Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Is it even possible today to write a vigorous argument in favor of the urban renewal policies of the 1950s? I doubt it. Jeanne Lowe's 1967 "Cities in a Race with Time* is a sympathetic account of the urban renewal era in its own terms. How does it hold up?

American YIMBYs point to Tokyo as proof that nationalized zoning and a laissez faire building culture can protect affordability. But a great deal of that knowledge can be traced back to a classic 2014 Urban Kchoze blog post. As the YIMBY movement matures, it's time to go books deep into the fascinating details of Japan's land use institutions.

A major barrier to the market urbanist’s ability to make the case for building more housing is the question of aesthetics. When you refer to density in cities, it’s easy to picture large brutalist towers and the slum-like conditions that can be seen in much of the developing world. Of course, this isn’t what we advocate, but it is a problem we have to repeatedly address. Homeowners, whether we like it or not, are a powerful voter group and they want to live in areas that look nice. Fortunately, the British Government has found the golden mean of housing plans by accepting the results of the Building Better, Building Beautifully Commission.. The key takeaway of this report is street-voting. This represents an excellent middle ground between the seemingly opposite need for housing to be popular, and the need for housing to be plentiful. The current system used in England fails to provide a fair way of measuring public views on plans. This works by assessing the views of nearby residents through a consultation. This allows any resident to attend, or write in, laying out their views on the plan. It may sound democratic, but local consultations are notoriously unrepresentative of a community. Those who take part are overwhelmingly middle-class, property-owning white people who stand to benefit from a housing shortage. Rather than taking into account the views of the local area, this method merely measures the views of those who would be economically burdened by addressing the crisis. The city as a commons What we’re left with is what social scientists would call the tragedy of the commons. This is where you have a common-pool resource where individual use of that resource depletes the stock for other parties. Cities can also be understood to be “the commons” in that they […]

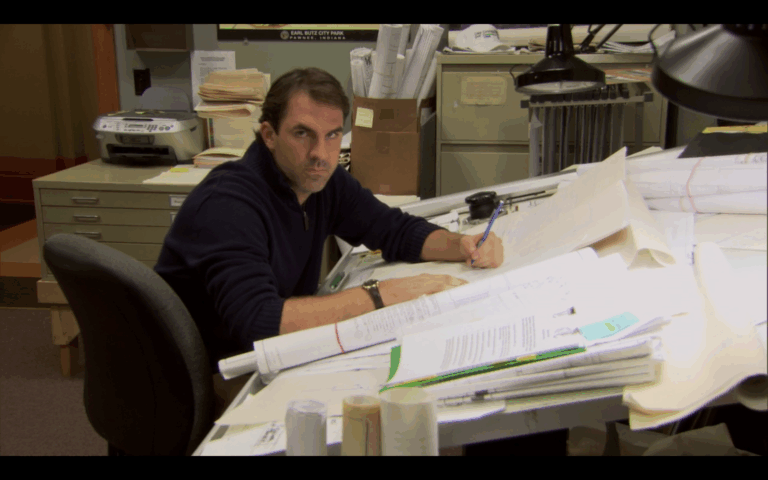

Spoiler Warning: This post contains minor spoilers about Season Two of Parks and Recreation, which aired nearly 10 years ago. Why have you still not watched it? Lately I have been rewatching Parks and Recreation, motivated in part by the shocking discovery that my girlfriend never made it past the first season. The show is perhaps the most sympathetic cultural representation of local public sector work ever produced in the United States. The show manages to balance an awareness of popular discontent with “government” in the abstract— explored through a myriad of ridiculous situations—with the more mild reality that most local government employees are well-meaning, normal, mostly harmless people who care about their communities. This makes the character of Mark Brendanawicz, Pawnee’s jaded planner, all the more interesting. It’s conspicuous that even in a show so sympathetic to local government, the city planner remains a cynical, somewhat unlikable character. Unlike Ron Swanson, Brendanawicz at one point meant well and has no ideological issues with government; he regularly suggests that he was once a true believer in his work, if only for “two months.” Yet unlike Leslie Knope, he didn’t choose government. In his efforts to win back Anne, Andy chides Brendanawicz as a “failed architect,” an insult which seems to stick. Brendanawicz ultimately leaves the show as an unredeemed loser: after taming his apparent self-absorption and promiscuity, he prepares to propose to Anne, only to have her preemptively break up with him. When the government shutdown occurs at the end of Season Two, Brendanawicz takes a buyout offer, and resolves to go into private-sector construction. Leslie, who had once adored him, dubs him “Brendanaquits,” and we never hear from Pawnee’s city planner again. It isn’t hard to see why Brendanawicz was unceremoniously scrapped: he was ultimately a call-back to the harsher world […]

