Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

This week on the Market Urbanism Podcast, I chat with Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring on the wonderful new volume Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs. From Jacobs’ McCarthy-era defense of unorthodox thinking to snippets of her unpublished history of humanity, the book is a must-read for fans of Jane Jacobs. In this podcast, we discuss some of the broader themes of Jacobs’ thinking. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Pick up your copy of Vital Little Plans on Amazon. Mentioned in the podcast, Manuel DeLanda discusses Jane Jacobs in A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. Read more about the West Village Houses here. The question of Quebec separatism is a fascinating—and under-considered—element of Jacobs’ work. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

HUD has released 2015 building permit tallies. Austin’s tallies for 2015: Single Family Units: 2,846 Duplex units: 326 Units in 3-4 unit buildings: 30 Units in 5+ unit buildings: 6,890 This bipolar split is typical of American cities. Some cities build more single-family than multi-family. Some build more multi-family than single-family. But the fourplex is dead. We build very little small-scale multi-family these days, which is why the “missing middle” is a focus of zoning code rewrites and a meme among the New Urbanist crowd. Although “missing middle” housing could easily be added to established single-family neighborhoods while preserving “neighborhood character,” it is mostly illegal in Austin and most other American cities, at least within the single-family districts, and it is often staunchly resisted by homeowners in older neighborhoods, where the form of housing makes most sense. Some homeowners, in fact, seem to dislike “missing middle” housing more than any other kind of housing. It is worth thinking about why. It is useful to first think about building technologies. After manufactured housing, the simplest, cheapest housing technology is the low-rise, wood-frame construction used in detached single-family homes. Small apartment buildings can be built using essentially the same techniques. Most large suburban apartment projects, in fact, are developed as a cluster of two-three story buildings containing 8-12 units each. These buildings would actually form nice low-rise, urban neighborhoods if they were arranged around a public street grid, but instead they are arranged around parking lots, private drives and landscaped common areas in garden-style developments. The next step up from low-rise, wood-frame technology is the mid-rise apartment building of four to seven stories. This type of development requires elevators (and thus a concrete elevator core) and usually consists of “stick and brick” construction over a concrete podium. It is at least twice as expensive per square foot as similar quality single-family housing — more if it includes structured […]

Henry George and Jane Jacobs each have an enthusiastic following today, including, I’m sure, some readers of The Freeman. For those who might not know, Henry George is the late-19th-century American intellectual best known for his proposal of a “single tax” from which he believed the government could finance all its projects. He advocated eliminating all taxes except that on the rent of the unimproved portion of land. He viewed that rent as unjust and solely the result of general economic progress unrelated to the actions of landowners. Jane Jacobs, writing about one hundred years later, is an American intellectual best known for her harsh and incisive criticism of the heavy-handed urban planning of her day. She advised ambitious urban planners to first understand the microfoundations of urban processes — street life, social networks, entrepreneurship — before trying to impose their visions of an ideal city. Much has been written, pro and con, on George’s single tax and also on Jacobs’s battles with planners the likes of Robert Moses, and if you’re interested in those issues you can start with the links provided in this article. Here I would like to contrast their views on the nature of economic progress and the significance of cities in that progress. Some interesting parallels There are some interesting parallels between George and Jacobs. Both were public intellectuals who rebelled against mainstream economic thinking — for George it was classical economics, for Jacobs neoclassical economics. Both had a firm grasp of how markets work, were critical of crony capitalism, and concerned with the problems of “the common man.” And both established their reputations outside of academia. George was a strong advocate for free trade and an opponent of protectionism. He also understood Adam Smith’s explanation of the invisible hand. As George writes in […]

Over at Greater Greater Washington, Ms. Cheryl Cort attempts to temper expectations of what she calls the “libertarian view (a more right-leaning view in our region)” on affordable housing. It is certainly reassuring to see the cosmopolitan left and the pro-market right begin to warm to the benefits of liberalization of land-use. Land-use is one area the “right,” in it’s fear of change, has failed to embrace a widespread pro-market stance. Meanwhile, many urban-dwellers who consider themselves on the “left” unknowingly display an anti-outsider mentality typically attributed to the right’s stance on immigration. Unfortunately, in failing to grasp the enormity of the bipartisan-caused distortion of the housing market, Ms. Cort resigns to advocate solutions that fail to deliver widespread housing affordability. Yes, adding more housing must absolutely be a part of the strategy to make housing more affordable. And zoning changes to allow people to build taller and more usable space near transit, rent out carriage houses, and avoid expensive and often-unnecessary parking are all steps in the right direction. But some proponents go on to say relaxing zoning will solve the problem all on its own. It won’t. Well, if “relaxing” zoning is the solution at hand, she may be right – relaxing will only help a tad… While keenly aware of the high prices many are willing to pay, Cort does not seem to grasp the incredible degree to which development is inhibited by zoning. “Relaxing” won’t do the trick in a city where prices are high enough to justify skyscrapers with four to ten times the density currently allowed. When considering a supply cap that only allows a fraction of what the market demands, one can not reasonably conclude “Unlimited FAR” (building density) would merely result in a bit more development here and there. A radically liberalized land-use regime would […]

