Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Want to live in San Francisco? No problem, that’ll be $3,000 (a month)–but only if you act fast.

In the last two years, the the cost of housing in San Francisco has increased 47% and shows no signs of stopping. Longtime residents find themselves priced out of town, the most vulnerable of whom end up as far away as Stockton.

Some blame techie transplants. After all, every new arrival drives up the rent that much more. And many tech workers command wages that are well above the non-tech average. But labelling the problem a zero sum class struggle is both inaccurate and unproductive. The real problem is an emasculated housing market unable to absorb the new arrivals without shedding older residents. The only solution is to take supply off its leash and finally let it chase after demand.

Strangling Supply

From 2010 to 2013, San Francisco’s population increased by 32,000 residents. For the same period of time, the city’s housing stock increased by roughly 4,500 units. Why isn’t growth in housing keeping pace with growth in population? It’s not allowed to.

San Francisco uses what’s known as discretionary permitting. Even if a project meets all the relevant land use regulations, the Permitting Department can mandate modifications “in the public interest”. There’s also a six month review process during which neighbors can contest the permit based on an entitlement or environmental concern. Neighbors can also file a CEQA lawsuit in state court or even put a project on the ballot for an up or down vote. This process is heavily weighted against new construction. It limits how quickly the housing stock can grow. And as a result, when demand skyrockets so do prices.

To remedy this, San Francisco should move from discretionary to as-of-right permitting. In an as-of-right system, it’s much more difficult to stop construction. As long as a project meets existing land use requirements, city planners have to issue a permit. And although neighbors can sue based on nuisance, they don’t have any input in the actual permitting process. As-of-right permitting would go a long way toward defanging NIMBYs and overzealous planners.

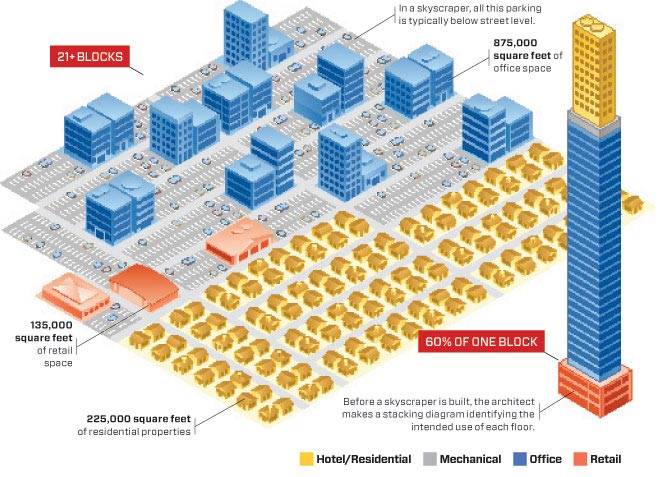

But even if San Francisco opened up the permitting floodgates, height limits, floor-to-area ratios, zoning designations, and minimum parcel sizes all prevent land from being put to its best use. Land use restrictions like these can increase the price of housing by as much as 140% over construction costs. Relaxing–if not abolishing–these types of restrictions would be hugely beneficial.

But for as much as regulatory reform would help, there’s another way of encouraging supply to catch up with demand. And, interestingly enough, it involves raising taxes.

Tax the Land

The more you tax something, the less of that something society produces. Raise taxes on income and you discourage labor. Raise taxes on capital and you discourage investment. Raise taxes on property and the same logic applies; the higher the tax rates the greater the burden on new construction. But property taxes aren’t just a tax on buildings, they’re a tax on the land underneath as well. Separate the two in favor of taxing land alone, and construction is not only unburdened, it’s encouraged.

A pure land tax would amount to fixed overhead for each assessment period. This would encourage landlords to use their holdings as intensely as the market would bear. Holding a valuable parcel vacant or underused would become prohibitively expensive.

There are a few different proposals for implementing land taxation. The most aggressive approach calls for a 100% fee on land values and the abolition of all other taxes. A slightly more moderate proposal favors an 80% land tax to allow for some margin of error in assessment. The most realistic plan would be to retire San Francisco’s property tax in favor of a land tax and make the change revenue neutral. Considering the city’s property tax rate is barely over 1%, a revenue neutral land tax probably wouldn’t deliver the sun, the stars, and the moon like it would at much higher levels. That said, it would still be an improvement over the existing property tax.

