Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In my day job, I suggested the name “Urbanity” for the research project that Emily Hamilton and I co-lead. I wasn’t sure about it myself, but it stuck. The noun urbanity, of course, refers both to the quality of being…

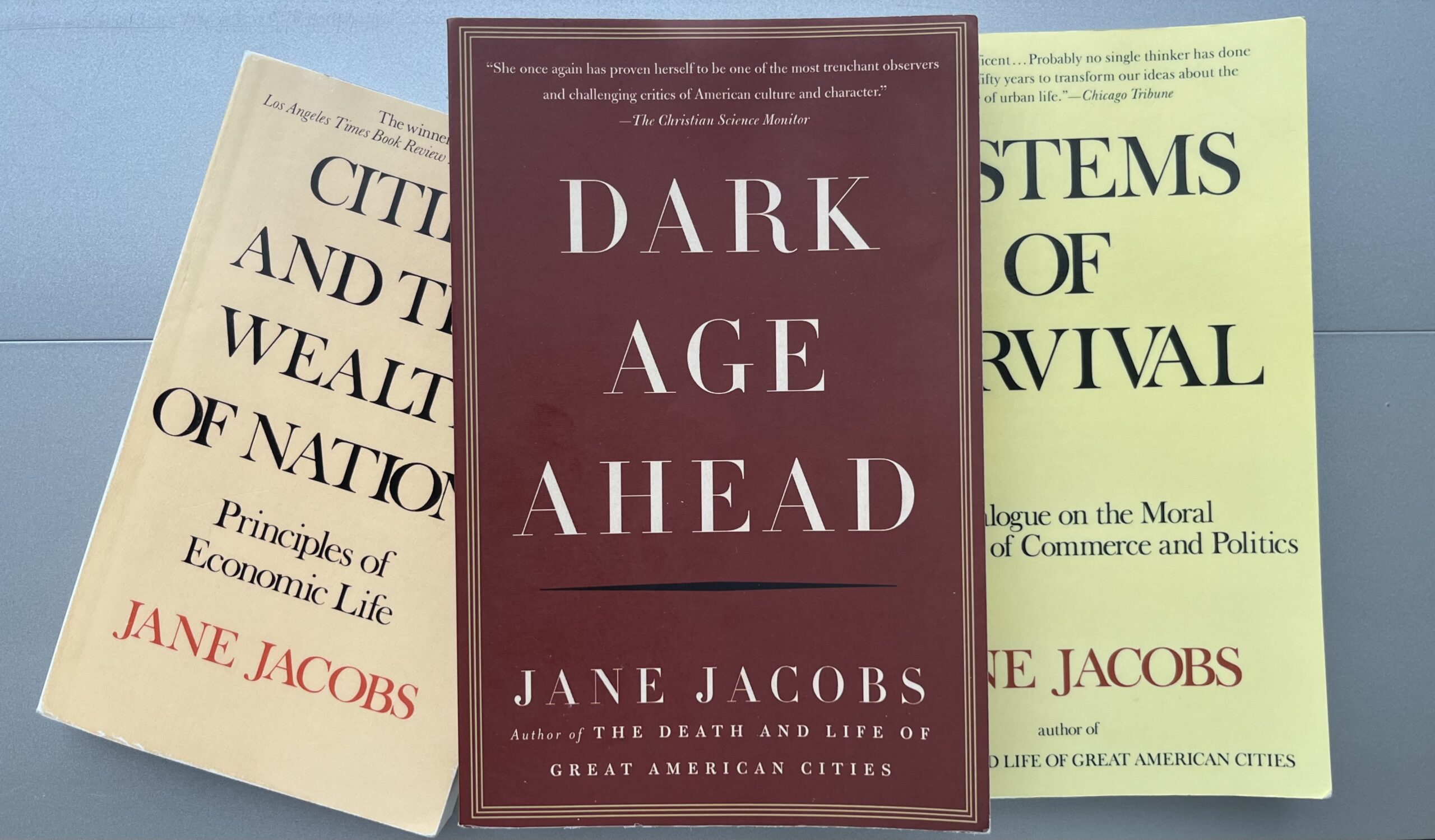

Jane Jacobs wasn’t optimistic about the future of civilisation. ‘We show signs of rushing headlong into a Dark Age,’ she declares in Dark Age Ahead, her final book published in 2004. She evidences a breakdown in family and civic life, universities which focus more on credentialling than on actually imbuing knowledge in its participants, broken feedback mechanisms in government and business, and the abandonment of science in favour of ‘pseudo-scientific’ methods. Jacobs’ prose is, as always, rich, convincing and successful in making the reader see the importance of her claims. Yet the argument that we are spiralling into a new Dark Age, similar to that which followed the fall of the Roman Empire, is not quite complete and I remain unconvinced that the areas she identified point towards collapse as opposed to merely things we could, and should, work to improve. Let us start with the idea that families are ‘rigged to fail,’ as she puts it in chapter two. Jacobs, urbanist at heart, cites ‘inhumanely long car commutes’ stemming from the disbanding of urban transit systems, rising housing costs, and a breakdown in ‘community resources’ – the result of increasingly low-dense forms of urban development – as a significant reason why families are now set up for failure. She suggests our days are filled with increasingly vacuous activities, leading to the rise of ‘sitcom families’ which ‘can and do fill isolated hours’ at the expense of ‘live friends.’ That phenomenon has now been replaced by the ‘smartphone family’ where time spent on TikTok, and consuming other forms of digital media have supplanted the ‘sitcom’ family of the past. There has been significant literature on the detrimental effects of digital technologies to our physical and mental health, not least in Jonathan Haidt’s most recent book, The Anxious Generation. A similar picture is painted by Timothy Carney in […]

Continuing this series of book reviews on Jane Jacobs’ works, I now turn to Cities and the Wealth of Nations. But there is already a fantastic piece on the Market Urbanism website, by Matthew Robare, who reviews this book and outlines what Jacobs overlooks in her analysis. So, this piece takes a slightly different angle: inspired by (but not limited to) Jacobs’ ideas, it aims to highlight what mayors, governors and urban policymakers could do differently if they are serious about developing their cities into economic powerhouses. Here are some of the most important takeaways from this book and also how they can be expanded upon. (1) Focus on cultivating import-replacement The economies of cities do not