Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

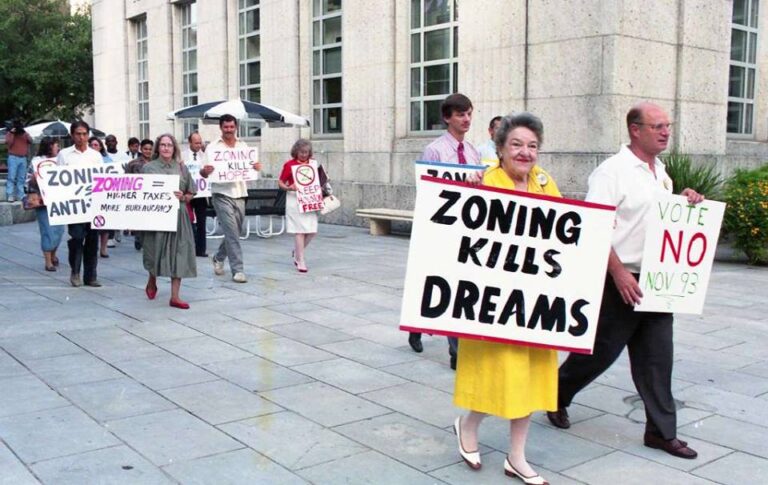

1. This week at Market Urbansim: America’s Progressive Developers–The Uptown Gateway Council by Scott Beyer San Diego, too, may be subject to this downzoning trend. Like California’s other destination cities, San Diego has both a fast-growing population, and restrictive land-use regulations that keep housing supply from meeting demand. But rather than reforming their laws in a progressive direction, they’re doing the opposite. The Psychological Consequences Of Rent Control by Sandy Ikeda Fewer cities today practice the sort of rent control Hayek wrote about in the mid-twentieth century. But government meddling in housing continues in the United States and elsewhere. America’s political leaders are fond of proclaiming a citizen’s “right to housing,” the manifestations of which have been Fannie Mae, politically driven subprime lending, and (at times) expansionary Federal Reserve policy. The macroeconomic results have been obvious and disastrous. But let’s not forget Hayek’s “micro-social” consequences. 2. MU Elsewhere On November 29, Emily Hamilton will debate urban housing issues with Randal O’Toole of the Cato Institute and Gerrit Knaap of the National Center for Smart Growth in Washington, DC (event details) 3. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer completed his first full week in Los Angeles. He will spend Thanksgiving weekend studying in nearby Riverside, one of California’s fastest growing metros. Much of the growth within this Inland Empire region results from poorer people getting priced out of L.A. and San Diego. 4. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Lyman Stone wrote “Appalachia is Dying. Pikeville is Not. Deep in Kentucky’s Appalachian Mountains, a Small City Finds Success“ Michael Lewyn wants a YIMBY conference in NYC Tobias Cassandra Holbrook is curious about the impact of charter schools on urbanism via Asher Meyers, “A leading light of market urbanism? Herman Mashaba – the new mayor of Johannnesburg.” via Chris Kaz Wojtewicz, Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic […]

The University of Chicago Press has published a “definitive” edition of F. A. Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty under the editorial guidance of long-time Hayek scholar Ronald Hamowy. Given my interest in urban issues, it’s a good time for me to focus on chapter 22, “Housing and Town Planning.” It has several insights that I really like, but given the constraints of this column, for now I’ll talk about Hayek’s take on rent control. I must confess that it was several years after I became interested in the nature and significance of cities that I learned that Hayek had written anything on what we in the United States call “urban planning.” (Well, that’s not quite true; I did read The Constitution of Liberty as a graduate student, but in those days I didn’t appreciate how important cities are to both economic and intellectual development, so it evidently made no impression on me.) The analysis has a characteristically “Hayekian” flavor to it, by which I mean he goes beyond purely economic analysis and points out the psychological and sociological impact of certain urban policies that reinforce the dynamics of interventionism. The Economics of Rent Control Hayek’s economic analysis of rent control sounds familiar to modern students of political economy perhaps because it’s so widely (though not universally) accepted. This was hardly the case in 1960, when his book was first published. Hayek points out that despite the good intentions of those who support it, “any fixing of rents below the market price inevitably perpetuates the housing shortage.” That’s because at the artificially low rents the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. One effect of the chronic housing shortage that rent control produces is a drop in the rate at which apartments and flats would normally turn over. Instead, rent-controlled housing becomes […]

