Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

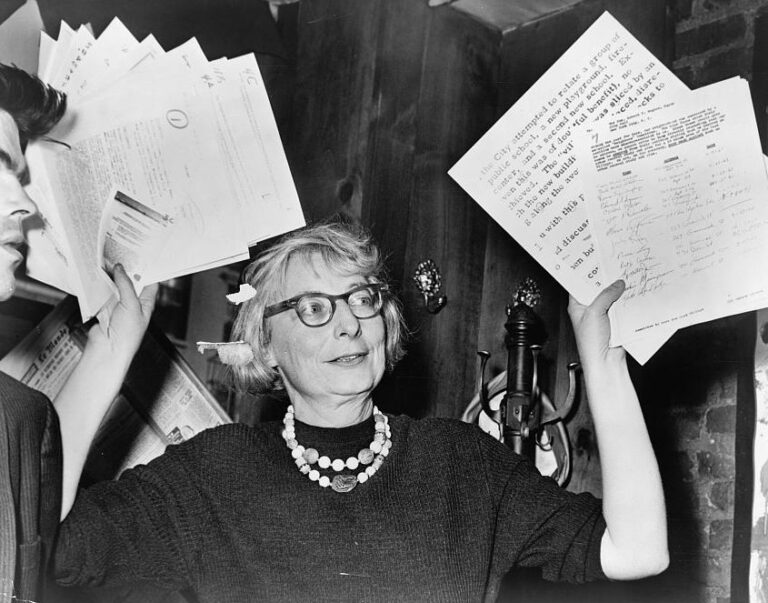

The starting point for Jacobs’s analysis and the focus of much of her thought is the city, its nature and significance. There are plenty of books out there that in some way celebrate cities. Many describe cities as engines of economic development, wellsprings of art and culture, and incubators of ideas religious, social, and scientific. But few go very far in explaining why and how all that usually happens in a city. Fewer still view the urban processes as expressions of “emergence,” or what some social theorists describe using the related term “spontaneous order.” That is the perspective of this book and its main contribution: To look closely at what makes a city a spontaneous order and an engine of innovation, and to trace the analytical and policy consequences of viewing it this way. Jane Jacobs is one of those exceptions, indeed an outstanding one. In fact, she is probably the first to carefully examine, not only the nature and significance of cities, but to distill realistic principles that govern urban systems and to analyze the mechanisms of economic change that follow from those principles. Her analysis of the relation between the design of public space and social interaction offer insights that complement, and often exceed, those of Max Weber, Henri Pirenne, Georg Simmel (pdf), Kevin Lynch, and others. Her work also has deep connections with modern social theorists such as F.A. Hayek, Elinor Ostrom, Mark Granovetter, and Geoffrey West. But she was not the first to develop conceptual tools congenial to understanding urban processes as emergent, spontaneous orders. In fact they have largely been available for decades in the field of economics, although few professional economists, including urban economists, have fully appreciated the urban origins of many of their standard concepts and tools of analysis. Indeed, there is a […]

Welcome to the first post in Culture of Congestion! I’ll be posting quotes, ideas, and short essays relating to a book I’m writing, which I might describe as “What I have learned from the economic and social theory of Jane Jacobs.” My hope is to get thoughtful, informed feedback that will be useful in shaping the book. – Sandy Ikeda When I asked Jane Jacobs what she believed her main intellectual contribution was, she answered without hesitation, “Economic theory!” It’s been my experience that most of those who admire Jacobs for her trenchant writings and fierce activism against heavy handed urban planning and top-down urban design find it surprising that she thought of herself at heart as an economist. But a glance at the titles of her books makes this rather obvious: The Economy of Cities, Cities and the Wealth of Nations, and The Nature of Economies. And in her most famous book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she explains in intricate detail a la modern social theory what social institutions and norms enable people to discover and pursue their plans at street level, and how doing so allows the city in which they are embedded to flourish in unpredictable ways. She understood how creative innovation – in commerce, science and technology, and culture – is central to that flourishing. She explained, in a way that rivals or surpasses most economic theorists, how and under what conditions innovation takes place and how that tends to undermine attempts at central planning at the local level. One of my motivations for writing this book is to make Jane Jacobs, economist, better known especially to those who already rightly admire her for the other contributions she has made as a public intellectual, and to trace her criticisms of urban planning and design and of various public […]

