Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

I recently saw a tweet complaining that left-wing YIMBYs favored urban containment- a strategy of limiting suburban sprawl by prohibiting new housing at the outer edge of a metropolitan area. (Portland’s urban growth boundaries, I think, are the most widely…

"These two homes straddle a 2010 zoning boundary change. The result: The house in duplex zoning converted into two homes, and the other converted into a McMansion that cost 80% more." - Arthur Gailes

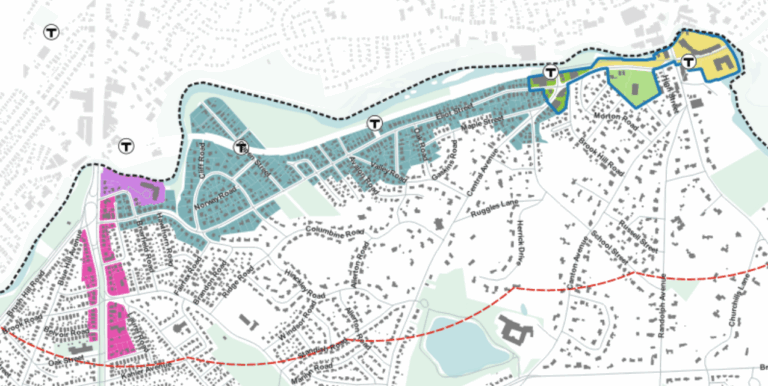

“Wow!” the reporter said, “I knew you from Milton, but I didn’t know you were from East Milton. Tell me what it feels like?” Well, until last week it was not that dramatic. East Milton is an old railroad-commuter neighborhood favored by affluent Boston Irish. It’s separated from the City of Boston by the Neponset River estuary and from the rest of Milton by a sunken interstate highway that makes it more congested and big-city than the rest of town. MBTA Communities In January 2021, Massachusetts passed the first transit-oriented upzoning law of the YIMBY era, now called “MBTA Communities,” “MTBA-C”, or “Section 3A”. Implementing regulations assigned a multifamily zoning capacity to each town. Milton was always going to be one of the toughest cases for MBTA Communities. The northern edge of town is served by the Mattapan Trolley, which John Adams rode to the Boston Tea Party links up to the Red Line at Ashmont. The trolley makes Milton a “rapid transit community”, which means it has to zone for multifamily units equal to 25% of its housing stock. Among the dozen towns in the rapid transit category, Milton is the only one where less than a quarter of current housing units are multifamily; it also has few commercial areas to upzone. East Milton dissents East Milton voters went to the polls on Wednesday and led a referendum rebuke of the plan. In Ward 7, it wasn’t close: 82% opposed the rezoning. The Boston Globe offered a helpful breakdown of the surprisingly varied voting: There are several hypotheses as to why the neighborhood went against rezoning so hard, all probably played a role. East Milton was assigned more than half the net new multifamily zoning capacity despite lacking good transit access. The neighborhood has been in a contentious, multiyear […]

Arbitrary Lines is the newest must read book on zoning by land use scholar and Market Urbanism contributor, Nolan Gray. The book is split into three sections, starting with what zoning is and where it comes from followed by chapters on its varied negative effects, and ending with recommendations for reform. For even deep in the weeds YIMBYs, it’s well worth picking up. There’s nothing dramatically controversial here, but give it a thorough read and you’re guaranteed to learn something new. In particular, the book’s third section on reforms is outstanding. It starts with a slate of policy proposals typical to this kind of text, but quickly goes much farther afield. After suggested policy changes, we’re invited to consider a world without zoning via an in-depth look at Houston’s land use regime. Here we’re treated to both an explanation of how it works and the unique political history that left the city unsaddled with zoning. Nolan goes on to close his recommendations with a call to reimagine what a city planner could be in a post-zoning American city; a call that, as a former New York City planner, he is uniquely fit to make. Aside from the content, this book deserves points for prose. Arbitrary Lines is blessedly readable. The writing flows and the varied anecdotes interspersed throughout the book make it feel less like a policy tract and more like a conversation with your favorite professor during office hours. For those already initiated, buy the book and enjoy nodding your head and learning a couple new things. And for those trying to share the good news of land use reform, consider making Arbitrary Lines that one thing you get friends or family to read. It’s among the most accessible books on land use I’ve ever read, and it’s a […]

There was an interesting article in the New York Times magazine this week on the rise of extended stay hotels, which specialize in renting to a group within the working poor- people who have the cash for weekly rent, but cannot easily rent traditional apartments due to their poor credit ratings. This seems like a public necessity – but even here the long arm of big government seeks to smash affordability. The article notes that Columbus, Ohio “passed an ordinance that subjects them to many of the same regulations as apartments” because “The hotels had an unfair competitive advantage.” In other words, the city is basically rewarding landlords for turning out bad-credit tenants, and punishing the hotels who seek to house them.