1. This week at Market Urbansim: Preservation At The Expense Of Liberty by Sandy Ikeda Using political power to preserve any cherished way of life — trying to stay the uncertain dynamic that washes through social institutions, norms, and conventions — is not only futile but ultimately destructive of liberty. That goes for preserving a historic community as much as preserving current marriage practices; keeping the natural environment pristine as much as maintaining age-old religious practices; or freezing a particular income distribution as much as insisting on keeping certain “undesirables” outside our borders. 2. Where’s Scott? After flying back from San Antonio, where he gave a speech, Scott Beyer relocated to Glendale, a nearby suburb of Los Angeles. This morning he was the feature cover story (paywall) for the San Antonio Business Journal, which described his cross-country trip and upcoming economic report on the city. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Emily Hamilton published an op-ed about her new Mercatus research on smart cities, privacy, and transparency. “Not all smart city innovations are so benign. City governments increasingly have the ability to collect and use their residents’ data.” Bjorn Swenson asks “what’s the Market Urbanism strategy going to be under the Trump administration?” Bjorn Swenson writes a post reflecting on the election considering the disconnection of transportation between the rust belt and coastal areas Michael Hamilton spotted a California NIMBY billboard in his feed Ahmed Shaker asks, “Is what he (Robin Hanson) says about high-rises being less expensive to construct true?”: Why Aren’t Cities Taller? via Rocco Fama: Does New York need another Robert Moses? via Adam Hengels: While You Weren’t Looking, Donald Trump Released a Plan to Privatize America’s Roads and Bridges via John Morris: The Ghost Tenants of New York City “People underestimate the role informal, “black markets” play in providing housing in severe shortage areas.” […]

“Everything passes. Nobody gets anything for keeps. And that’s how we’ve got to live.” –Haruki Murakami I feel lucky to live in Brooklyn Heights. It’s been called New York City’s first suburb. It offers easy access to most parts of Manhattan, thanks to the convergence of several important subway lines, and the view of Lower Manhattan from here is one of the most spectacular in the City. Not surprisingly it’s one of the most desirable and expensive neighborhoods to live in. Along its periphery, warehouses and office buildings are constantly being converted into residences, to go along with townhouses in the neighborhood proper that were built in the early 1800s, as developers try to keep up with a demand that has remained strong even in a slack housing market. In my opinion the Brooklyn Heights district is one of the most charming, and probably the prettiest, in all of New York. So what’s to complain about? Urban Renewal and Landmarks Preservation Three things. First, in 1939 the area just east of the neighborhood underwent the largest urban renewal project of its time, razing 125 buildings over 21 acres and creating “Cadman Plaza,” the first of many so-called “super-blocks” built in major cities across the United States in the mid-twentieth century. Later, between 1947 and 1954, local authorities constructed the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) along the northern and western borders. Then in 1965 Mayor Wagner signed a law that made Brooklyn Heights the City’s first historic district (there are currently 100 such districts in New York) and eventually gave rise to the important Landmarks Preservation Commission. Cadman Plaza and the BQE effectively cut the Heights off from the hurly-burly of commercial development in neighboring districts. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has made it very hard and very costly to change the existing […]

1. This week at Market Urbansim: Collective Action Problems Are Similar For Land Use And Schools by Michael Lewyn …it occurred to me that there are some similarities between American school systems and American land use regulation. In both situations, localism creates gaps between what is rational for an individual suburb or neighborhood and what is rational for a region as a whole. The Great Mind And Vision Of Jane Jacobs by Sandy Ikeda As an economist working in the tradition of Mises, Hayek, and Kirzner, what have I learned from Jane Jacobs? In short: Densely populated settlements that embody a wide diversity of both skills and tastes are the incubators of dynamic social development and entrepreneurial discovery—Density + Diversity Development and Discovery—and that government intervention tends to undermine the free air of cities in which even ordinary people can do extraordinary things. Kotkin And The Atlantic- Spreading ‘Localism’ Nonsense Together by Michael Lewyn This is as true in California as it is anyplace else; when Gov. Brown tried to make it easier for developers to bypass local zoning so they can build new housing, the state legislature squashed him. Local zoning has become more restrictive over time, not less. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer completed his San Diego stay, and is heading today into the Mexican border city of Tijuana, before moving to Los Angeles. He wrote 4 articles this week: San Antonio’s Growth Part of a Macro-Level U.S. Trend for The Bexar Witness & When Texas Stopped Looking and Feeling Like Mexico for Governing Magazine & Here’s Why Your Home Is 24% Overpriced & Philadelphia’s SEPTA Transit Workers Go On Strike…Again for Forbes. There is an entire eco-system of private transit options, big and small, that exist in most cities, including Philly. Many of them have already released formal game plans for this strike, showing the […]

The Atlantic Magazine’s Citylab web page ran an interview with Joel Kotkin today. Kotkin seems to think we need more of something called “localism”, stating: “Growth of state control has become pretty extreme in California, and I think we’re going to see more of that in the country in general, where you have housing decisions that should be made at local level being made by the state and the federal level too. You have general erosion of local control.” In fact, land use decisions are generally made by local governments–which is why it is so hard to get new housing built. This is as true in California as it is anyplace else; when Gov. Brown tried to make it easier for developers to bypass local zoning so they can build new housing, the state legislature squashed him. Local zoning has become more restrictive over time, not less. And the fact that state government has added additional layers of regulation doesn’t change that reality. But did the Atlantic note this divergence from factual reality, or even ask him a follow-up question? No, sir. Shame on them!

