Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

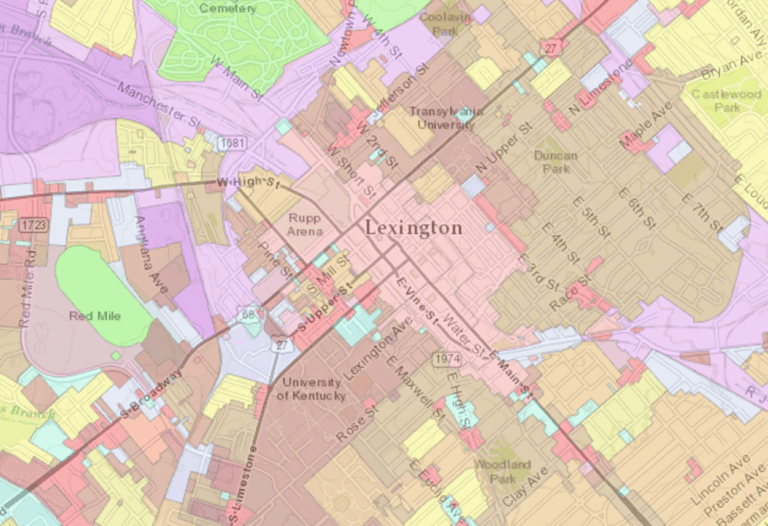

Lexington, Kentucky is a wonderful place, and that’s getting to be a problem. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the city: its urban amenities, thriving information economy, and unique local culture have brought in throngs of economic migrants from locales as exotic as Appalachia, Mexico, and the Rust Belt. The problem, rather, is that the city isn’t zoned to support this newfound attention. Over the past five years, the city has grown by an estimated 18,000 residents, putting Lexington’s population at approximately 314,488. Lexington has nearly tripled in size since 1970 and the trend shows no signs of stopping, with an estimated 100,000 new residents arriving by 2030. Despite this growth, new development has largely lagged behind: despite the boom in new residents, the city has only permitted the construction of 6,021 new housing units over the past five years—not an awful ratio when compared to a San Francisco, but still putting us firmly on the path toward shortages. The lion’s share of this new development has taken the form of new single-family houses on the periphery of town. Create your own infographics. Sources: ACS/Census Bureau At the risk of sounding like a broken record, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with single-family housing on the periphery of town. Yet in the case of Lexington, it’s suspect as a sustainable source of affordable housing. Lexington was the first American city to adopt an urban growth boundary (UGB), a now popular land-use regulation that limits outward urban expansion. As originally conceived, the UGB program isn’t such a bad idea: the city would simultaneously preserve nearby farmland and natural areas (especially important for Lexington, given our idyllic surrounding countryside) while easing restrictions on infill development. Create your own infographics. Source: Census Bureau The trouble with Lexington is that the city has undertaken […]

Washington, D.C. has a monopoly on many things. Bad policy, unfortunately, isn’t among them. Last month, a development corporation in Lexington, Kentucky installed a shipping container house in an economically distressed area of town to improve housing affordability. The corporation is a private non-profit, though a line near the end of this article indicates that the project received public support: “The project is funded through an assortment of grants from the city’s affordable housing fund [and two philanthropic organizations].” Shipping container projects designed to improve housing affordability aren’t limited to my Old Kentucky Home: a quick Google search reveals that the idea of using shipping containers to put a dent in housing costs is popular among policymakers and philanthropists all over the world. The sad reality is that shipping container homes likely have little—if any—role to play in handling the nationwide housing affordability problem. Aside from being inefficient for housing generally, there’s decent evidence that shipping containers appeal far more to reasonably well-off, single urbanites than to working families in need of affordable housing. More broadly, the belief that these projects could address the growing affordability crisis hints at a profound misunderstanding of the nature of the problem and distracts policymakers from viable solutions. Before digging into the meatier problems, it’s worth looking first at the problems with the structures themselves. I’ll yield to an architect: Housing is usually not a technology problem. All parts of the world have vernacular housing, and it usually works quite well for the local climate. There are certainly places with material shortages, or situations where factory built housing might be appropriate—especially when an area is recovering from a disaster. In this case prefab buildings would make sense—but doing them in containers does not. The source goes on to detail the enormous costs associated with zoning approval, insulation, and utilities. Then there’s the somewhat obvious fact that they’re small. As in, 144 square […]