In my regular discussions of U.S. zoning, I often hear a defense that goes something like this: “You may have concerns about zoning, but it sure is popular with the American people. After all, every state has approved of zoning and virtually every city in the country has implemented zoning.” One of two implications might be drawn from this defense of Euclidean zoning: First, perhaps conventional zoning critics are missing some redeeming benefit that obviates its many costs. Second, like it or not, we live in a democratic country and zoning as it exists today is evidently the will of the people and thus deserves your respect. The first possible interpretation is vague and unsatisfying. The second possible interpretation, however, is what I take to really be at the heart of this defense. After all, Americans love to make “love it or leave it” arguments when they’re in the temporary majority on a policy. But is Euclidean zoning actually popular? The evidence for any kind of mass support for zoning in the early days is surprisingly weak. Despite the revolutionary impact that zoning would have on how cities operate, many cities quietly adopted zoning through administrative means. Occasionally city councils would design and adopt zoning regimes on their own, but often they would simply authorize the local executive to establish and staff a zoning commission. Houston was among the only major U.S. city to put zoning to a public vote—a surefire way to gauge popularity, if it were there—and it was rejected in all five referendums. In the most recent referendum in 1995, low-income and minority residents voted overwhelmingly against zoning. Houston lacks zoning to this day. Meanwhile, the major proponents of early zoning programs in cities like New York and Chicago were business groups and elite philanthropists. Where votes were […]

by Samuel R Staley Before the twentieth century land-use and housing disputes were largely dealt with through courts using the common-law principle of nuisance. In essence if your neighbor put a building, factory, or house on his property in a way that created a measurable and tangible harm, courts could intervene on behalf of a complainant to force compensation or stop the action. This pro-property rights approach maximized liberty and minimized the ability of citizens and elected officials to politicize the development process. This changed with the Progressive movement. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Progressives argued that government should become more professional. Rather than being limited, government should use its resources to pursue the “public interest,” loosely defined as whatever the general public decided through democratic processes was the proper scope of government. Legislatures and, by extension, city commissions made up of elected citizens would set policy and goals while a cadre of trained professionals would use the techniques of scientific management to implement policies. One of the leading Progressives of the day, Woodrow Wilson, was skeptical of the value of elected bodies such as Congress because they interfered with scientific management of government. While many in the twenty-first century might be tempted to dismiss this public-interest view of government—indeed an entire academic subdiscipline, Public Choice, has emerged to demonstrate the foibles of governments and explore “government failure”—Progressive ideas held a lot of appeal at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition to national concerns over industries such as oil, steel, and railroads, local governments were rife with corruption, waste, and inefficiency. Reforms, such as the city-manager form of government, civil-service exams, and in some cases even municipal ownership of utilities, were thought to provide more transparency and accountability than the patronage-laden times of political bosses. (Today municipal […]

This week’s column is drawn from a lecture I gave at the University of Southern California on the occasion of the retirement of urban economist Peter Gordon. One of my heroes is the urbanist Jane Jacobs, who taught me to appreciate the importance for entrepreneurial development of how public spaces—places where you expect to encounter strangers—are designed. And I learned from her that the more precise and comprehensive your image of a city is, the less likely that the place you’re imagining really is a city. Jacobs grasped as well as any Austrian economist that complex social orders such as cities aren’t deliberately created and that they can’t be. They arise largely unplanned from the interaction of many people and many minds. In much the same way that Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek understood the limits of government planning and design in the macroeconomy, Jacobs understood the limits of government planning and the design of public spaces for a living city, and that if governments ignore those limits, bad consequences will follow. Planning as taxidermy Austrians use the term “spontaneous order” to describe the complex patterns of social interaction that arise unplanned when many minds interact. Examples of spontaneous order include markets, money, language, culture, and living cities great and small. In her The Economy of Cities, Jacobs defines a living city as “a settlement that generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Living cities are hotbeds of creativity and they drive economic development. There is a phrase she uses in her great work, The Life and Death of Great American Cities, that captures her attitude: “A city cannot be a work of art.” As she goes on to explain: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works […]

