Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

I frequently reference my post summarizing the interesting research at last year’s Urban Economics Association conference. This year was as insight rich as ever. And the Montreal setting was truly special – it’s a city that’s as European as any…

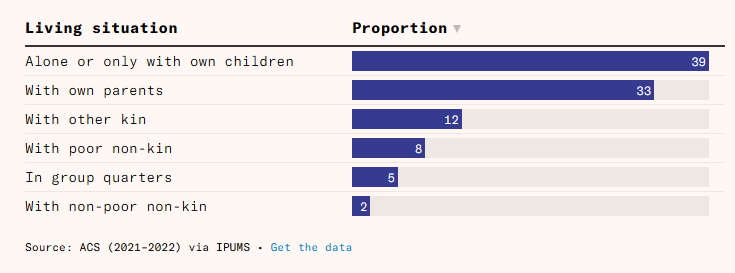

We can all understand the distinction between individual and systemic causes of homelessness. Can we apply the same rigor to potential solutions?

Delete all Seattle's highways. Invent new neighborhoods. Explain macroeconomic trends with home size. Money flows uphill to water. Do NIMBYs really hate density? Urban economics is on a tear.

A new paper proposes that increasing diversity explains 90% of the recent decline in birthrates. Lyman Stone says it's nonsense.

The traditional model of cities proves useful yet again - even when researchers neglect their discipline's roots.

Research shows that the implementation of an eviction moratorium significantly disadvantaged African Americans in the housing search process.

A friend asked what are the best papers supporting land use liberalization. That’s a broad question, but here are some of my answers. Affordability The basic case for zoning reform, across the political spectrum, is that the rent is too damn high. Michael Manville, Michael Lens, and Paavo Monkkonen give a combative and accessible review of the evidence in their Urban Studies paper (2020). The principal drawback is that it is rapidly becoming dated, as evidence and research come in from more recent reforms. The most important of those may be Auckland’s, which Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy has reported in a few papers, including this Economic Policy Center working paper (2023). Using a synthetic control method (which is not perfect, to be sure), Greenaway-McGrevy finds that upzoned areas had 21 to 33 percentage points less rent growth. A new candidate for the best review of the evidence on zoning reform and affordability is Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine M. O’Regan’s late 2023 working paper, “Supply Skepticism Revisited.” Racial integration Many authors from different disciplines have shown that both the intent and effect of zoning as practiced in the U.S. were racist and classist. That is, zoning policies have separated people by race, homeownership status, and income more than would have occurred in an unregulated market. Allison Shertzer, Tate Twinam, and Randall Walsh’s review of the evidence in Regional Science and Urban Economics (2022) is concise and helpful. However, fewer authors have attempted to show that removing specific zoning restrictions reduces existing patterns of segregation. One is Edward Goetz, in Urban Affairs Review (2021). He makes a qualitative argument. I’m unaware of a good causal, quantitative paper showing how broad upzoning impacts local integration (but I would happily commission it if anyone wants to write it!) Environment & climate Along some […]

Updated 1/11/24 to add 3 new papers, Wegmann, Baqai, and Conrad (2023), Dobbels & Tavakalov (2023), and Hamilton (2024). The original post was published 3/14/23. A concerted research effort has brought minimum lot sizes into focus as a key element in city zoning reform. Boise is looking at significant reforms. Auburn, Maine, and Helena, Montana, did away with minimums in some zones. And even state legislatures are putting a toe in the water: Bills enabling smaller lots have been introduced [in 2023] in Arizona, Massachusetts, Montana, New York, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. The bipartisan appeal of minimum lot size reform is reflected in Washington HB 1245, a lot-split bill carried by Rep. Andy Barkis (R-Chehalis). It passed the Democratic-dominated House of Representatives by a vote of 94-2 and has moved on to the Senate. City officials and legislators are, reasonably, going to have questions about the likely effects of minimum lot size reductions. Fortunately, one major American city has offered a laboratory for the political, economic, and planning questions that have to be answered to unlock the promise of minimum lot size reforms. Problem, we have a Houston Houston’s reduced minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet in 1998 (for the city’s central area) and 2013 (for outer areas). This reform is one of the most notable of our times – and thus has been studied in depth. For a summary treatment, see Emily Hamilton’s 2023 case study. To bring all the existing scholarship into one place, I’ve compiled this annotated bibliography covering the academic papers and some less-formal but informative articles that have studied Houston’s lot size reform. Please inform me of anything I’m missing – I’ll add it. Political economy of Houston’s reform M. Nolan Gray & Adam Millsap (2020). Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis […]

Update 11/20: Chang-Tai Hsieh counters that Greaney’s critique ignores general equilibrium effects which make labor scale invariant. That doesn’t address the alleged coding errors. We’ll see – and perhaps I wrote an autopsy too early. Thanks to Bryan Caplan for getting Hsieh’s response out to the world. Popular urban econ should be shaken with the revelation that its most famous academic paper had two coding errors, a serious theoretical flaw, and a hypothesized mechanism that – when executed correctly – did not work at all. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti’s paper Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation noted that “high productivity cities like New York and the San Francisco Bay Area have adopted stringent restrictions to new housing supply, effectively limiting the number of workers who have access to such high productivity” – and used a simple model to estimate how much US growth could have been unlocked by decreasing those restrictions. Brian Greaney, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, released notes on his replication of The paper gained widespread notice as a 2015 NBER working paper and was published in 2019 in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. The paper already has an impressive 813 scholarly citations. But the paper has problems – fatal problems – and is embarrassingly sloppy. The embarrassment extends beyond the authors to the many referees and editors who missed surface, implementation, architectural, and foundational problems over a four-year period of peer review and discussion. Surface Greaney is not the first to find a mistake in Hsieh & Moretti. Bryan Caplan caught a major inconsistency in 2021, one that readers (myself included) and referees should have caught earlier. The authors reported huge annual effects adding up to a merely-large effects over 45 years. He noted a few other arithmetical mistakes and generously concluded, “authors and referees […]

While doing some research for an article about driverless trains, I came across this document by Mircea Georgescu (who most recently worked at Thales [I think?] and whose email I can’t track down! Mircea, if you’re reading this, trimite-mi si mie te rog frumos un email la [email protected]!), that’s a sort of primer on CBTC and its application in driverless train operation. The paper is very short as far as these things go, and surprisingly readable, even if Mircea’s English ain’t the best. You can download the PDF here, and here’s the abstract: Reliable driverless operation requires specific features implemented at system and subsystem levels of the train control system. Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC) is now proven as the best choice for driverless systems due to inherent high levels of safety and reliability with a low life cycle cost. This paper proposes a systematic approach that may be used to determine the most efficient way to fulfil the requirements specific to each customer faced with driverless operation (green field or re-signaling). It also defines “must have” requirements (functionality) to obtain the desired performance and cost. The paper also addresses issues related to the operability, maintainability, and availability of different types of driverless CBTC systems implementations, and the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. By the way, the article references another written by Mircea Georgescu and Firth Whitwam called “Moving to Full Automatic Operations,” whose citation is “IEEE Hong Kong 2005.” Anyone know where I could get my hands on this? [email protected], as always!