Fix the Market, Not the Price

Neither rent control nor inclusionary zoning will fix the housing crisis. Both amount to price controls. Both drive up the price of market rate construction. Both create a gap between subsidized and unsubsidized housing. And as long as San Francisco can’t set its own immigration policy, there will never be enough subsidized housing to go around. It’s simply not a scalable solution. But that doesn’t mean there’s no room for a safety net.

Housing vouchers are like food stamps for….well, housing. They put resources directly in the hands of those who need them while avoiding the negative side effects of price fixing. It’s welfare that doesn’t try to mandate a price, but instead ensure that the least well off can pay whatever that price might be.

Funding via a land tax would tie the amount of revenue available for vouchers to the state of the housing market. When housing costs increase, it’s not the buildings themselves that are becoming more expensive, it’s the land that they’re sitting on. Houses aren’t wine, they don’t typically improve with age. The actual ground they sit on, however, can become more valuable if more people want to move into a neighborhood. If a sudden surge in demand sends land prices through the roof, a land tax would ensure that funding for vouchers would increase as well.

Funding through a land tax would also prevent vouchers from becoming a subsidy for landowners. Pumping other sources of revenue into housing might simply make the market more competitive and allow landlords to charge higher rents. A land tax would limit this by moving resources from landlords on one end of the market to tenants on the other end without increasing the total amount of dollars chasing housing. Regulatory reform would also limit any price increases from a voucher system since an increase in demand would better stimulate an increase in supply. The extra supply would then put downward pressure on prices.

Slowing down–let alone turning back–the rising cost of housing will require a massive amount of new construction. Relaxing land use rules will clear the path. Changing the tax code will hurry things along. And rethinking the social safety net will ensure that no one gets left behind.

Prop 13 encoded the 1% property tax rate, assessment methodology, 2% annual increases, and revaluation-at-resale into the California constitution. (Ironically, Henry George came up with his Single Tax idea while he was living in San Francisco.)

The people who voted in favor of Prop 13 should be ashamed.

Prop 13 slows down gentrification by stabilizing property taxes for current owners in rising markets. It eliminates fast, steep tax rate increases which can force out homeowners in gentrifying areas.

There are problems with Prop 13, but it is not purely bad, and intelligent people of good faith are among those who voted for it.

And why is gentrification a bad thing, why slow down the process that allow neighborhoods to get nicer? The people who own there can cash out.

Your “nicer” is probably a lot different than my “nicer”. Everything is not always about money. People live in places that they love. They become attached to their neighbors, to the business people they’ve known for decades. This is an important element of human and community health that is overlooked in all this intellectual discourse.

You want to slow it down because you don’t know everything and when you discard a group of people because you want to take what they have, you might be destroying more than you know.

Neighborhoods are about people, not just about nice houses and trendy shops.

Money always wins, though. The wealthier folks will get their “nicer” neighborhoods, regardless of what is lost. They can only see things in their own terms.

Hey Lightfoot, thanks for commenting. You are correct in that the only thing that grants someone the right to live in any particular place–this is a descriptive statement, not a normative one–is one’s ability/willingness to pay either rent or property tax. Piecemeal interventions like prop 13 are halfway measures that tend to privilege a few and make things worse for everyone else.

If we wanted to be serious about honoring incumbency, a community needs to become something concrete and defensible, not just an ephemeral agglomeration of people, places and things that someone prefers.

http://www.marketurbanism.com/2015/01/29/the-right-to-the-city/

Thanks, Jeff. I’m new to this site, and I’m happy to have found a place with such a high level of discourse.

I’m deeply involved in real estate from a lot of angles–owner, investor, agent, householder, has-been flipper–and I find the complexity of these issues, at the neighborhood level, to be daunting. I wish I had an inkling of how we can facilitate renewal (not necessarily growth) through development while respecting a reasonable degree of continuity for “incumbents”. I appreciate what I am reading here, and I’m hopeful that I’ll learn something that will help me deal with the changes in my ‘hood.

@ Lightfoot

Those are all good points, but no one has the right to live in areas impervious to change (as no one has ever had the privilege of growing old in the identical place where they grew up). Everyone has to adapt (and sometimes move) with the times.

The current situation in SF is untenable. How fair is it that two neighbors may pay much different tax rates depending on when they moved into their house? Furthermore. it is simply unfair that two tenants in the same building may be paying many times the rent than the other person.

The system is rigged against newcomers, both renters and homeowners.