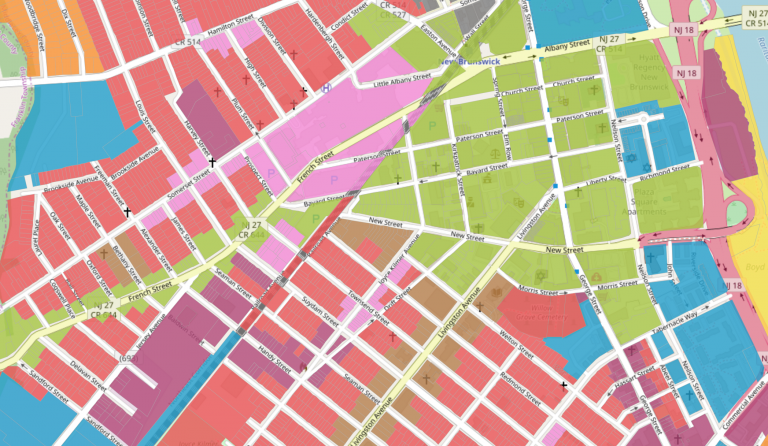

If you regularly read about cities, you might notice that Texas cities rarely seem to come up. We make cases for why Detroit is definitely coming back—just you wait! We come up with elaborate theories of how cities can become the next Silicon Valley. We spend hours coming up with a solution to New York City’s costumed panhandler problem. Yet the four urban behemoths of the Lone Star State—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin—remain conspicuously absent from the conversation. Boy, has that changed. Earlier this year I wrote a sprawling defense of Houston. Scott Beyer spent the summer writing a series of articles for Forbes profiling the cool things happening in cities across the state. John Ricco recently launched the “Densifying Houston” Twitter feed and discussed the phenomenon on Greater Greater Washington. Just this past weekend, City Journal released an entire special issue dedicated to Texas. Through all this, many have been surprised to learn that a city like Houston could serve as a model for land-use policy and economic growth for struggling coastal cities. Yet two criticisms regularly seem to come up, at least related to Houston: “Houston is an unplanned hell-hole! It’s proof that land-use liberalization would be a disaster.” “Houston isn’t unplanned! It’s as heavily planned as any other city, just look at the covenants.” Since there seems to be a lot of confusion about land-use regulation and planning in Houston, here’s a quick explainer on what Houston does regulate, doesn’t regulate, and how private covenants shape the city. 1. What Houston Doesn’t Do Houston doesn’t mandate single-use zoning. Unlike every other major U.S. city, Houston doesn’t mandate the separation of residential, commercial, and industrial developments. This means that restaurants, homes, warehouses, and offices are free to mix as the market allows. As many have pointed out, however, market-driven separation of incompatible uses—think […]

Several cities have jumped on the bandwagon of building Micro-apartments, a hot trend in apartment development. San Francisco and Seattle already have them. New York outlawed them, but is testing them on one project, and may legalize them again. Even developers in smaller cities like Denver and Grand Rapids are taking a shot at micro-apartments. At the same time, Chicago is building lots of apartments, and is known for having low barriers to entry for downtown development. Yet we aren’t hearing of much new construction of micro-apartments here. Premier studios are fetching as much as $2,000 a month. Certainly there must be demand for something more approachable to young professionals. In theory, we should expect to see Chicago leading the way in innovative small spaces. Chicago doesn’t have an outright ban on small apartments like New York, but there are four regulatory obstacles in the Chicago zoning code. These are outdated remnants from eras where excluding undesirable people were main objectives of zoning, and combined to effectively prohibit small apartments: 1. Minimum Average Size: Interestingly, there is no explicit prohibition of small units. This is unlike New York City’s zoning, which prohibits units smaller than 400sf. There is, however, a stipulation that the average gross size of apartments constructed within a development be greater that 500sf. Assuming 15% of your floor-plate is taken by hallways, lobbies, stairs, etc; this means for every 300sf unit, you need one 550sf unit to balance it out. Source: 17-2-0312 for residential; 17-4-0408 for downtown 2. Limits on “Efficiency Units”: Zoning stipulates a minimum percentage of “efficiency units” within a development. The highest density areas downtown allow as much as 50%, but these are the most expensive areas where land is most expensive. In areas traditionally more affordable, the ratio is as low as 20% to discourage studios, and encourage […]

Turn the lights down, and the volume up. It's time for some Market Urbanist media, courtesy of some future urbanist leaders who's ideas may one day liberate our cities from yesterday's authoritarian planners.