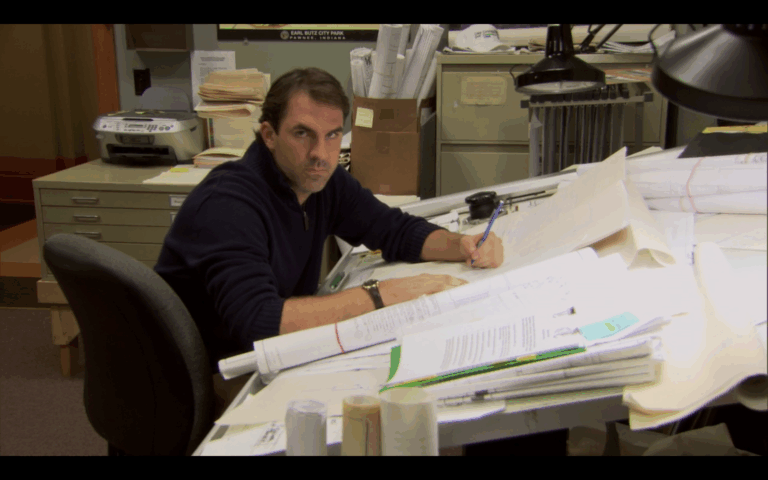

Spoiler Warning: This post contains minor spoilers about Season Two of Parks and Recreation, which aired nearly 10 years ago. Why have you still not watched it? Lately I have been rewatching Parks and Recreation, motivated in part by the shocking discovery that my girlfriend never made it past the first season. The show is perhaps the most sympathetic cultural representation of local public sector work ever produced in the United States. The show manages to balance an awareness of popular discontent with “government” in the abstract— explored through a myriad of ridiculous situations—with the more mild reality that most local government employees are well-meaning, normal, mostly harmless people who care about their communities. This makes the character of Mark Brendanawicz, Pawnee’s jaded planner, all the more interesting. It’s conspicuous that even in a show so sympathetic to local government, the city planner remains a cynical, somewhat unlikable character. Unlike Ron Swanson, Brendanawicz at one point meant well and has no ideological issues with government; he regularly suggests that he was once a true believer in his work, if only for “two months.” Yet unlike Leslie Knope, he didn’t choose government. In his efforts to win back Anne, Andy chides Brendanawicz as a “failed architect,” an insult which seems to stick. Brendanawicz ultimately leaves the show as an unredeemed loser: after taming his apparent self-absorption and promiscuity, he prepares to propose to Anne, only to have her preemptively break up with him. When the government shutdown occurs at the end of Season Two, Brendanawicz takes a buyout offer, and resolves to go into private-sector construction. Leslie, who had once adored him, dubs him “Brendanaquits,” and we never hear from Pawnee’s city planner again. It isn’t hard to see why Brendanawicz was unceremoniously scrapped: he was ultimately a call-back to the harsher world […]

Sandy Ikeda has led a Brooklyn Heights Jane’s Walk every year since 2011 in celebration of Jane Jacobs’ 101st birthday. Meet at the steps of Borough Hall (facing the Plaza and fountain) Sunday May 7th at 12:15. When you think of a city you like, what comes to mind? Can a city be a work of art? How do parked cars serve pedestrians? Most of the interaction among people, bikes, and cars is unplanned. How does that happen? Why do people gather in some places and avoid others? Is it possible to create a neighborhood from the ground up? What is a “public space”? How can the design of public space promote or retard social interaction? The beautiful and historic neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights offers excellent examples of Jane Jacobs’s principles of urban diversity in action. Beginning at the steps of Brooklyn¹s Borough Hall, we will stroll through residential and commercial streets while observing and talking about how the physical environment influences social activity and even economic and cultural development, both for good and for ill. We will be stopping at several points of interest, including the famous Promenade, and end near the #2/3 subway and a nice coffeehouse. To Find a Jane’s Walk near you, visit http://janeswalk.org/

