Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

This piece was coauthored by Nolan Gray and Katarina Hall. It’s like Los Angeles, but worse. To many, that’s the mental image of Mexico City: a city of unending traffic, unbearable smog, and unrestrained horizontal expansion. Yet when one walks the streets of Mexico City, a distinct reality comes into view: a city of wide sidewalks and integrated bike lanes, lush parks and cool street tree canopies, and dense, mixed-use urban neighborhoods. As a matter of fact, nearly every neighborhood within Mexico City’s giant ring road—the Circuito Interior—has a walkscore above 95. Many major U.S. cities lack even one neighborhood with such a high score. Even on the outer fringe of Mexico’s sprawling Distrito Federal, neighborhoods often have walkscores upwards of 70, qualifying as “very walkable.” What makes Mexico City so walkable? The first thing an American might notice about Mexico City is just how busy the city’s sidewalks are. It’s a city of 21,339,781, and it shows. But this busyness isn’t a mere side-effect of size; it’s a natural result of the city’s generous sidewalks and high-quality pedestrian infrastructure. Many downtown roads host spacious sidewalks, accommodating an unending sidewalk ballet of commuters, tourists, and street vendors. Wide medians along major boulevards offer both refuge for crossing pedestrians and a public space in which people are encouraged to meet and relax. Many of the city’s busiest downtown areas have been closed to automobile traffic. Mexico City’s main road—Paseo de la Reforma—is reserved on Sundays for pedestrians and cyclists. “Jaywalking” is normal and in many cases is assisted by traffic police—a stark contrast to the near persecution pedestrians often face in U.S. cities. The ample space for pedestrians attracts not only foot traffic but also the people watchers who come to enjoy the vitality, in turn keeping many downtown […]

Co-authored by Tony Albert and Jeff Fong SF Curbed recently sat down with Patrick Burt, Mayor of Palo Alto, to get his response to the high profile resignation of Kate Vershov Downing. Downing, of course, was the Palo Alto Planning Commissioner who publicly announced that she will move her family from the city because of high housing prices. Mayor Burt’s response illustrates a complete failure to accept either the nature or the cause of our housing crisis. And were we not so desensitized to this type of thinking here in the Bay Area, it would be hard to distinguish his comments from satire. Too Many…Jobs? Mayor Burt’s first, and perhaps most bizarre, assertion is that Palo Alto’s problem is job growth—both within the city as well as within its Peninsula neighbors. And that part of the solution must be to slow down or displace new job creation. Take a minute and let that sink in. An elected government official is calling out job growth as a problem, and advocating for policies to slow it down. Mayor Burt says that… we’re in a region that’s had extremely high job growth at a rate that is just not sustainable if we’re going to keep [Palo Alto] similar to what it’s been historically. Of course we know that the community is going to evolve. But we don’t want it to be a radical departure. We don’t want to turn into Manhattan. Job growth increases housing demand, and if housing supply increases more slowly than housing demand, housing prices rise to make up the difference. Mayor Burt is willing to admit that housing prices are too high, but actively rejects the idea that Palo Alto needs to significantly intensify land use with town homes or multi-family apartments. This leaves him backed into the absurd corner of addressing […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Episode 1 of the Market Urbanism podcast came out this week. Nolan Gray plans to release new episodes bi-weekly. The RSS feed is http://feeds.soundcloud.com/users/soundcloud:users:236686274/sounds.rss You can currently find the podcast on Soundcloud and PlayerFM. It will be available within the next few days on iTunes, Stitcher, and TuneIn. If there are other podcasting services you would like me to plug the RSS feed into, please let me know in the comment section below. Cities And The Growth Of Our Collective Brain by Emily Hamilton Sandy Ikeda describes the entrepreneur’s environment as the “action space.” Today, an action space could be in a suburban home for an entrepreneur who creates a digital product that’s sold online. While action space doesn’t necessarily need to be a place of high density, this face-to-face element remains a key part of the world’s most productive action spaces. Economist Sandy Ikeda, a previous MU contributor, is back. Here’s the first of what will be weekly content, published every Tuesday at 10am eastern standard time–How The Housing Market Works In other words, it’s not the entrepreneurs, developers, architects, and construction companies that build very expensive housing in cities like New York that drives up housing prices! Indeed, those people are responding to what they believe buyers are willing to pay, and if they are prevented from building those units the result will be higher prices for everybody. And if you observe housing prices rise despite increasing supply, that probably indicates demand is currently increasing faster than supply. Prices, however, would have been even higher were the government to undertake policies that restricted supply. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer is spending his last night tomorrow in Austin. Then he’ll spend a couple days in San Antonio, before leaving Texas. His Forbes article this week […]