Also “Gentrification” as typically understand in SF is not the only outcome. You can have redevelopment as well with far richer communities that are vertical mixed use and new zoning to eliminate cars and promote other transit options. This DO EXIST in other parts of the world but US exceptionalism likes to deny they are transferable – this is bullshit of course, just as exceptionalism always is.

No market was ever improved with decreased price transparency and higher transaction costs. No tax was ever improved by narrowing the base. And no housing market was ever improved through rent control, which Prop 13 is a form of. I’m generally a left-wing guy, but you do realize this is “Market Urbanism”?

I know, it says “Market Urbanism”, but I was taken in by the well-reasoned and thoughtful writing and comments. 😉

I mostly agree with you, but I would add that Prop 13 and rent controls are reactions to perceived unfairness, and that they do have some benefits. I bet a strong argument could be made that communities benefit greatly by using smart regulation to maintain a wide socio-economic range. Even at this site there seems to be an acknowledgement that taxation and regulation play a useful part in guiding change. It’s obvious, from recent experience, that unregulated markets

have the potential to cause a great deal of trouble.

On one hand, my retired mother has benefited but she’s also old and won’t be here in 10-20 years and her children are all happy to have her move in with them (all have kids off at college so it’s not an imposition or space problem). Change is always pain but change happens whether you wish it away or not. Right not the Bay Area housing problems are being abandoned to solutions based on nothing more than wishes and wishful thinking. That doesn’t actually work in real life so it going to be far worse soon enough.

There may be some wiggle room in the definition of “property”. Hence the separation of land vs. building may allow a wedge. Also if things get bad enough, people could vote away Prop 13 just as they voted it in. I’m actually expecting that to happen – the housing problem already is having an effect on the tech and other businesses.

[…] Read Startup article here: http://www.marketurbanism.com/2015/01/26/how-to-fix-san-franciscos-housing-market […]

I think its important to note that taxing land to encourage development does not necessarily result in higher density in the long run. Taxing land simply to encourage development in lieu of speculation can have a harmful long-term effect. http://www.marketurbanism.com/2009/01/22/taxing-land-speculation/

I’d favor land-value-tax under certain conditions:

– the bureaucracy of the city is set up in way that a feedback loop between zoning and taxes where a political entity is incentivized to loosen zoning in order to increase tax revenue.

– I would suggest that most or all revenues generated in a land-value tax be spent locally, with the hopes of turning NIMBYs into YIMBYs who want to increase land values in the area, not just values of their own home.

– the tax replaces another tax, and doesn’t just become another revenue source added to the other burdens

I completely agree with all three of those stipulations. The LVT is no silver bullet and I think that land use deregulation has to come first for either an LVT or a voucher system to do any good.

LVT does not necessarily result in higher population density, but it always results in highest and best use of land. In San Fran the highest and best use is not to have parking lot and community gardens and one or two story homes on multi-million/acre land. LVT changes this. Of course people can then CHOOSE to keep it a single family residence or parking lot, but they will pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in tax for that privilege.

Here’s a link to the Cato original of the Glaeser/Gyourko paper on housing costs: http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2002/10/v25n3-7.pdf