grow out of nothing. They grow by adding productive new forms of work to old ones, by innovating, and by being cultivators of new ideas and techniques. This process of cataclysmic growth – that Jane Jacobs describes as ‘import-replacement – occurs when a city takes its existing imports and builds upon them, either improving its production through lowering costs, increasing quality, or innovating. The market for these additional goods can either be found within the city itself or serves to expand the city’s exports. These exports, in turn, bring in additional resources to either acquire additional imports or be reinvested into fuelling the processes that fuel import-replacement. Not for nothing does Jacobs describe import-replacement as a ‘cataclysmic’ process – these changes often happen over a very short period and can bring about a rapid influx of people, ideas and capital. We see this in New York City, which grew from half a million residents in 1850 to over 3.4 million at the dawn of the twentieth century. Detroit went from having 250,000 residents in 1900 to a peak of 1.8 million by 1950. […]

At the heart of Jane Jacobs’ The Economy of Cities is a simple idea: cities are the basic unit of economic growth. Our prosperity depends on the ability of cities to grow and renew themselves; neither nation nor civilisation can thrive without cities performing this vital function of growing our economies and cultivating new, and innovative, uses for capital and resources. It’s a strikingly simple message, yet it’s so easily and often forgotten and overlooked. Everything we have, we owe to cities. Everything. Consider even the most basic goods: the food staples that sustain life on earth and which in the affluent society in which we now reside, abound to the point where obesity has become one of the leading causes of illness. Obesity sure is a very real problem and one we ought to work to resolve (probably through better education and cutting those intense sugar subsidies). Yet this fact alone is striking! For much of mankind’s collective history, the story looked very different: man (and it usually was a man) would spend twelve or maybe more hours roaming around in the wild to gather sufficient food to survive. Our lives looked no different to the other animals with which we share the earth. An extract from The Economy of Cities: ‘Wild animals are strictly limited in their resources by natural resources, including other animals on which they feed. But this is because any given species of animal, except man, uses directly only a few resources and uses them indefinitely.’ What changed? Anthropologists, economists, and historians will tell you it was the Agricultural Revolution, which occurred when man began to settle in small towns and cultivate the agricultural food staples that continue to make up the bulk of our diet: wheat, barley, rice, corn, and animal food products. But […]