Phew! It’s finally here. After spending a good chunk of my summer researching podcasting, reaching out to potential guests, and recording my first few episodes, I am excited to announce the launch of the Market Urbanism Podcast. You can currently find the podcast on Soundcloud and PlayerFM. It will be available within the next few days on iTunes, Stitcher, and TuneIn. If there are other podcasting services you would like me to plug the RSS feed into, please let me know in the comment section below. Below, you can find a transcript. Given the amount of extra time it takes to transcribe the typical 30 minute episode, this probably won’t be a regular occurrence. That said, if anyone is interested in taking up this job, and getting some credit as an official member of the Market Urbanism Podcast team, message me on Twitter at @mnolangray. Stay tuned next week for a discussion with Emily Hamilton on the relationship between land-use regulation and housing affordability. Enjoy the show! Welcome to the Market Urbanism podcast, where we’re liberalizing cities from the bottom up. I’m your host Nolan Gray, a writer for Market Urbanism and a graduate student in urban planning. In this first episode I’d like to welcome you to the podcast by answering three questions you’re probably already asking yourself: First, what market urbanism? To give you the short answer, market urbanism is the synthesis of classical liberal thought with urban planning and policy. On the market side of the term, we place a lot of value on empowering individuals, recognizing the importance of economic liberty, and celebrating the complex spontaneous orders that organize human life. On the urbanism side of the term, to put it simply, we love cities. We’re interested in understanding what makes for bustling streets, healthy neighborhoods, and prosperous […]

[Editors note: Sandy Ikeda was an original Market Urbanism writer and is now a regular columnist for the Foundation for Economic Education, or FEE.org. FEE has offered republishing rights, so Sandy’s past work will be appearing here every Tuesday at 10am eastern time] People sometimes argue that we need substantial housing subsidies in some very expensive cities because “the cost of building new housing is greater than what most people can afford.” It’s certainly true that families earning low or moderate incomes have a hard time buying or renting brand-new housing. But that’s not only the case today; it’s been true throughout the history of civilization, from Uruk to New York. The ABCs of Housing The housing market is subject to the same forces of supply and demand as any other market, although of course there are things that distinguish it from, say, the market for fast-food. For instance, unlike a hamburger, a house is durable: it’s not consumed all at once. It also depreciates: the average house in the United States, for example, has a useful life of about forty to sixty years before major renovations become necessary. Let’s say there are 3 categories of housing – A, luxury housing; B, middle-income housing; and C, low-income housing – and that houses are continuously built, age, and wear down. In the real world there are of course many more than 3 categories but let’s assume for simplicity that there are only these three. Now, this is very much like the market for automobiles, which are also durable. In the new-car market you have at the high-end the Mercedes S-Class Sedan, while at the low-end the Ford Fiesta, and in the middle there’s the Honda Accord. And within each category there’s an array of prices depending on initial quality, age, and […]

