairness.

Subsidies to transportation tend to lengthen supply and distribution chains. Large corporations are artificially competitive against smaller, local firms.

by Samuel R Staley Before the twentieth century land-use and housing disputes were largely dealt with through courts using the common-law principle of nuisance. In essence if your neighbor put a building, factory, or house on his property in a way that created a measurable and tangible harm, courts could intervene on behalf of a complainant to force compensation or stop the action. This pro-property rights approach maximized liberty and minimized the ability of citizens and elected officials to politicize the development process. This changed with the Progressive movement. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Progressives argued that government should become more professional. Rather than being limited, government should use its resources to pursue the “public interest,” loosely defined as whatever the general public decided through democratic processes was the proper scope of government. Legislatures and, by extension, city commissions made up of elected citizens would set policy and goals while a cadre of trained professionals would use the techniques of scientific management to implement policies. One of the leading Progressives of the day, Woodrow Wilson, was skeptical of the value of elected bodies such as Congress because they interfered with scientific management of government. While many in the twenty-first century might be tempted to dismiss this public-interest view of government—indeed an entire academic subdiscipline, Public Choice, has emerged to demonstrate the foibles of governments and explore “government failure”—Progressive ideas held a lot of appeal at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition to national concerns over industries such as oil, steel, and railroads, local governments were rife with corruption, waste, and inefficiency. Reforms, such as the city-manager form of government, civil-service exams, and in some cases even municipal ownership of utilities, were thought to provide more transparency and accountability than the patronage-laden times of political bosses. (Today municipal […]

Richard Rothstein’s “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America” should be required reading for YIMBYs and urbanists of any ideological stripe. Rothstein argues that housing segregation in the US has been the intentional outcome of policy decisions made at every level of government and that the idea of segregation as phenomenon driven by spontaneous self-sorting is largely a myth. Two major themes permeate the book: (1) the ways in which government has consistently intervened in the housing and land markets and (2) how these interventions were designed to pick winners and losers. The federal policy of underwriting loans for specific kinds of development (single family detached housing) and for specific people (whites) is an example that the author explores in depth. And after reading his account, I can safely say that I have a far better understanding of how nearly a century’s worth of policy interference has distorted markets and doled out privilege and oppression in equal measure. Throughout the book, Rothstein brings in the stories of specific people and places to add depth to his account. This both keeps things interesting and serves to humanize the story in a way that many tracts on policy fail to do. When he’s describing the lives of black Americans who were forced into soul crushing commutes because they were legally prohibited from living near their jobs, or families who had their houses firebombed for daring to move into a segregated neighborhood while police stood on their front lawns and watched…you remember that policy matters because it affects real people. And that real people suffered terrible wrongs for no other reason than the accident of their birth. Again, if you care about US housing policy, you must read this book. It’s impossible to understand where we are […]

This post was originally published at mises.org and reposted under a creative commons license. It’s no secret that in coastal cities — plus some interior cities like Denver — rents and home prices are up significantly since 2009. In many areas, prices are above what they were at the peak of the last housing bubble. Year-over-year rent growth hits more than 10 percent in some places, while wages, needless to say, are hardly growing so fast. Lower-income workers and younger workers are the ones hit the hardest. As a result of high housing costs, many so-called millennials are electing to simply live with their parents, and one Los Angeles study concluded that 42 percent of so-called millennials are living with their parents. Numbers were similar among metros in the northeast United States, as well. Why Housing Costs Are So High? It’s impossible to say that any one reason is responsible for most or all of the relentless rising in home prices and rents in many areas. Certainly, a major factor behind growth in home prices is asset price inflation fueled by inflationary monetary policy. As the money supply increases, certain assets will see increased demand among those who benefit from money-supply growth. These inflationary policies reward those who already own assets (i.e., current homeowners) at the expense of first-time homebuyers and renters who are locked out of homeownership by home price inflation. Not surprisingly, we’ve seen the homeownership rate fall to 50-year lows in recent years. But there is also a much more basic reason for rising housing prices: there’s not enough supply where it’s needed most. Much of the time, high housing costs come down to a very simple equation: rising demand coupled with stagnant supply leads to higher prices. In other words, if the population (and household formation) is […]