Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

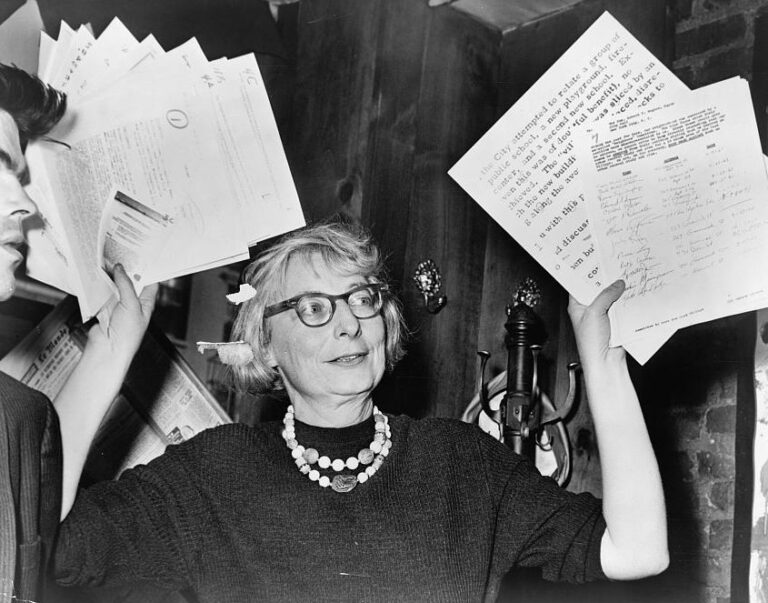

My guest this week is Sanford Ikeda, a professor of economics at SUNY Purchase and a visiting scholar at New York University. He has written extensively on urban economics, policy, and planning. Professor Ikeda introduced me to urban economics and urban planning when he gave a presentation on Jane Jacobs at a FEE summer seminar that I attended back in 2012. Here are a few of the topics we discussed in the episode: If you haven’t already, I highly suggest reading Jane Jacobs. The natural place to start is The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Her other books, including The Economy of Cities and Systems of Survival, explore topics ranging from economics to political philosophy. Professor Ikeda has written extensively on Jane Jacobs. You can read a nice overview here. If you would like to read more, click here for a paper he wrote on F.A. Hayek, Jane Jacobs, and the importance of local knowledge in cities. He is also a regular contributor to Freeman and Market Urbanism. We also discussed William H. Whyte’s famous documentary on public space, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. It’s well worth checking out. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

This week’s column is drawn from a lecture I gave at the University of Southern California on the occasion of the retirement of urban economist Peter Gordon. One of my heroes is the urbanist Jane Jacobs, who taught me to appreciate the importance for entrepreneurial development of how public spaces—places where you expect to encounter strangers—are designed. And I learned from her that the more precise and comprehensive your image of a city is, the less likely that the place you’re imagining really is a city. Jacobs grasped as well as any Austrian economist that complex social orders such as cities aren’t deliberately created and that they can’t be. They arise largely unplanned from the interaction of many people and many minds. In much the same way that Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek understood the limits of government planning and design in the macroeconomy, Jacobs understood the limits of government planning and the design of public spaces for a living city, and that if governments ignore those limits, bad consequences will follow. Planning as taxidermy Austrians use the term “spontaneous order” to describe the complex patterns of social interaction that arise unplanned when many minds interact. Examples of spontaneous order include markets, money, language, culture, and living cities great and small. In her The Economy of Cities, Jacobs defines a living city as “a settlement that generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Living cities are hotbeds of creativity and they drive economic development. There is a phrase she uses in her great work, The Life and Death of Great American Cities, that captures her attitude: “A city cannot be a work of art.” As she goes on to explain: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works […]