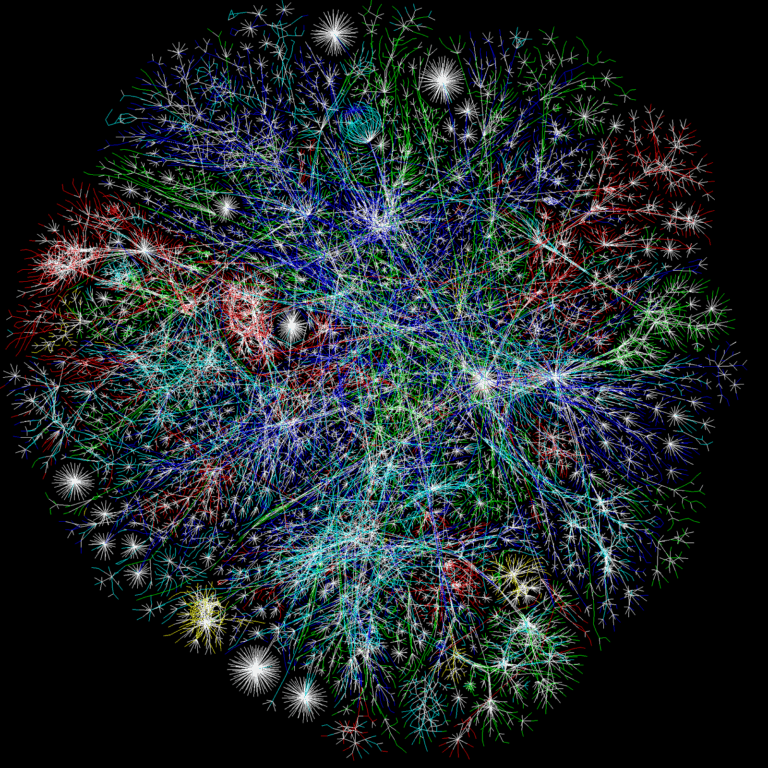

In his famous 2010 Ted Talk Matt Ridley points out that a growing human population has facilitated increasing standards of living because more people means a faster growth rate of innovation. He explains that humans’ propensity to exchange means that as a society we all benefit from each other’s ideas. No single person knows how to make a pencil from scratch, but we can all benefit from pencils (and much more complex tools) because collectively we have the knowledge to produce them. Ridley describes technological progress as a product of the collective brain — the space where our “ideas have sex.” Ideas “meet and mate” perhaps most obviously on the Internet, where the best encyclopedia in human history is crowd-sourced. This process is constant in the analog world also. The story of Microplane — a company that went from making printer parts, to woodworking tools, to kitchen gadgets and instruments for orthopedic surgeons — illustrates the innovations that come from ideas meeting and mating across entirely different industries. Cities provide the ideal location for these meetings because they bring together people from varied industries, backgrounds, and priorities. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs identifies four qualities that are necessary for diverse neighborhoods: At least two primary land uses; Small blocks; Buildings of diverse ages and types; and A high density of buildings and people. These characteristics facilitate an urban environment in which people of different professions, interests and income levels come into contact with one another as they go about their daily routines. In turn, this human contact puts people in an ideal position for innovation and entrepreneurship. Sandy Ikeda describes the entrepreneur’s environment as the “action space.” Today, an action space could be in a suburban home for an entrepreneur who creates a digital product that’s sold online. While […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Buses and Trains: The Turtle and the Hare? by Asher Meyers With buses a relatively safe, cheap and green form of travel, the wisdom of the government favoring trains at great public expense is dubious. This isn’t to say that trains are bad and buses are good—to each his own. But given the trade-offs involved, buses cannot be dismissed as inferior and obsolete—in the real world, budgets are limited and prices matter, so a small sacrifice of time and comfort is worth the savings. Parking Requirements Increase Traffic And Rents. Let’s Abolish Them. by Brent Gaisford Let’s get rid of parking minimums and allow new apartments to be built either without parking, or the reduced amount of parking preferred by developers. People without parking are less likely to drive, and less driving means less traffic. Plus, we’ll be one step closer to reducing our stratospheric rents. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer is in Austin. His two Forbes articles this week were about how Washington, DC’s Zoning Regulations Target ‘Fast Casual’ Restaurants and Tokyo’s Affordable Housing Strategy: Build, Build, Build The city had 142,417 housing starts in 2014, which was “more than the 83,657 housing permits issued in the state of California (population 38.7m), or the 137,010 houses started in the entire country of England (population 54.3m).” Compare this with the roughly 20,000 new residential units approved annually in New York City, the 23,500 units started in Los Angeles County, and the measly 5,000 homes constructed in 2015 throughout the entire Bay Area. Scott’s previous article on Austin’s rail transit, already well-cited by local media, got additional coverage in the American Spectator. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Adam Hengels on Stark Truth Radio with Robert Stark Ahmed Shaker posted videos of pedestrian and street traffic in […]