Someone just posted a video on Youtube using Houston, Texas as an argument in favor of zoning. The logic of the video is: Houston is horrible; Houston has no zoning; therefore every city should have conventional zoning. This video and its logic are impressively wrong, for several reasons. First, I’ve been to Houston and most of what I saw looks nothing like the video – there are plenty of blocks dominated by houses and the occasional condo. Second, most of the photos in the video could have easily happened in a zoned city, because one block in a neighborhood could be residential and the next block could be commercial, so the commercial or industrial activities can be easily viewable from the residential areas (not that anything is wrong with that). Third, most other automobile-dependent cities aren’t any prettier than Houston; a strip mall in Houston doesn’t look any worse than a strip mall in Atlanta. Fourth, it completely overlooks the negative side effects of zoning as it is practiced in most of the United States (many of which have been addressed more than once on this site). Typically, residential zones are so enormous that most of their residents cannot walk to a store or office. Moreover, density limits everywhere limit the supply of modest housing, thus creating housing shortages and homelessness. Finally, Houston’s negative characteristics are partially a result of government spending and regulation; as I have written elsewhere, that city has historically had a wide variety of anti-walkability policies, so it is far more regulated than the video suggests.

For over a century, policymakers have argued that homeowners take better care of their neighborhood and are just generally more desirable in other ways. As early as 1917, the federal Labor Department created a propaganda campaign to encourage home ownership. And in 1925, Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover wrote “Maintaining a high percentage of individual home owners is one of the searching tests that now challenge the people of the United States…The present large proportion of families that own their own homes is both the foundation of a sound economic and social system and a guarantee that our society will continue to develop rationally as changing conditions demand.” In many ways, Hoover was successful. In 1920, about 45 percent of households lived in owner-occupied housing; today, about 64 percent do. Mass homeownership might have had no negative side effects in a society in which most people live in the same house until they are dead, and as a result are not overly concerned with the house’s resale value. But in modern America, people often hop from one house to the other, selling houses when they move, retire, or just add another child or two to their families. And when people expect to sell their homes in a few years, they naturally want those homes to get more expensive (or to use a common euphemism, to “appreciate in value” so homeowners can “accumulate wealth”). To help achieve this goal, homeowners have a strong incentive to lobby government to use zoning codes and other regulations to limit housing supply, in order to help homes get more expensive (or in zoning-talk, “increase property values”). And because government has been quite successful in doing exactly that, housing costs have exploded in many metro areas, which in turn means that more and more people cannot afford […]

This book, available from solimarbooks.com, is a set of very short essays (averaging about three to five pages) on topics related to urban planning. Like me, Stephens generally values walkable cities and favors more new housing in cities. So naturally I am predisposed to like this book. But there are other urbanist and market books on the market. What makes this one unique? First, it focuses on Southern California, rather than taking a nationwide or worldwide perspective (though Stephens does have a few essays about other cities). Second, the book’s short-essay format means that one does not have to read a huge amount of text to understand his arguments. Because the book is a group of short essays, it doesn’t have one long argument. However, a few of the more interesting essays address: The negative side effects of liquor license regulation. Stephens writes that the Los Angeles zoning process gives homeowners effective veto power over new bars. As a result, the neighborhood near UCLA has no bars, which in turn causes UCLA students go to other neighborhoods to drink, elevating the risk to the public from drunk driving. The Brooklyn Dodgers’ move to Los Angeles; Los Angeles facilitated the transfer by giving land to the Dodgers- but only after a referendum passed with support from African-American and Latino neighborhoods. On the other hand, the construction of Dodger Stadium displaced a Latino community. To me, this story illustrates that arguments about “equity” can be simplistic. Los Angeles Latinos were both more likely than suburban whites to support Dodger Stadium, yet were more likely to be displaced by that stadium. So was having a stadium more equitable or less equitable than having no stadium? (On the other hand, a stadium that displaced no one might have been more equitable than either outcome). […]

Some commentators are slightly agog over an academic paper by Andres Rodrieguz-Pose and Michael Storper; Richard Florida writes that they shows that ” the effect of [housing] supply has been blown far out of proportion. ” Most of this paper isn’t really about the effect of housing supply on prices at all. Instead, the first 80 percent of the paper seems to argue that it makes no sense for low-skilled domestic workers to live in cities, because “Several decades ago mid-skilled work was clustered in big cities, while low-skilled work was most prevalent in the countryside. No longer; the mid-skilled jobs that remain are more likely to be found in rural areas than in urban ones.” (p. 20). The authors’ attack on upzoning is in the last few pages, and is based on broad, sweeping generalizations rather than actual data. First, they say that upzoning “would very likely involve replacing older and lower-quality housing stock in areas highly favoured by the market, effectively decreasing housing supply for lower income households in desirable areas.” (p. 30). They cite no source or data for this assertion- just pure conjecture. What’s wrong with their claim? First, such gentrification happens without upzoning; for example, in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, gentrification occurred through renovation of existing structures, rather than new, taller buildings- and of course places where new construction is politically difficult (such as San Francisco and Manhattan) are notorious for gentrification. Second, it assumes that new housing inevitably replaces older housing, rather than, say, vacant lots- an obvious overgeneralization.. Second, they rely on the “but we’re already building new housing!” argument. They cite a paywalled newpaper article to support this statement: “rents are now declining for the highest earners while continuing to increase for the poorest in San Francisco, Atlanta, Nashville, Chicago, Philadelphia, Denver, Pittsburgh, […]

Zoning regulations inflict great harm. But it is difficult for Americans to imagine the cost of zoning in Indian cities. Delhi is one of the most crowded cities in the world, and there is great demand for floor space. But real estate developers are not allowed to build tall buildings.