Jane Jacobs (May 4, 1916 – April 25, 2006), one of the most important and influential public intellectuals of the twentieth century, died a few days shy of her ninetieth birthday. The intellectual legacy she left for social theorists is as significant as that of anyone else of her generation. She was the author of nine books, including The Economy of Cities (1969), Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1984), The Nature of Economies (2000), and her most famous work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). She also published an article in the prestigious American Economic Review (“Strategies for Helping Cities,” September 1969). Most are surprised to learn that she held only a high-school diploma and began her book-writing well past the age of 40. In her first book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs argued that the urban planners of her day, infected by the top-down collectivist ideology that was the conventional wisdom among nearly all intellectuals, ignored the perspective of ordinary people on the street. Her position, radical for its time, was that real cities don’t conform to one person’s or group’s aesthetic ideal because visual order is not the same as actual social order. She argued that complex social orders, such as a city, begin with ordinary people forming informal relations with one another in the neighborhoods in which they live, play, or work. Such networks emerge and thrive when people are able to have free and casual contact with acquaintances and strangers alike in the safety of streets, sidewalks, and other public spaces. But most of that safety is achieved not by aggressive formal policing but by voluntary recognition and informal enforcement of local norms. The key is for each neighborhood or city district to have sufficiently diverse attractions at […]

I just read a law review article complaining that some white areas in integrated southern counties were trying to secede from integrated school systems (thus ensuring that the countywide systems become almost all-black while the seceding areas get to have white schools), and it occurred to me that there are some similarities between American school systems and American land use regulation. In both situations, localism creates gaps between what is rational for an individual suburb or neighborhood and what is rational for a region as a whole. In particular, it is rational for each suburb to have high home prices (because that means a bigger tax base)- but I don’t think San Francisco-size rents and home prices are rational for a region as a whole. Similarly, it is rational for each individual neighborhood within a city to have restrictive regulations, because if one neighborhood is less restrictive it suffers from whatever burdens might result from new housing, without the broader benefit of lower citywide housing costs. How are school districts similar? Since the prestige of a neighborhood is related to its school district, and the prestige of school districts depends on their socio-economic makeup, it is rational for each suburb (or city neighborhood) to be part of a school district dominated by white children from affluent families, rather than to be part of a socially and racially diverse district. But if every middle-class or affluent area draws school district lines in a way that excludes lower-income children, the poor people are all concentrated in a few poor school districts (such as urban school districts in Detroit and Cleveland). Is this rational for the region as a whole? I suspect not.

1. This week at Market Urbansim: ‘Who better to determine local needs than property owners and concerned citizens themselves?’ by Michael Hamilton Instead, land-use regulations can, and often are, used as cudgels against disfavored groups or individuals. Issues of personal taste—yard size, material choices, building design, amount of parking—can be weaponized when turned into regulatory requirements and greatly decrease a plot of land’s value. Donald Shoup Takes San Francisco by Sandy ikeda As I said before, to do market pricing correctly, well, you need markets. What the San Francisco approach does is to try to mimic what it is thought a private market would do. But the standard of “at least one empty parking spot” is arbitrary – like mandating that every ice-cream cone have two and only two scoops of ice cream. The Shoup-inspired San Francisco solution is I think a step in the right direction, but only a step. Episode 05 of the Market Urbanism Podcast with Nolan Gray: Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring on Vital Little Plans This week on the Market Urbanism Podcast, I chat with Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring on the wonderful new volume Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs. From Jacobs’ McCarthy-era defense of unorthodox thinking to snippets of her unpublished history of humanity, the book is a must-read for fans of Jane Jacobs. In this podcast, we discuss some of the broader themes of Jacobs’ thinking America’s Progressive Developers–Silver Ventures by Scott Beyer Foremost among these is the Pearl Brewery, a 22-acre former industrial site that is north of downtown. “The Pearl” is now viewed by locals as San Antonio’s leading urbanist destination—as opposed to the touristy downtown—but it wasn’t always this way. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent week 4 in San Diego. His Forbes article was about […]

This week on the Market Urbanism Podcast, I chat with Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring on the wonderful new volume Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs. From Jacobs’ McCarthy-era defense of unorthodox thinking to snippets of her unpublished history of humanity, the book is a must-read for fans of Jane Jacobs. In this podcast, we discuss some of the broader themes of Jacobs’ thinking. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Pick up your copy of Vital Little Plans on Amazon. Mentioned in the podcast, Manuel DeLanda discusses Jane Jacobs in A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. Read more about the West Village Houses here. The question of Quebec separatism is a fascinating—and under-considered—element of Jacobs’ work. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.