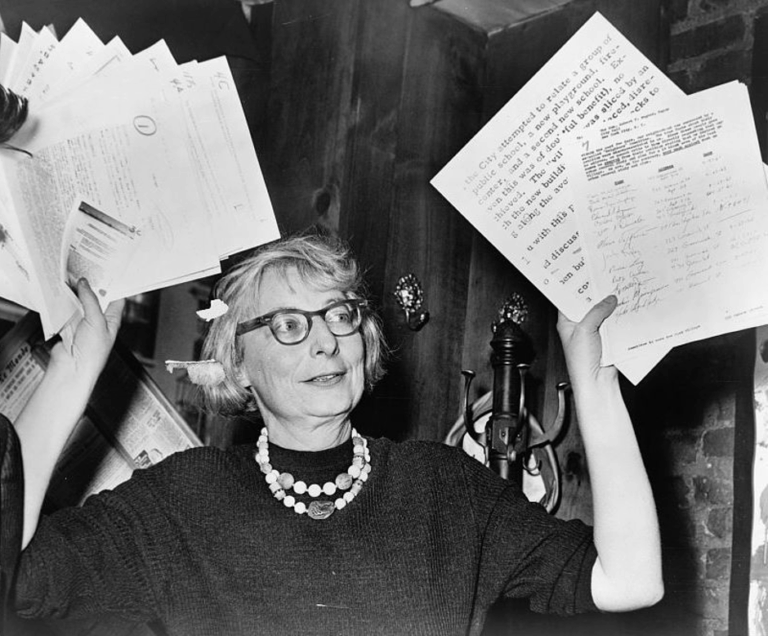

Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, revolutionised urban theory. This essay kicks off a series exploring Jacobs’ influential ideas and their potential to address today’s urban challenges and enhance city living. Adam Louis Sebastian Lehodey, the author of this collection of essays, studies philosophy and economics on the dual degree between Columbia University and SciencesPo Paris. Having grown up between London and Paris, he is energised by the questions of urban economics, the role of the metropolis in the global economy, urban governance and cities as spontaneous order. He works as an Applied Research Intern at the Mercatus Center. Since man is a political animal, and an intensely social existence is a necessary condition for his flourishing, then it follows that the city is the best form of spatial organisation. In the city arises a form of synergy, the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, for the remarkable thing about cities is that they tap into the brimming potential of every human being. In nowhere but the city can one find such a variety of human ingenuity, cooperation, culture and ideas. The challenge for cities is that they operate on their own logic. Cities are one of the best illustrations of spontaneous order. The city in history did not emerge as the result of a rational plan; rather, what the city represents is the physical manifestation of millions of individuals making decisions about where to locate their homes, carry out economic transactions, and form intricate social webs. This reality is difficult to reconcile with our modern preference for scientific positivism and rationalism. But for the Polis to flourish, it must be properly understood by the countless planners, reformers, politicians and the larger body of citizens inhabiting the space. Enter Jane […]

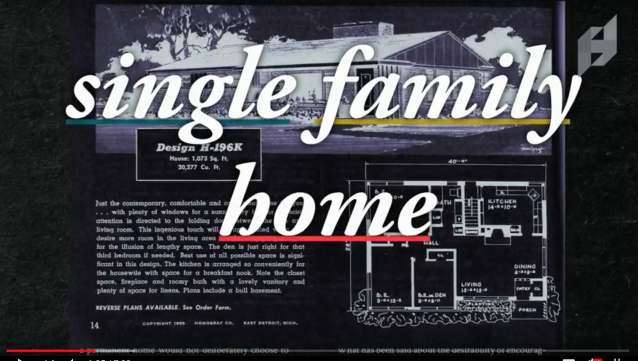

We are blessed and cursed to live in times in which most smart people are expected to have an opinion on zoning. Blessed, in that zoning is arguably the single most important institution shaping where we live, how we move around, and who we meet. Cursed, in that zoning is notoriously obtuse, with zoning ordinances often cloaked in jargon, hidden away in PDFs, and completely different city-to-city. Given this unusual state of affairs, I’m often asked, “What should I read to understand zoning?” To answer this question, I have put together a list of books for the zoning-curious. These have been broken out into three buckets: “Introductory” texts largely lay out the general challenges facing cities, with—at most—high-level discussions of zoning. Most people casually interested in cities can stop here. “Intermediate” texts address zoning specifically, explaining how it works at a general level. These texts are best for people who know a thing or two about cities but would like to learn more about zoning specifically. “Advanced” texts represent the outer frontier of zoning knowledge. While possibly too difficult or too deep into the weeds to be of interest to most lay observers, these texts should be treated as essential among professional planners, urban economists, and urban designers. Before I start, a few obligatory qualifications: First, this not an exhaustive list. There were many great books that I left out in order to keep this list focused. Maybe you feel very strongly that I shouldn’t have left a particular book out. That’s great! Share it in the comments below. Second, while these books will give you a framework for interpreting zoning, they’re no substitute for understanding the way zoning works in your specific city. The only way to get that knowledge is to follow your local planning journalists, attend local […]

It’s an understatement to say that zoning is a dry subject. But in a new video for the Institute for Humane Studies, Josh Oldham and Professor Sanford Ikeda (a regular contributor to this blog) manage to breath new life into this subject, accessibly explaining how zoning has transformed America’s cities. From housing affordability to mobility to economic and racial segregation to the Jacobs-Moses battle, they hit all the key notes in this succinct new video. If you need a go-to explainer video for the curious new urbanists, this is the one. Enjoy!

