Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

I don’t know how successful artificial intelligence will be. But let’s agree, for the moment, to consider a reasonably optimistic case where AI delivers significant productivity gains across a broad range of tasks – but not in a way that radically alters our Newtonian constraints. What would happen to housing economics and, consequently, housing politics?

Karl Marx divided the economic world into capital and labor. More recent economists have frequently (and self-regardingly) divided labor into low-skill and high-skill. In an AI world, we need to start talking about inscriptible and uninscriptible labor. I’m using a circular definition on purpose – AI will replace inscriptible labor because inscriptible labor is the type that AI is good at replacing – because I have only a fuzzy idea what AI will be good at.

(Why inscriptible rather than legible, in a James C. Scott sense? I thank Bard for the suggestion. Think about visual art – AI is probably no better than humans at guessing what nuances a human artist intended, but it can produce human-quality visual art rich with nuance. Since AI’s value is partly predicated on repetition speed, it will thrive in arenas where failures are costless. Thus, AI may be formulating 99% of new drugs in a few years even if nobody trusts it to perform a simple surgery. That’s an inscriptibility difference, not a legibility difference.

The most inscriptible human tasks are presumably those that simpler software replaced long ago, usually called “routine.” The big surprise of 2023 AI was the advances that software made with tasks we have considered creative. The “routine” concept was valuable as long as physical and informational machines advanced at comparable paces. But with informational machines far outpacing physical ones, it now seems that routine tasks handling physical materials are likely to be assigned to humans longer than non-routine tasks handling information.

Will any capital be replaced by AI? Other software and some intellectual property, sure. But most capital is buildings and vehicles.

Construction, especially low-rise residential construction, relies heavily on uninscriptible labor – individual workmen solving physical problems on a site-by-site basis.

To be sure, there have been and ought to be more productivity increases. But promising changes remain just out of reach. Factory-built housing is the Brazil of construction. And AI adds almost nothing to the relevant mid-20th century factory techniques. Besides, richer consumers (we’ll get to that) will want bespoke, not standardized, homes.

Looking upstream – softwood lumber growing and harvesting, Portland cement manufacture – one sees few obvious gains from better software.

Construction will gain a bit from the “ripple effect”: as people leave sectors where labor demand declines, more will enter construction.

But overall, construction productivity will be a laggard in an era of potentially – hopefully – high productivity growth. Any argument for a big AI effect in construction (e.g., via inventions) must admit even larger effects in most other fields. The robots will eat plumbers last.

In our hypothesized future, most workers will be more productive than they are today. (Some – I think of drivers – will experience so much productivity increase that they lose their jobs.) As consumers, most will face a world of higher wages (or, equivalently, lower prices).