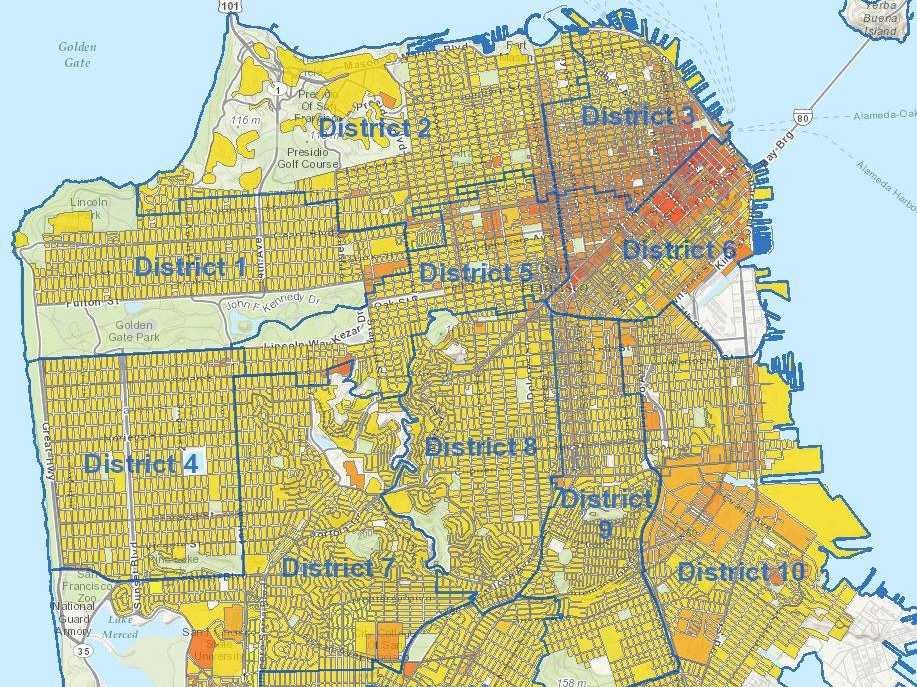

You misattributed the map I made: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=7542775

Mike, I am so sorry, my mistake! I’ll update that credit right away. Awesome tool by the way. I know a lot of folks that are going to have a lot of fun playing around with that 🙂

Thanks, and enjoy the tool — it is indeed fun, sophisticated, and useful.

[…] of this should be taken as more of a thought experiment than a policy proposal. For one, policy reform would go a long way in solving the problem of displacement without having to favor incumbency. […]

[…] of this should be taken as more of a thought experiment than a policy proposal. For one, policy reform would go a long way in solving the problem of displacement without having to favor incumbency. […]

[…] educational monopolies that guard the gates to opportunity. We manufacture the homeless by zoning for parking and pretty views over people. We manufacture addicts by marketing alcohol and drugs as […]

[…] overlays, rent control laws that benefit select households while raising prices overall, and environmental laws that slow the construction approval process. Additional zoning laws throughout Silicon […]

[…] overlays, rent control laws that benefit select households while raising prices overall, and environmental laws that slow the construction approval process. Additional zoning laws throughout Silicon Valley […]

Last month we found that our housing affordability crisis was

caused by our Planning Code which makes it very difficult to increase the

supply of housing. We may have come to a time when the majority of San

Franciscans will want to change the Planning Code and solve the affordability

crisis so that median income people will again able to live and raise families

in San Francisco.

I suggest that when a majority of voters understands the nature

of the crisis that our Board of Supervisors, or at least six of them will take

a first step and declare that there is a Crisis. The second step, which has

actually started, is to pursue the use of all City owned surplus sites for new affordable

housing. This would include: all of the MTA

owned parking lots; the BART parking lot near the Glen Park Station, the air

space above BART and the West Portal Metro stations, and others spaces; but never for our open

space parks because as we have more people we will need as much park space as

possible. Private parking lots, such as Stonestown

and the lot behind Davies Symphony Hall are also good sites for high rise

buildings. Most these sites would require some structural steel or reinforced

concrete to support the buildings above but that is much cheaper than buying

land. We should also encourage East Bay communities to build dense housing over

their BART and other parking lots.

There are two kinds of affordable, earthquake proven, construction

systems being used today in San Francisco. Either can be used at the above

sites. One is: four or five stories of wooden construction over a reinforced

concrete podium. The podium is used for commercial space and parking. The other system is the thirteen story

reinforced concrete structure which was used in the older Park Merced buildings

and which will be used again for an expanded Park Merced, starting construction

soon. I prefer the Park Merced system because this will accommodate many more

new housing units while destroying fewer existing houses and the taller

buildings will provide ample space for market rate units to help subsidize the

affordable units below.

Building on the above publicly owned sites can be started

quickly, because the land is essentially free. Developers can be selected based

on the number of affordable units that will be provided without additional

subsidy. Spot zoned can be used to allow for more dense housing if certain

conditions are met. On these sites a mix of market rate and affordable housing

units will help subsidize the affordable units and the total number of

additional units provided will increase the supply and could slow down future

increases in housing prices.

The third step is implementing a City policy that says that we will

build 40,000 or more housing units in

the approximately twenty square miles of the low density portion of our City.

These units should be in addition to the 30,000 units currently being planned

for in the more dense parts of the City.

