Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Monday, Y-Combinator, an early-stage technology startup incubator, announced it will “study building new, better cities.”

Some existing cities will get bigger and there’s important work being done by smart people to improve them. We also think it’s possible to do amazing things given a blank slate. Our goal is to design the best possible city given the constraints of existing laws.

They are embarking on an undertaking of noble intentions, and I will explain why the technology sector needs to be at the forefront of thinking about cities. However, in the pursuit of designing “new” cities from a “blank slate” they have begun their quest with one fatally flawed premise, that wise technocrats can master-build entirely new cities catering to the infinitely diverse set of needs and desires of yet-to-be-identified citizens.

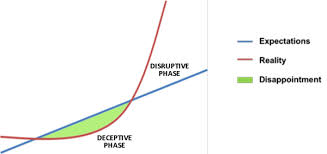

Any visions of city-building must first humbly acknowledge that cities are an “emergent” phenomena. According to wikipedia, “emergence is a process whereby larger entities, patterns, and regularities arise through interactions among smaller or simpler entities that themselves do not exhibit such properties.” What makes cities vibrant are the “spontaneous order” which emerges among city dwellers as they pursue their individual desires. Cities are like the internet – networks, patterns, and interactions emerge not through design but from spontaneous order. Like no entity could conceivably understand or control the internet, no entity has the knowledge to anticipate the desires of millions of individual agents, and design a city accordingly. This is called the “knowledge problem.”

According to economist Friedrich Hayek:

If we can agree that the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place, it would seem to follow that the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them.

We cannot expect that this problem will be solved by first communicating all this knowledge to a central board which, after integrating all knowledge, issues its orders. We must solve it by some form of decentralization. But this answers only part of our problem. We need decentralization because only thus can we insure that the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place will be promptly used.

Because of flawed philosophical underpinnings that emphasized top-down design (urban planning) and failure to acknowledge the emergent nature of cities, American cities nearly destroyed themselves in reaction to the 20th Century’s greatest technological disruption, the automobile. Cities’ master builders, armed with the best intentions progressive philosophy had to offer at the time, devastated vibrant communities and urbanity through the use of urban renewal projects, overbuilt a system of highways catering to the automobile, abandoned rail lines, and utilized zoning to separate homes from commercial activity and push growth further from where it was desired.

Perhaps future technocrats won’t make the same mistakes past technocrats made in reaction to the automobile. But to “design cities” successfully will take a strong dose of humility that was lacking during the Progressive Era. The focus should be on issues of governance, culture, and institutions instead of a top-down, build-from-scratch mindset. This may sound like it is in the wheelhouse of social science instead of technology, but in fact, we can find analogies. Show technologies can (and perhaps, must) help foster emergent systems without being compelled to dream up all of the system’s components together. This is commonly seen in the use of technology in the creation of platforms. Technology brought us platforms such as Microsoft’s Windows, internet protocol, Apple’s iTunes app store, Wikipedia, WordPress, ebay, and Uber. Likewise, technology can be utilized to create platforms of governance (or Government as a Platform as Tim O’Reilly refers to it). Platforms for governance and conflict resolution at the city scale would likely incorporate disparate, yet integrated systems of artificial intelligence, physical sensors, empathic interfaces, and machine learning to facilitate “Spontaneous Order” without implementing a top-down design.

Let us also set aside the premise that we must work “within the constraints of current law,” as effectively enforcing “current law” (particularly zoning) will be impractical and dysfunctional in the coming dynamism. Platforms of governance using technology will develop over the decades, and the need for more dynamic governance will become more pressing as developing exponential technologies disrupt the construction industry and the dynamism of cities accelerate as a result.

Exponential technologies such as 3d-printing, robotics, and artificial intelligence will inevitably disrupt the factors of production of buildings, and thus cities. This will usher in a new paradigm where construction costs, and thus rents steadily decrease instead of increase. Buildings will be constructed in days instead of years. Cities will become more affordable and dynamic than ever, and perhaps new cities will emerge seemingly overnight as the speed and economics of construction accelerates.

This new paradigm will more likely be led by firms that more closely resemble technology companies than the current regime of developers, realtors, construction companies, and city planners. For this reason, the technology sector must be at the center of the conversation of what makes cities great, and how cities can best meet the needs of its inhabitants.

A society where housing and the components of vibrant cities are abundant and affordable is a vision worth striving towards. As is a society where disputes are resolved speedily in a bottom-up fashion. In many ways, the technology sector is already on a path to make that happen – they just may not yet realize it. Now is the time the technology sector and intellectuals must look at the new urban paradigms technologies will usher in, and start thinking of how to responsibly handle the humongous opportunity. For that reason, I applaud Y-Combinator. Aside from Y-Combinator’s flawed premise, I believe technology will usher in a new paradigm of abundance and cooperation in cities, and now is the time for the conversation to begin in earnest. We at Market Urbanism are eager to be a part of that conversation.

[…] Hengels of Market Urbanism recently published a critique of city planning. Hengels […]

These men of system need to stick to making things that we might want to buy rather than forcing upon us their vision of how we need to live.

However, I’m still bitter that Walt Disney did not live long enough to build EPCOT!

Irvine, Reston, Columbia, and The Woodlands, anyone?

It doesn’t sound to me like the Y Combinator people are committed to master-planning everything. Maybe that’s the direction they’ll go, but I think there’s an open path to something more like a “framework” than a “master plan.” That is, setting up a city that is open to change and experimentation—primarily motivated by it, even. I have my own ideas for a whole host of top-down plans that would make for great cities, but the openness to change is really the heart of the matter. If this group can facilitate that, they might just be successful.

[…] Market Urbanism, Hengels points out how reliance on a previous ‘new’ technology, the car, led cities […]

[…] Market Urbanism, Hengels points out how reliance on a previous ‘new’ technology, the car, led cities […]

Actually I’d say the opposite, the conversation is dominated by tech speak. It should be led by social innovators and senior policy makers, with clear social benefits described, then mapped to tech capabilities. Otherwise we end up with an endless parade of gadgetry that does little to delivery real impact to citizens, in terms they value.

I’m much less sure than you are that they *don’t* understand that cities are products of the “emergence” of “spontaneous order”. I’d guess they’re interested in better *rules* – a “framework” as Shane describes.