Everybody in LA can agree on one thing – traffic blows hard. Harder, even, than these guys: Hate traffic? Blame parking. But here’s a secret: people don’t cause traffic. Cars do. And you know what makes people use cars? Parking. If you’ve got nowhere to put your car when you arrive, you aren’t going to drive, and you aren’t going to contribute to traffic. Research has shown that for every 10% increase in parking, 7.7% more people commute with a car. Hate high rent? Blame parking. That’s a bad start. But it gets worse. Parking is also driving up your rent. Building parking spaces is incredibly expensive – each underground parking spot in LA costs about $35,000. Even if your unit includes “free” parking, you’re paying for the cost of that parking in your rent every month, whether you want to or not. Parking is cheaper to build above ground (if you can call $27,000 cheap), but then it takes up valuable space for apartments. All those dollar signs have an impact–UCLA professor Donald Shoup has calculated that requiring parking reduces the number of units in new apartment buildings by 13%. But parking is even more insidious than that. Often, when a new housing project is proposed, one of the first things that angry people (NIMBYs) yell about is traffic. Sometimes, those NIMBYs successfully stop housing from being built, and we desperately need all the housing we can get to contain our skyrocketing rents. Then why the hell do we require all new buildings to include so much parking? You’d think, then, that developers might stop providing parking. But they can’t, because we did something really, really dumb. We’ve created a system that requires parking to be provided with all new projects. For an apartment […]

In America, there is an almost stifling consensus among pro-urban types—trains are good, trains are right, trains work. Trains have marked the upward surge of mankind—trains clarify and capture the essence of the American spirit. “Just look at Europe!” Yes, let’s look at Europe. What you’ll find is a startling change—Europeans are embracing the conventional coach bus for trips once exclusively the province of trains and private automobiles. The Economist has called it a ‘Revolution on Wheels.’ The consultancy Oliver Wyman titled their report ‘Hit by a Bus: European Rail.’ Why did this happen? Trains were supposed to be the future, and buses a shoddy relic of the past. Up until a few years ago, it was illegal to run intercity buses in Germany and France, among others, to protect their state-owned train system from competition. When Germany relaxed this ban in early 2013, suddenly a host of newcomers sprang up to serve the demand for travel between cities. By year’s end, weekly bus journeys in Germany had increased by 230%. The industry went through a cycle of intense competition between several players, followed by consolidation into a few big rivals. Just this summer, the biggest player in Germany, Flixbus, acquired the continental operations of Megabus, a big player in the United States, as well as domestic operations by Germany’s Postbus. During the summer of 2015, France followed with its own deregulation to allow intercity buses. The Economist writes that “France had only 100,000 intercity coach passengers in all of 2014, but saw 250,000 in the single month from mid-August.” Italy, Sweden and Finland have also deregulated their markets in recent years. Buses have one premier appeal—they are cheap. For the 140-mile trip I took this weekend from Brussels to Cologne, tickets were $10, while a train ride was $44. Browsing […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism Does Home-sharing Create Negative Externalities? by Michael Lewyn Homeowners’ fear of being overrun by “transient” renters is based on an outmoded picture of urban life. In a rural area where most people are born and die in the same town, a fear of “transients” may make sense- but urban life is already highly transient. In renter-dominated blocks, people move in and out every year, so transience is already the norm. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer has, starting tomorrow, one week left in Austin. Tomorrow he’s visiting the southwestern Texas town of San Angelo. His two Forbes articles were about a Houston builder constructing the nation’s largest micro-unit project and Why Austin Needs to Unleash Sixth Street These noise complaints follow the same rationale as complaints now routinely made about new housing, offices or retail. That is, people move into urban areas thinking they will enjoy the benefits of greater density and culture; but when those qualities prove inconvenient, they try to squelch them. Scott’s work was also splashed all over Austin’s local news this week. He did two TV appearances–to discuss the city’s rail transit line and safety on sixth street–and was cited about these issues in the Austin American-Statesman, the Austin Business Journal, Curbed Austin and Austin.com (among other publications). 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Ahmed Shaker reports his experiences of Chuadanga, Bangladesh and finds it dense, bustling, full of mixed-uses, and private transportation options are plentiful. Shanu Athiparambath wrote Why Do People Love Their Cities But Hate Urban Living? Todd Litman wrote: Funding Multi-Modalism at Planetizen via Rocco Fama and Christopher Robotham: Donald Shoup and Aaron Renn on the City Journal podcast via Mark Frazier: Does Elon Musk Understand Urban Geometry? via Matt Robare: City taxes as urban growth policies: choosing the taxes that get you […]