Spot zoning can be used again for more dense housing as a conditional

use. To visualize this additional housing consider that the units will be in apartment

houses similar to those now in Park Merced, that is, thirteen stories tall with about 100 units

per building. This means that there will be: about 400 new tall buildings: or twenty

tall building per square mile and each building will on average be about 1,200 feet from the

nearest other tall building. However, it will be better to concentrate up to

four tall buildings at the intersections near BART stations and major Muni

transfer points and allow buildings to be as close as 500 feet apart close to

transit and on commercial streets. This

means that, every day the people in these neighborhoods will see one or more of

these buildings, along with few more people on the sidewalk as they walk to

their Muni stop or shopping. Those neighbors who drive a ways will see more

buildings and more traffic unless the amount of parking in the new buildings is

severely restricted. I suggest that these point increases in density surrounded

by existing low density housing will preserve most of San Francisco as it is

now while still increasing the supply of housing enough to make housing more

affordable.

Because the objective is not only about increasing density but

also improving affordability we should mandate that a high percentage of units

be affordable. We can also reduce the cost of the new units by not mandating a

minimum parking supply and actually set a low maximum supply of parking so that

people will be encouraged to reduce their cost of living by not owning a car.

The reduced parking will be acceptable to the existing neighbors if the people

in the new buildings are excluded from ever obtaining a residential parking

permit. The ground floor of the buildings on commercial streets should be mandated

to be mostly commercial to maintain and enhance our commercial streets. The

reasonable spaces between buildings will prevent the construction of a

continuous wall and shading. Even though

density is necessary some open space should remain at ground level to partially

maintain the continuity of our back yard open space areas and most of the current

front yard setbacks, with street trees will be necessary to preserve a

reasonable amount of neighborhood ambiance.

Acquiring the number of lots required for a tall 100 unit building will not be too difficult because sites always come up for sale and a

developer should be able convince adjacent owners to exchange their lots for

one or two units near the top of the building. Mandating a high percentage of affordable

housing in the new housing combined with spot zoning after sites are acquired,

rather than broad up zoning, will tend to keep the price of the sites reasonable.

Making a payment to the adjacent property owners could be a partial solution to

the political problem.

Instead of building on land how about build on the water. Floating Apartment buildings built upon concrete barges? The buildings could be built in factories, which would limit normal street construction, they wouldn’t be effected by earthquakes, they could use the bay water for cooling and use the same water for sewage (taken not dumped). When the buildings reach their end of life they can be towed back to the same factory and either refurbished or recycled.

They wouldn’t effect local architecture because they would be built on the water and would reflect a new era of San Francisco culture built on the periphery of San Francisco itself.

If you are worried by Global Warming, well they float. 😉

I heard usually engineers and tecnical workers moving to SF because of extensive job prospects. But most people moving to another city to live.

There is an article about housing in SF and Bay Area:

http://thinkandsay.net/hello-world/

Good article. I want to address a couple of mistakes commenters are making:

1. “LVT is a burden.” No, it’s the collection of the land title’s rental value. Of course, LVT would be unnecessary if we had never made the mistake of allowing land titles to be freeheld in the first place; and LV”T” wouldn’t have to exist if we were smart enough to operate a leasehold land tenure system with land titles bid on and held at market rental value from a public entity. But we’ve dug a disastrous hole — freehold land ownership — and getting to an actual free market in land will require a transition. This transition period of LVT — charging the title’s rental value from title owners who already paid capitalized rent in the form of an up-front price — is the perceived “burden” of LVT. If people wanted to effect a politically amicable change to a free land market, this “burden” could be mitigated or altogether avoided through various concessions, although it would amount to society buying its way out of slavery.

2. “LVT isn’t a silver bullet.” LVT is one way to publicly collect land rent. Public land rent collection, in place of taxation, pretty much is the silver bullet. It would end sprawl as we know it, render eminent domain obsolete and zoning changes uncontroversial (no huge unearned windfalls or losses to title holders); it would end poverty and disincentivize exclusionary violence; it would add back the trillions of dollars of economic activity destroyed by the deadweight loss of production taxes … I could go on … Most of the positive effects would result even with stupid and restrictive land use regulations, which I agree should be abolished.

3. “Prop 13 is not all bad.” It entrenches freehold land ownership (a monopoly on life) into the California Constitution. It therefore guarantees a perpetual struggle to exist for anyone who doesn’t freehold valuable land, including the public body of California itself. It is as bad as any piece of legislation can possibly be without outright being titled “Proposition for the Destruction of Civilization.”

I applaud this article for talking about land tenure. It is impossible to have “market urbanism” or anything market-related at all without first having a free market in land titles — that is, titles that are leaseheld from the commons. Thanks.

@jefffong:disqus, you linked to this article https://www.jacobinmag.com/… referring to it as “inaccurate and unproductive”. Just curious, why do you say this?