No one writer of the last 60 years has influenced urban planning and thinking as much as Jane Jacobs. It seems like just about everyone who has ever set foot in a major city has read The Death and Life of Great American Cities and most professional urban planners have embraced at least part of her ideas. But that was not the only book she wrote and the others deserve attention from urbanists. First published in 1984, Cities and the Wealth of Nations was her last book to focus on cities and her second concerned with economics. Conceived at the height of 1970s stagflation, Jacobs brought her considerable polemical skills to bear on macroeconomics and elaborated on the observations in The Economy of Cities. In that book she theorized that economic expansion in cities was driven by trade, innovation and imitation in a process she called “import replacement”. In this one she extended the idea, arguing that cities and not nation-states are the real basic units of macroeconomic life. She also examined how the economic expansion affected regions in differing geographic proximity and how import-replacement and the wealth generated by it can be used in ways that ultimately undermine the abilities of cities to create wealth, which she called transactions of decline. Import-replacement is one of Jacobs’ more controversial ideas, partially because it seems similar to a discredited development policy called import substitution and partially because her evidence is largely anecdotal, as Alon Levy wrote back in 2007. Nevertheless it’s the centerpiece of Jacobs’ economic theories. And dismissing her work based on a lack of conventional credentials ignores her entire rise to fame and influence. Two important things distinguish import-replacement from import-substitution. Substitution is a national policy pursued by governments with taxes, tariffs and subsidies while replacement is a process […]

It is because every individual knows little and, in particular, because we rarely know which of us knows best that we trust the independent and competitive efforts of many to induce the emergence of what we shall want when we see it. — Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty Imagine the perfect city. If you have a clear picture in mind, you’re not alone. Tsars, emperors, and prophets have been trying to build perfect cities for millennia. With the emergence of the field of urban planning and modern social science, everyone from stenographers to industrialists to independent architects have joined in. For Ebenezer Howard, the perfect city was the Garden City, a corporate-owned residential satellite on the outer edge of town. For Le Corbusier, it was the Ville Radieuse, full of “skyscrapers in the park” and elevated highways. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was Broadacre City, a dispersed anti-city full of single-family homes on one-acre lots. Each reflects a distinct vision of urban life, and each seems to have as many opponents as it does proponents. Thankfully, few of these plans have ever been implemented in full on a mass scale. Yet “perfect city” thinking—the view that one particular vision of urban form should be imposed by planners—has manifested itself in small ways in cities around the world through the construction and enforcement of specific theories of how a city should work. This approach to urban form involves expanding urban planning beyond prudentially managing infrastructure and mitigating destructive negative externalities and toward enforcing and preserving particular lifestyle and aesthetic preferences. Consider: while Ville Radieuse was never built, many cities bulldozed traditional urban neighborhoods to construct the urban elevated highways of Le Corbusier’s dreams. While Broadacre City never moved beyond the model stage, many suburban communities still zone minimum lot sizes […]

This week on the Market Urbanism Podcast, I chat with Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring on the wonderful new volume Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs. From Jacobs’ McCarthy-era defense of unorthodox thinking to snippets of her unpublished history of humanity, the book is a must-read for fans of Jane Jacobs. In this podcast, we discuss some of the broader themes of Jacobs’ thinking. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Pick up your copy of Vital Little Plans on Amazon. Mentioned in the podcast, Manuel DeLanda discusses Jane Jacobs in A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. Read more about the West Village Houses here. The question of Quebec separatism is a fascinating—and under-considered—element of Jacobs’ work. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

My guest this week is Sanford Ikeda, a professor of economics at SUNY Purchase and a visiting scholar at New York University. He has written extensively on urban economics, policy, and planning. Professor Ikeda introduced me to urban economics and urban planning when he gave a presentation on Jane Jacobs at a FEE summer seminar that I attended back in 2012. Here are a few of the topics we discussed in the episode: If you haven’t already, I highly suggest reading Jane Jacobs. The natural place to start is The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Her other books, including The Economy of Cities and Systems of Survival, explore topics ranging from economics to political philosophy. Professor Ikeda has written extensively on Jane Jacobs. You can read a nice overview here. If you would like to read more, click here for a paper he wrote on F.A. Hayek, Jane Jacobs, and the importance of local knowledge in cities. He is also a regular contributor to Freeman and Market Urbanism. We also discussed William H. Whyte’s famous documentary on public space, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. It’s well worth checking out. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

This week’s column is drawn from a lecture I gave at the University of Southern California on the occasion of the retirement of urban economist Peter Gordon. One of my heroes is the urbanist Jane Jacobs, who taught me to appreciate the importance for entrepreneurial development of how public spaces—places where you expect to encounter strangers—are designed. And I learned from her that the more precise and comprehensive your image of a city is, the less likely that the place you’re imagining really is a city. Jacobs grasped as well as any Austrian economist that complex social orders such as cities aren’t deliberately created and that they can’t be. They arise largely unplanned from the interaction of many people and many minds. In much the same way that Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek understood the limits of government planning and design in the macroeconomy, Jacobs understood the limits of government planning and the design of public spaces for a living city, and that if governments ignore those limits, bad consequences will follow. Planning as taxidermy Austrians use the term “spontaneous order” to describe the complex patterns of social interaction that arise unplanned when many minds interact. Examples of spontaneous order include markets, money, language, culture, and living cities great and small. In her The Economy of Cities, Jacobs defines a living city as “a settlement that generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Living cities are hotbeds of creativity and they drive economic development. There is a phrase she uses in her great work, The Life and Death of Great American Cities, that captures her attitude: “A city cannot be a work of art.” As she goes on to explain: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works […]