At first blush, the enterprise of interpreting the Jane Jacobs’ work might seem like one best left to the proud and peculiar few, or to put it less charitably, those of us with nothing better to do. Yet the forces of history militate against this apathy: Jane Jacobs has emerged as quite possibly the most important figure in North American urban planning in the second half of the twentieth century. Her work is now taught in every urban theory and urban planning program worth its weight in ESRI access codes. She is responsible for introducing hundreds of thousands of people to planning and urbanism (including this author) and continues to shape how many of us think about cities. In one of my more popular blog posts here on Market Urbanism—and in a forthcoming book chapter—I argue that we should interpret Jane Jacobs as a spontaneous order theorist in the tradition of Adam Smith, Michael Polanyi, and F.A. Hayek. Built into her work is a profound appreciation of the importance of local knowledge, decentralized planning, and the spontaneous orders that structure urban life. Needless to say, this is not the prevailing interpretation of the importance and meaning of Jacobs’ work. Two very different alternative interpretations prevail. In this post, I argue that both interpretations are mistaken. Jane Jacobs, Form-Based Coder Many have taken Jacobs’ particular critiques of conventional U.S. zoning, often referred to as “Euclidean zoning,” as motivating a new form of zoning that takes into account her observations on design. In contrast to the mandates of Euclidean zoning, which proscribes land-use segregation and low densities, Jacobs celebrated mixtures of land uses and urban densities. Jacobs spends large sections of Death and Life discussing in detail particular urban designs that she sees as essential to fostering urban life. Much of “Part One” focuses on […]

One of the popular sports broadcasts I used to watch as a kid promised interviews with athletes that would bring them to you “up close and personal.” As I was once waiting in line to order coffee at one of my favorite local coffeehouses there were several people ahead of me. I followed the “barista” taking orders, with his dark-framed glasses, reddish beard, and slightly hurried manner. From a distance, in those few minutes I formed an expectation about his personality: Blasé and probably a bit curt; someone who really doesn’t want to be here. But when I came face-to-face with him and placed my order, I could feel his liveliness, warmth, and friendliness. My expectations needed revising. It’s the same with cities. From a distance, from an airplane or a photograph, we notice macro features and sweeping patterns that might form our first impressions. Noticing the layout of streets or the pattern of buildings from the air we might say something like “Oh, what an impressive skyline!” or “This place is a dump!” For instance, New York, London, Paris have distinct skylines. Approaching these cities from the air is thrilling as we spot the Empire State Building dominating Midtown Manhattan, Big Ben and Parliament along the Thames, or the Eiffel Tower standing counterpoint to la Defense. Tokyo’s on the other hand is a different story, but that difference is informative. Tokyo’s skyline is, at least to me, terribly underwhelming. Heavily bombed and burned during World War II and subject to devastating earthquakes throughout its history, Tokyo has few tall buildings compared to other major cities. Even as you drive in closer along the highway from Narita Airport the architecture for the most part remains boxy and drab. When you actually enter the central city, with the Sumida River winding […]

[In this space I’ll be posting quotes, ideas, and excerpts relating to a book I’m writing (thus far untitled), which I might describe as “What I have learned from the economic and social theory of Jane Jacobs.” My hope is to get thoughtful, informed feedback that will be useful in shaping the book.] Architects and planners refer to something called the “built environment” by which they usually mean things such as city streets and pathways and the grids made up by them, buildings of various kinds, plazas, the infrastructure of water and energy inflow and outflow, parks and recreation areas, unbuilt open spaces. Although parts of each of these urban elements were consciously constructed, usually by a team of individuals, the way that they fit together, except in the case of mega- and giga-projects, are not the result of a deliberate plan. Buildings in a particular location, for example, – offices, schools, residences, retail, malls, entertainment, places of worship, research facilities – are of different vintages, constructed by different people for different purposes at different times with different techniques, historical contexts, and sensibilities. But the way they all more-or-less complement one another, their “fit,” is an emergent, unplanned phenomenon. I will refer to these elements collectively as the “built framework,” where the word “built” should not in all cases imply deliberate design. What goes on within the built framework can also be planned or unplanned There are, of course, the activities for which a particular element is intended (most recently, that is, because spaces can have multiple uses over time). A gas station, what we might call a “specialized space,” is primarily for pumping gas, not for seeing a football game, which you do at a stadium. But there are other activities that take place in or are facilitated by a given element, […]