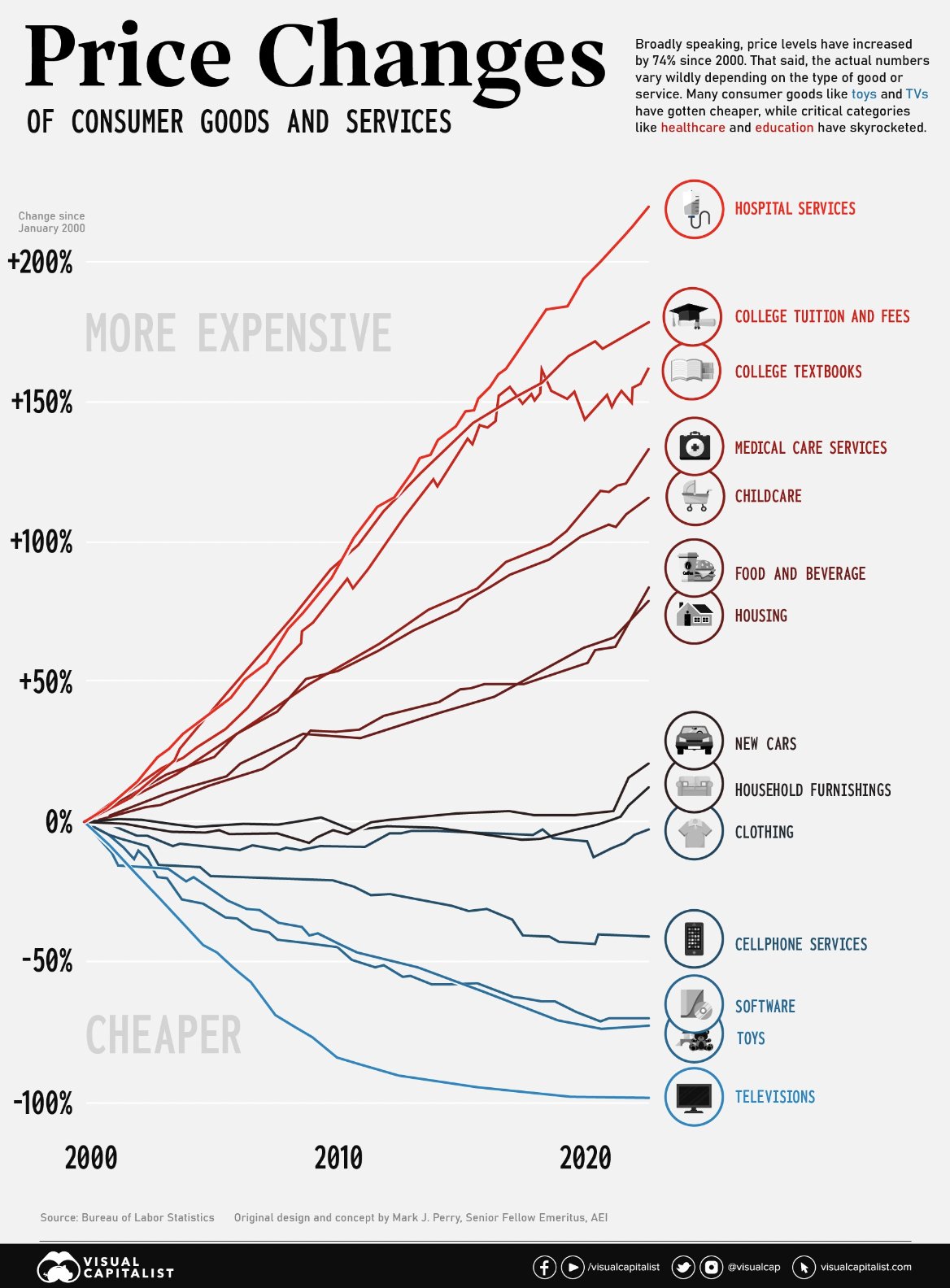

This popular graphic shows how price levels have changed in 20 years. Overall inflation came in just below the price of housing over this period; average wages grew a bit more. AI, in our optimistic scenario, takes a big bite out of the eds-and-meds inflation near the top of the graph.

That’s great – but it will leave housing even more exposed as a productivity laggard.

So what do deep-pocketed consumers do when they have more money, fewer college loans, and lower medical expenses?

Economists have spent lots of time studying what happens to housing expenditures when people have more money. There are a range of estimates, each with its own nuance. A solid starting point is that the average share of income spent on housing is mostly constant across time and place, implying an income-expenditure elasticity of 1.0 (Davis & Ortalo-Magne 2011). A more optimistic estimate of that elasticity is 2/3 (Albouy, Ehrlich, and Liu 2016). A related estimate of the income-home price elasticity finds a U.S. average of 0.81, but with wide variation between cities (Oikarinen et al 2018).

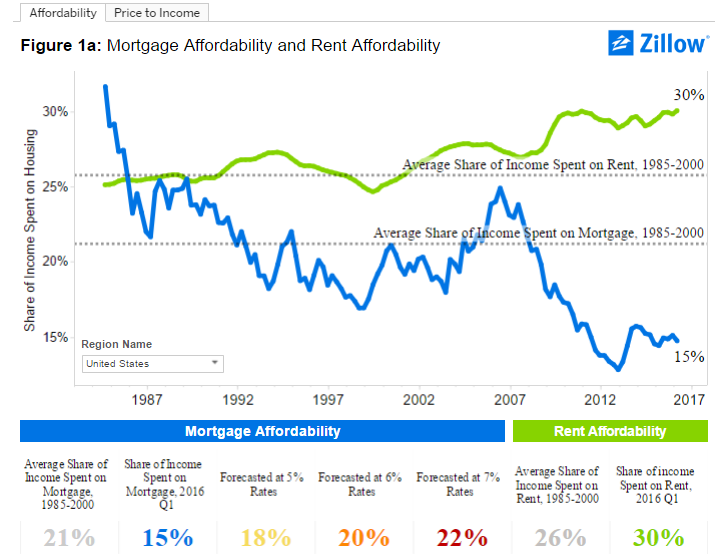

Once we split rental and ownership costs out, it’s obvious that interest rates and timing luck for purchasers can move observed “affordability” metrics drastically:

Speculating, I predict that housing expenditure as a share of income will rise around these choppy trends. There’s no deep reason why it should be constant. If other major categories are cheaper (and the categories are complements), then expenditures should rise. The services we derive from “shelter” are also growing – a nice house today includes not only a home office but what could only be described to a 1960s family as a miniature cinema.

Obviously, there are two ways to spend more on housing: Buy more or better housing, or bid up the per-quality-adjusted-square-foot price. Oikarinen et al found what market urbanists expect: the home price elasticity was smaller in cities with a less constrained housing supply.

Higher per-square-foot housing prices are obviously going to hurt whoever is on the outside of this boom. And even higher-quality housing stock has historically made housing concerns more salient. I’ve illustrated this article with pictures of old houses. They’re cute, but they are far below modern legal and cultural standards.

In their short Mercatus book on high prices and Baumol’s cost disease, Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok note that having a few high cost sectors is a price worth paying for progress:

There is nothing wrong with a future world in which consumers spend most of their income on live musical performances.

But people in 2040 or 2080 are no more likely than our own generation to be complacently grateful for their material abundance relative to the past. Our own YIMBY movement, after all, arose not from poverty but from constrained affluence. As I’ve pointed out elsewhere, the oddest thing about the “abundance agenda” moment is that it’s occurring at the most materially-abundant time in history (so far).

AI success will not extinguish the motives and causes of YIMBY v. NIMBY politics. Rather, it will deepen them. An AI-enabled world will produce even more people who fit the profile of YIMBY recruits. And, by raising the share of expenditure on housing, it will raise the stakes for both sides.

Among those left behind by productivity growth, housing will be – even more than it is now – the clearest outward signal of income inequality. The political and ethical stakes of the housing debate are going to rise, not fall.

Build accordingly.