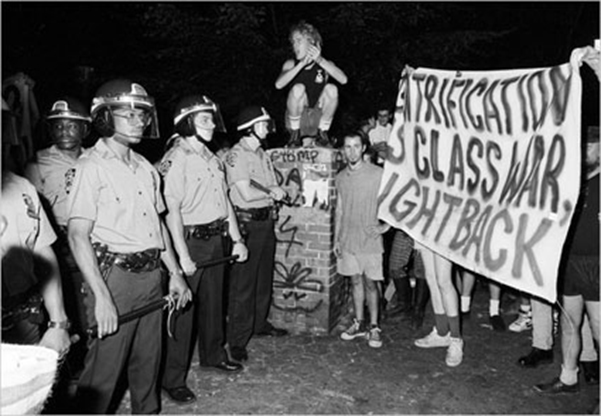

Gentrification is the result of powerful economic forces. Those who misunderstand the nature of the economic forces at play, risk misdirecting those forces. Misdirection can exasperate city-wide displacement. Before discussing solutions to fighting gentrification, it is important to accept that gentrification is one symptom of a larger problem. Anti-capitalists often portray gentrification as class war. Often, they paint the archetypal greedy developer as the culprit. As asserted in jacobin magazine: Gentrification has always been a top-down affair, not a spontaneous hipster influx, orchestrated by the real estate developers and investors who pull the strings of city policy, with individual home-buyers deployed in mopping up operations. Is Gentrification a Class War? In a way, yes. But the typical class analysis mistakes the symptom for the cause. The finger gets pointed at the wrong rich people. There is no grand conspiracy concocted by real estate developers, though it’s not surprising it seems that way. Real estate developers would be happy to build in already expensive neighborhoods. Here, demand is stable and predictable. They don’t for a simple reason: they are not allowed to. Take Chicago’s Lincoln Park for example. Daniel Hertz points out that the number of housing units in Lincoln Park actually decreased 4.1% since 2000. The neighborhood hasn’t allowed a single unit of affordable housing to be developed in 35 years. The affluent residents of Lincoln Park like their neighborhood the way it is, and have the political clout to keep it that way. Given that development projects are blocked in upper class neighborhoods, developers seek out alternatives. Here’s where “pulling the strings” is a viable strategy for developers. Politicians are far more willing to upzone working class neighborhoods. These communities are far less influential and have far fewer resources with which to fight back. Rich, entitled, white areas get down-zoned. Less-affluent, disempowered, minority […]

In a recent post, commenter Jeremy H. helped point out that the use of the term “public good” is grossly abused in the case of transportation. Even Nobel economists refer to roads as “important examples of production of public goods,” ( Samuelson and Nordhaus 1985: 48-49). I’d like to spend a little more time dispensing of this myth, or as I label it, an “Urban[ism] Legend.” As Tyler Cowen wrote the entry on Public Goods at The Concise Library of Economics: Public goods have two distinct aspects: nonexcludability and nonrivalrous consumption. “Nonexcludability” means that the cost of keeping nonpayers from enjoying the benefits of the good or service is prohibitive. And nonrivalrous consumption means that one consumer’s use does not inhibit the consumption by others. A clear example being that when I look at a star, it doesn’t prevent others from seeing the same star. Back when I took Microeconomics at a respectable university in preparation for grad school, I was taught that in some cases roads are public goods. We used Greg Mankiw’s book, “Principles of Economics” which states the following on page 234: If a road is not congested, then one person’s use does not effect anyone else. In this case, use is not rival in consumption, and the road is a public good. Yet if a road is congested, then use of that road yields a negative externality. When one person drives on the road, it becomes more crowded, and other people must drive more slowly. In this case, the road is a common resource. This explanation made sense, but I was skeptical – something didn’t sit right with me. Let’s take a closer look. First, Mankiw uses his assertion as an example of rivalrous vs nonrivalrous consumption, while not addressing the question of excludability. Roads are easily excludable through gates […]

