Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

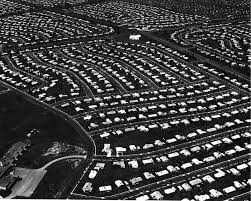

The economist F.A. Hayek explained why it’s impossible for human reason to successfully design complex systems such as markets or language. One can’t simply say, “Hey, I’d like to invent a Germanic language that does away with those troublesome genders and inflections but has plenty of Latin- and Greek-based words sprinkled in.” That would be English, of course, which evolved over centuries of trial and error. (Some might want to use Esperanto as a counterexample, but let’s face it: There are probably more people today who can speak Latin, a dead language, than can speak Esperanto.) The current fashion to construct mass-transit infrastructure in places, such as Phoenix, where none had existed before is like this in a certain sense. As Hayek explained, the problem is that reason, while powerful and creative, is imperfect and extremely limited compared to the complexity and open-endedness of the social world. As a result, all actions will have unintended consequences. The trick is to find “rules of the game” – such as private property and norms of reciprocity – that over time generate consequences that correct errors and promote rather than prevent social cooperation. While economists and social theorists since Adam Smith have understood this, many in the urban-planning profession don’t seem to have fully grasped the message. When Sprawl Was Good Since at least the 1970s in the United States the idea has been to try as much as possible to substitute mass-transit for the private car. To New Urbanists, for example, that is the key to solving a host of social ills including pollution, overcrowding, racial discrimination, oil-dependency, and alienation – all allegedly connected to the phenomenon of “sprawl.” (See, for example, the Charter of the New Urbanism.) I’ve been rereading Robert Bruegmann’s excellent book, Sprawl: A Compact History, in which he […]

Planners, like all professions, have their own useful mythologies. A popular one goes something like this: “Many years ago, us planners did naughty things. We pushed around the poor, demolished minority neighborhoods, and forced gentrification. But that’s all over today. Now we protect the disadvantaged against the vagaries of the unrestrained market.” The seasoned—which is to say, cynical—planner may knowingly roll her eyes at this story, but for the true believer, this story holds spiritual significance. By doing right today, the reasoning goes, planners are undoing the horrors of yesterday. This raises the question: are planners doing right today? That’s not at all clear. Just ask Hinga Mbogo. After emigrating from Kenya, Mr. Mbogo opened Hinga’s Automotive in East Dallas in 1986. Mr. Mbogo’s modest business is precisely the kind of thing cities need, providing a service for the community, taxes for the city, and blue-collar jobs. While perhaps not of the “creative class,” Mr. Mbogo and his small business represent the type of creative little plan that cities cultivate and depend on. Hinga’s Automotive has thrived for 19 years and looked primed for another 19. Unfortunately for Mr. Mbogo, Dallas planners had other plans. In 2005, the city rezoned the area to prohibit auto-related businesses. While rezonings—particularly upzonings—aren’t necessarily a bad thing, Dallas planners opted to force their vision through and implemented a controversial planning technique known as “amortization.” Normally when planners rezone an area, they allow existing uses that run afoul of the new code to continue operating indefinitely. These are known as “non-conforming uses” and they’re common in neighborhoods across the country, often taking the form of neighborhood groceries, restaurants, and small industrial shops. Yet under amortization, the government forces non-conforming uses to cease operating without any compensation. In the case of Hinga’s Automotive, this means […]

1. This week at Market Urbansim: China’s “Planned Capitalism” Kills Wealth by Sandy Ikeda China’s central planners haven’t even begun to appreciate, let alone practice, the lessons of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs, who viewed cities and the socioeconomic processes that go on in them as largely the result of spontaneous, unplanned entrepreneurial development. 2. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer is in Los Angeles, and this weekend will visit South Central neighborhoods like Compton, Watts and Huntington Park. His Forbes article this week is about how Los Angeles’ Pension Problem Is Sinking The City It has the nation’s largest homeless population, the worst traffic, and numerous other service failures. Lack of money isn’t the problem, since the city has both high taxes and a wealthy population. It is instead because large sums go to employee pension benefits. 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Roger Valdez wrote Gallup: Zoning Is Reducing American Productivity And Making The Poor Poorer Tobias Cassandra Holbrook asks about the potential impacts of property transfer tax. Jon Coppage wrote Whether Thriving or Failing, Cities Need Investment Nathan J. Yoder asks “What are good sources that compile information and long term comparative studies [about] what works best for housing for urban poor?” Isaac Mooers asks “imagine what Seattle would be like without FAR near our light rail stops.” via Krishan Madan, “A profile of the heroic Sonja Trauss and Laura Foote Clarke.“ via Michael Strong, Indy Johar recommends holding architects legally liable for their buildings as an alternative to urban planning via Will Muessig: Don’t Let Downtown Atlanta Become Privately Owned: Our Public Streets Must Remain Public via Krishan Madan: Zenefits’ Free Business Model Ruled Illegal In Washington State via Eric Fontaine: Four Million Commutes Reveal New U.S. ‘Megaregions’ via Kevin Watts, “NYT has an article on unsafe housing in Oakland, and […]