If you regularly read about cities, you might notice that Texas cities rarely seem to come up. We make cases for why Detroit is definitely coming back—just you wait! We come up with elaborate theories of how cities can become the next Silicon Valley. We spend hours coming up with a solution to New York City’s costumed panhandler problem. Yet the four urban behemoths of the Lone Star State—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin—remain conspicuously absent from the conversation. Boy, has that changed. Earlier this year I wrote a sprawling defense of Houston. Scott Beyer spent the summer writing a series of articles for Forbes profiling the cool things happening in cities across the state. John Ricco recently launched the “Densifying Houston” Twitter feed and discussed the phenomenon on Greater Greater Washington. Just this past weekend, City Journal released an entire special issue dedicated to Texas. Through all this, many have been surprised to learn that a city like Houston could serve as a model for land-use policy and economic growth for struggling coastal cities. Yet two criticisms regularly seem to come up, at least related to Houston: “Houston is an unplanned hell-hole! It’s proof that land-use liberalization would be a disaster.” “Houston isn’t unplanned! It’s as heavily planned as any other city, just look at the covenants.” Since there seems to be a lot of confusion about land-use regulation and planning in Houston, here’s a quick explainer on what Houston does regulate, doesn’t regulate, and how private covenants shape the city. 1. What Houston Doesn’t Do Houston doesn’t mandate single-use zoning. Unlike every other major U.S. city, Houston doesn’t mandate the separation of residential, commercial, and industrial developments. This means that restaurants, homes, warehouses, and offices are free to mix as the market allows. As many have pointed out, however, market-driven separation of incompatible uses—think […]

1. This week at Market Urbanism: The “Global Buyers” Argument by Michael Lewyn The argument makes sense only when you add the following premise: housing prices can only be high in the presence of huge numbers of rich foreigners. I really don’t see any reason to take this premise seriously. Home-Sharing and Housing Supply by Michael Lewyn And if turning long-term rentals into short-term rentals is socially harmful, isn’t it even more harmful to prevent those long-term rentals from being built in the first place? Yet government does exactly that through zoning codes- often at the behest of neighborhood homeowners. Visions of Progress: Henry George vs. Jane Jacobs by Sandy Ikeda Much has been written, pro and con, on George’s single tax and also on Jacobs’s battles with planners the likes of Robert Moses, and if you’re interested in those issues you can start with the links provided in this article. Here I would like to contrast their views on the nature of economic progress and the significance of cities in that progress. Urban[ism] Legend: A Home Is A Good Investment by Emily Hamilton pursuing policies that encourage homeownership at the expense of other investment vehicles leaves people of all income levels worse off. Often, home ownership simply leads to higher levels of housing consumption rather than wealth-building. The consequences of buying a home may be dire for low-income families, and for the middle-class the decision should be based on rational calculations rather than the homeownership cheerleading that both parties offer. Airbnb Crowding Out Is A Symptom, Not A Cause Of Housing Shortages by Jim Pagels That Airbnbs may in fact take some small portion** of houses from the optionally relatively fixed full-time housing stock is a symptom, not a cause, of housing shortages and high prices. Asking if […]

When journalists, NIMBYs, politicians, and activists make claims about Airbnb taking potential full-time housing stock and converting it to leisure space, they operate under the assumption that the housing supply must be fixed. This assumption is half true: By no means must the housing supply be fixed, just as the supply of laptops, shoes, or milk has no requirement to be fixed. In reality, though, the supply is, yes, somewhat fixed, but that is merely an option, chosen by NIMBY residents, politicians, and misguided housing activists* that force through restrictive construction policies that either largely inhibit or outright prohibit new housing development. Economists Ed Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks estimate that what they call the “zoning tax” accounts for, on average, more than 10 percent of the price of the average U.S. home. In cities with extreme restrictions like San Francisco, the zoning tax is as high as 50%! Here’s a thought exercise: Imagine the U.S. had very restrictive laws regarding smartphone production. If a new Apple factory wanted to produce more iPhones, each phone would have to go through a long, onerous, and costly approval process by the local government and regulatory agencies. In addition, nearby established phone factories or incumbent phone owners in many areas could successfully pressure the local government to prohibit the new factory from producing phones. Because of these burdens, the supply of phones rises only very slowly (far less than the growth in phone demand), and many people have to go about sharing a phone with family or friends or diverting huge portions of their monthly budget to owning/renting a scarce phone. In this alternative phone regulation reality, the criticism that “some tiny portion of phones are used for leisure like social media and games rather than important things like work or talking to […]