Back a couple years ago, I noted an Econtalk podcast with Russell Roberts and Duke University Professor Mike Munger on the private bus system in Santiago, Chile. This week’s episode starts with Munger’s update on the Santiago transportation system after visiting for three weeks and spending a lot of time traveling the city’s buses and transit. This discussion comes at a perfect time to follow-up on Stephen Smith’s post on private busing in New York. Munger and Roberts discussed the advantages and problems of the evolution of the system over the years. In the case of the private system with over 3,000 competing private bus companies, accidents and injuries were common, and pollution was problematic. However, the regulation and publicization of the buses led to unintended consequences that were probably far worse than the drawbacks of the private system. Unfortunately, although the administration has apologized for the failures of the system, it would be politically impossible to revert to some of the beneficial aspects of the private system.

In an act of pure legislative idiocy in the face of overwhelming consensus among economists against rent control, the New York State Assembly started the ball rolling to strengthen rent regulation. NY Times: The Democratic-led Assembly passed a broad package of legislation designed to restrain increases on rent-regulated apartments statewide. The legislation would essentially return to regulation tens of thousands of units that were converted to market rate in recent years. In addition, the legislation would reduce to 10 percent, from 20 percent, the amount that a landlord can increase the rent after an apartment becomes vacant; limit the owner’s ability to recover a rent-regulated apartment for personal use; and increase fines for landlords who are found to have harassed their tenants as a way of evicting them. The legislation would also repeal the Urstadt Laws’ provision that in 1971 effectively took away most of New York City’s authority to regulate rents and transferred it to the state. Opponents of the legislation are concerned that the New York City Council, known for its pro-tenant leanings, would enact laws that are unfavorable to landlords. Expect some amazingly ignorant quotes from legislators while this is debated: Linda B. Rosenthal, an assemblywoman who represents the Upper West Side, said that unless rent-regulation laws were changed, middle class people were at risk of being driven out of the city. Actually, rent control drives out the middle class, making housing only affordable to the rich and beneficiaries of subsidies and rent controls. New housing will be nearly impossible for middle class tenants to find. Plus, for those who favor one particular class of people over others, rent control increases class tensions… “Pretty soon we’re going to end up with a city of the very poor and the very rich,” Ms. Rosenthal said. “Our social fabric […]

Recently, I came accross an article by Charles Johnson, who blogs at Rad Geek. The article had linked to a Market Urbanism post about how user fees and gas taxes fall well short of funding road use in the US. Charles’ article further debunks the Urbanism Legend asserted by free-market imposters that a free-market highway system would be similar to the system we see today. I like the post so much that I asked Charles about posting it at Market Urbanism. Charles requested that I, “indicate that the post is freely available for reprinting and derivative use under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 1.0 license.” I am happy to comply, and must admit that I haven’t taken the time to acquaint myself with Creative Commons. So, here it is, in it’s original form, and feel free to read the comments in the link: Yes, Virginia, government roads really are government subsidized, and no, they don’t approximate freed-market outcomes by Charles Johnson, RadGeek.com When left-libertarians argue with more conventionally pro-capitalist libertarians about economics, one of the issues that often comes up is government control over roads, and the ways in which state and federal government’s control over roads has acted as a large subsidy for economic centralization and national-scale production and distribution networks (and thus, to large-scale “big box” retailers, like Wal-Mart or Best Buy, dependent on the crafty arrangement of large-scale cross-country shipping as a basic part of their business model). People who have a problem with this analysis sometimes try to dispute it by arguing that government roads aren’t actually subsidized — that heavy users of government roads are actually getting something that roughly approximates a freed-market outcome, because users of government roads pay for the roads they get, in proportion to how heavily they use them, because government […]

Wow! This market is a mess. As a great follow up to his posts at CafeHayek on government’s intervention in the housing market, Russell Roberts discusses the situation and bailout with reason.tv: Also… Here’s the video from an Economics forum discussion at MIT (my Alma mater) on Wednesday: The US Financial Crisis What Happened? What’s Next? And another forum at USC. [HT Richard’s Real Estate and Urban Economics Blog]