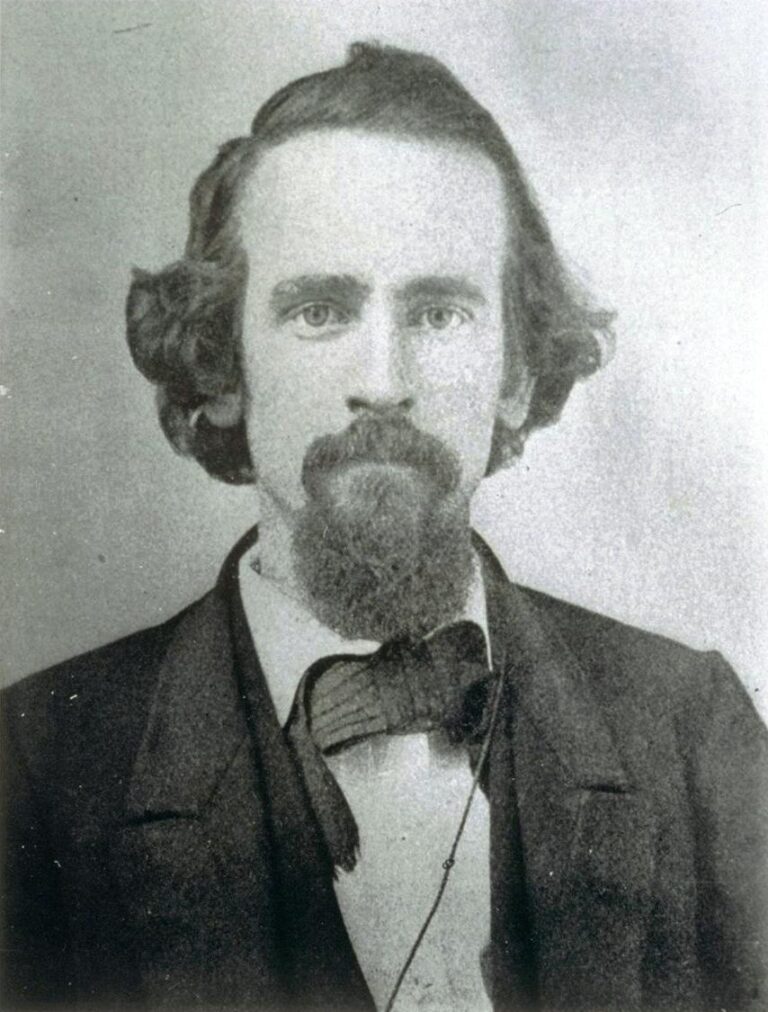

Henry George and Jane Jacobs each have an enthusiastic following today, including, I’m sure, some readers of The Freeman. For those who might not know, Henry George is the late-19th-century American intellectual best known for his proposal of a “single tax” from which he believed the government could finance all its projects. He advocated eliminating all taxes except that on the rent of the unimproved portion of land. He viewed that rent as unjust and solely the result of general economic progress unrelated to the actions of landowners. Jane Jacobs, writing about one hundred years later, is an American intellectual best known for her harsh and incisive criticism of the heavy-handed urban planning of her day. She advised ambitious urban planners to first understand the microfoundations of urban processes — street life, social networks, entrepreneurship — before trying to impose their visions of an ideal city. Much has been written, pro and con, on George’s single tax and also on Jacobs’s battles with planners the likes of Robert Moses, and if you’re interested in those issues you can start with the links provided in this article. Here I would like to contrast their views on the nature of economic progress and the significance of cities in that progress. Some interesting parallels There are some interesting parallels between George and Jacobs. Both were public intellectuals who rebelled against mainstream economic thinking — for George it was classical economics, for Jacobs neoclassical economics. Both had a firm grasp of how markets work, were critical of crony capitalism, and concerned with the problems of “the common man.” And both established their reputations outside of academia. George was a strong advocate for free trade and an opponent of protectionism. He also understood Adam Smith’s explanation of the invisible hand. As George writes in […]