Despite its poor track record, homeownership is the bad investment idea that never seems to die. Even though the financial crisis revealed the risks that homeowners take on by making highly leveraged purchases, policymakers are still developing new programs to encourage home buying. Both the Clinton and Trump campaigns are continuing the political support for homeownership that dates back to the Progressive Era. Since the New Deal, homeownership has been touted as a tool to reduce poverty and as a route to wealth-building for the middle class. Even before the subprime-lending crisis revealed the risk that low-income borrowers took on with homeownership, researchers have explained the problems with using homeownership programs as a poverty reduction tool. Joe Cortright recently pointed out that homeownership is a particularly risky bet for low-income people who may only have access to credit during housing market upswings, leaving them more likely to buy high and sell low. Even for middle- and high-income households, homeownership is a weak investment strategy. Politicians across the political spectrum tout homeownership as key to a middle-class existence, but homeownership will make many buyers poorer in the long run compared to renting. The real estate and mortgage industries have popularized the claim that “renting is throwing your money away,” but owning a home comes with a steep opportunity cost. Renters can invest the money that they would have spent on a down payment in more lucrative stocks, and they don’t take on the risk of home maintenance. The New York Times created a popular calculator designed to determine whether renting or owning makes better financial sense. The calculator’s defaults assumptions are overly optimistic in favor of homeownership as the better strategy for most households. They include a 1% rate of house price increases after accounting for inflation, but the historical average is just 0.2%. Similarly, the calculator defaults to a […]

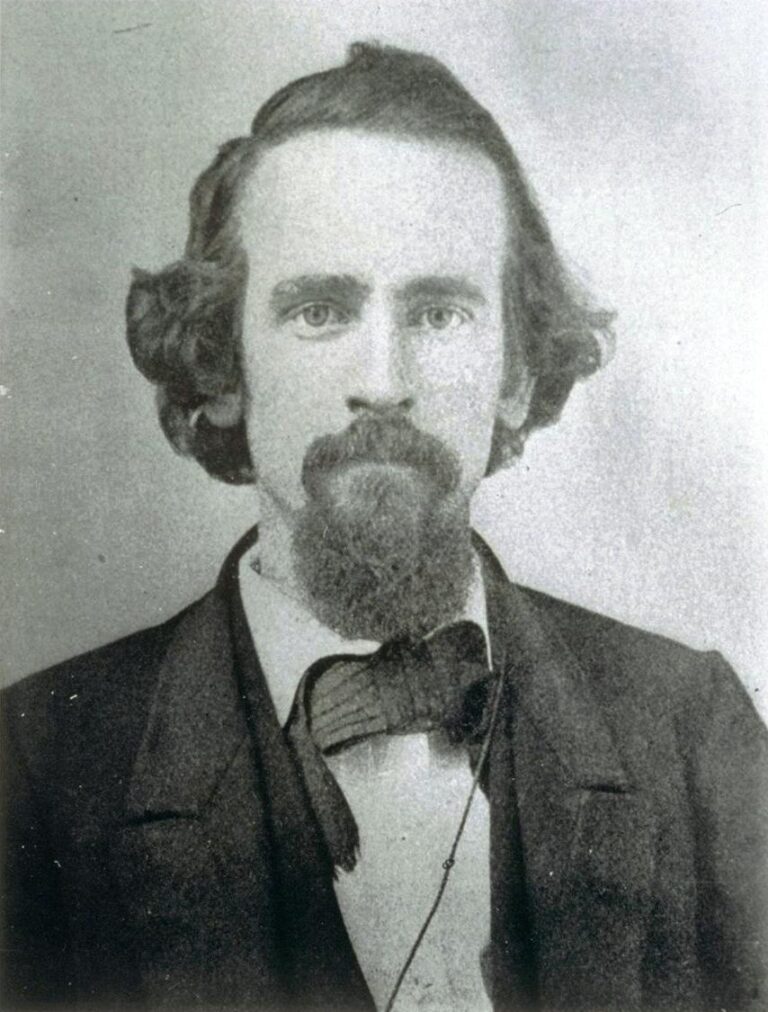

Henry George and Jane Jacobs each have an enthusiastic following today, including, I’m sure, some readers of The Freeman. For those who might not know, Henry George is the late-19th-century American intellectual best known for his proposal of a “single tax” from which he believed the government could finance all its projects. He advocated eliminating all taxes except that on the rent of the unimproved portion of land. He viewed that rent as unjust and solely the result of general economic progress unrelated to the actions of landowners. Jane Jacobs, writing about one hundred years later, is an American intellectual best known for her harsh and incisive criticism of the heavy-handed urban planning of her day. She advised ambitious urban planners to first understand the microfoundations of urban processes — street life, social networks, entrepreneurship — before trying to impose their visions of an ideal city. Much has been written, pro and con, on George’s single tax and also on Jacobs’s battles with planners the likes of Robert Moses, and if you’re interested in those issues you can start with the links provided in this article. Here I would like to contrast their views on the nature of economic progress and the significance of cities in that progress. Some interesting parallels There are some interesting parallels between George and Jacobs. Both were public intellectuals who rebelled against mainstream economic thinking — for George it was classical economics, for Jacobs neoclassical economics. Both had a firm grasp of how markets work, were critical of crony capitalism, and concerned with the problems of “the common man.” And both established their reputations outside of academia. George was a strong advocate for free trade and an opponent of protectionism. He also understood Adam Smith’s explanation of the invisible hand. As George writes in […]

One common argument against Airbnb and other home-sharing companies is that they reduce housing supply by taking housing units off the long-term market.* As I have written elsewhere, I don’t think home-sharing affects housing supply enough to matter. But even leaving aside the empirical question of whether this will always be true, there’s a theoretical problem with the argument that if someone fails to use their land for long-term rental housing, government must step in. It seems to me that this argument, if applied with even a minimal degree of consistency, leads to absurd results. For example, suppose that Grandma has a spare room in her house, and instead of renting it on Airbnb she allows the room to be unused. Should Grandma be forced to rent out the room? Of course not. A home-sharing critic might argue that an unused room is different from a room that is likely to be rented out to a long-term tenant. Indeed it is- but in fact, Grandma’s failure to rent the room to anyone is more socially harmful than her renting the room on Airbnb. In the latter situation, a traveler benefits (from a cheaper rate than a hotel, or at least for a different kind of experience) and Grandma benefits by getting money from the traveler. By contrast, in the former situation, no one benefits. It could be argued that Grandma’s rights should be unimpeded, but that regulation should be targeted towards the amateur hotelier who seeks to rent out an entire building all-year round, rather than using the building for more traditional tenants. Even here, the argument based on housing scarcity leads to absurd results. Suppose the evil landlord Snidely Whiplash decides, instead of renting out his building on Airbnb, to use the building for a vacation house one day a year […]

One common argument against building new market-rate housing is that there is an infinite supply of rich foreigners willing to soak up new supply. One obvious flaw in this argument is that housing prices do occasionally go down even in expensive places. But even leaving aside this reality, the “foreign buyers” argument is not logically provable, since there is no way of knowing whether there are more rich foreign buyers in San Francisco than in, say, Raleigh or Houston. Thus, the argument rests on the following chain of logic: 1) we know that there are rich foreigners taking over Expensive City X (but not Cheap City Y) because housing prices are high; (2) therefore, the rich foreigners are what keep housing prices high in City X. The argument makes sense only when you add the following premise: housing prices can only be high in the presence of huge numbers of rich foreigners. I really don’t see any reason to take this premise seriously.

1. This week at Market Urbanism Shut Out: How Land-Use Regulations Hurt the Poor by Sandy Ikeda My colleague Emily Washington and I are reviewing the literature on how land-use regulations disproportionately raise the cost of real estate for the poor. I’d like to share a few of our findings with you. Are States Really The Solution To Urban Mismanagement? by Matt Robare Cities would finally have to confront their land use and economic development policies, employee compensation and infrastructure management; while states would have to confront their redistribution of revenue to rural areas. While state emergency managers and receivers have turned financially struggling cities around, it’s not hard to think that they might be needed less if cities were free. Market Urbanism Podcast Episode 02: Emily Hamilton on Land-Use Regulation and the Cost of Housing by Nolan Gray The question I am left pondering: how can we convince homeowners—who have a large vested interest in the current system—to support land-use liberalization? Feel free to share your thoughts on this and other topics in today’s episode in the comment section below or with Emily and I on Twitter. Supply and Demand: A Response to 48hills by Jeff Fong No matter what example we look at or how we cut up the data, there’s nothing out there to contradict the basic YIMBY story about supply, demand, and price. Unless, of course, you don’t actually understand the story, which may be the problem in Ms. Bronstein’s case. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer left Texas this week for Phoenix, stop #8 on his 30-city writing tour. He has settled in the neighboring suburb of Tempe, which is home to Arizona State University and is perhaps the metro’s most intensive urban area. Scott also started a Twitter account this week, and will post […]