Sometimes, prosperity is an illusion. The massive building boom in the People’s Republic of China is creating outer signs of affluence, but there isn’t enough demand to put residents in the new homes. As in many similar urban projects across the country, the Chinese government has been pouring billions of dollars into Gansu Province to build a new city called Lanzhou New Area. The Washington Post reports, This city is supposed to be the “diamond” on China’s Silk Road Economic Belt — a new metropolis carved out of the mountains in the country’s arid northwest. But it is shaping up to be fool’s gold, a ghost city in the making. Lanzhou New Area, in Gansu province, embodies China’s twin dreams of catapulting its poorer western regions into the economic mainstream through an orgy of infrastructure spending and cementing its place at the heart of Asia through a revival of the ancient Silk Road. Hundreds of hills on the dry, sandy Loess Plateau were flattened by bulldozers to create the 315-square-mile city. But today, cranes stand idle in planned industrial parks while newly built residential blocks loom empty. Streets are mostly deserted. Life-size replicas of the Parthenon and the Sphinx sit surrounded by wasteland, monuments to profligacy. Spontaneous Cities China’s central planners haven’t even begun to appreciate, let alone practice, the lessons of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs, who viewed cities and the socioeconomic processes that go on in them as largely the result of spontaneous, unplanned entrepreneurial development. As an economist quoted in the Washington Post article points out, Urbanization and modernization are processes that naturally take place.… You can’t force it to happen or have 1,000 places copy the same model. Construction of these so-called ghost cities is likely financed by artificial credit expansion. In other words, people […]

1. This week at Market Urbansim: Private Neighborhoods And The Transformation Of Local Government by Sandy Ikeda In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Thoughts On Today’s Emily Hamilton Vs. Randal O’Toole Cato Discussion by Michael Lewyn O’Toole said high housing prices don’t correlate with “zoning” just with “growth constraints.” But the cities with strict regionwide growth constraints aren’t necessarily high cost cities like New York and Boston, but mid-size, moderately expensive regions like Seattle and Portland. 2. MU Elsewhere Emily Hamilton wrote Rules that wreck housing affordability for the Washington Times, analyzing the White House report on housing affordability President Obama deserves credit for recognizing a serious economic problem that is escaping our attention. What’s happening in Takoma is happening in every expensive city in the country, resulting in lost opportunities for the people who need them the most. Reforms to city land-use regulations would not only improve the lives of local renters, but could also improve economic growth for the whole country. Emily‘s debate with Randal O’Toole is also up at Cato 3. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer is in Los Angeles, and this weekend will be hanging around the California beach towns of Santa Monica, Venice Beach, Manhattan Beach, Long Beach and so on. His three Forbes articles this week were: ‘Friendsgivings’ Are A Growing Urban American Tradition…Could The Fair Housing Act Be Used To Abolish Restrictive Zoning?…and Nativism: The Thread Connecting Progressive NIMBYs With Donald Trump These and countless other examples show the cognitive dissonance of some urban progressives, who blast Trump supporters for their supposed xenophobia and racism, while practicing their own brand of […]

Because of work obligations, I listened to only about a third of today’s Cato Institute discussion on urban sprawl. I heard some of Randall O’Toole’s talk and some of the question-and-answer period. O’Toole said high housing prices don’t correlate with “zoning” just with “growth constraints.” But the cities with strict regionwide growth constraints aren’t necessarily high cost cities like New York and Boston, but mid-size, moderately expensive regions like Seattle and Portland. He says that if land use rules raise housing prices they violate the Fair Housing Act. Maybe this should be the case, but it isn’t. Government can still regulate in ways that raise housing prices, but just have to show reasonable justification for those policies under “disparate impact” doctrine. He also says cities would be less dense without zoning. Is he aware that most city regulations limit density rather than mandating density? O’Toole says growth constraints are why American home ownership rates are lower than in Third World countries and that the natural rate of home ownership is 75 percent. But why are home ownership rates so low in sprawling Sun Belt cities? For example, metro Houston’s home ownership rate is about 59 percent – higher than New York or San Francisco, but lower than Philadelphia or Pittsburgh. The highest home ownership rates are in Rust Belt regions like Akron, I suspect because of low levels of mobility. Some things he gets right: 1) public participation in land use process is harmful because it leads to more restrictions, not less; (2) the mortgage interest deduction doesn’t make much difference in home ownership rates.

Urban Institute Press • 2005 • 494 pages • $32.50 paperback In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Nelson argues that while all levels of American government have been expanding since World War II, people have responded with a spontaneous and massive movement toward local governance. This has taken two main forms. The first is what he calls the “privatization of municipal zoning,” in which city zoning boards grant changes or exemptions to developers in exchange for cash payments or infrastructure improvements. “Zoning has steadily evolved in practice toward a collective private property right. Many municipalities now make zoning a saleable item by imposing large fees for approving zoning changes,” Nelson writes. In one sense, of course, this is simply developers openly buying back property rights that government had previously taken from the free market, and “privatization” may be the wrong word for it. For Nelson, however, it is superior to rigid land-use controls that would prevent investors from using property in the most productive way. Following Ronald Coase, Nelson evidently believes it is more important that a tradable property right exists than who owns it initially. The second spontaneous force toward local governance has been the expansion of private neighborhood associations and the like. According to the author, “By 2004, 18 percent—about 52 million Americans—lived in housing within a homeowner’s association, a condominium, or a cooperative, and very often these private communities were of neighborhood size.” Nelson views both as positive developments on the whole. They are, he argues, a manifestation of a growing disenchantment with the “scientific management” of […]

1. This week at Market Urbansim: The Urban Origins of Liberty by Sandy Ikeda Only in the commercial society of the cities, which then as today attracted the ambitious, the talented, and the misfit, did liberty have a real meaning and substance. Only if you can “vote with your feet,” leave the manor or village to pursue your dreams, or simply travel (and have a reason to travel) from place to place, are you really free. One Reason Why Subsidies Aren’t the (Only) Solution by Michael Lewyn The policy paper points out, however, that HUD’s existing project-based and housing choice vouchers could serve more families if the per-unit cost wasn’t pushed higher and higher by rents rising in the face of barriers to new development.” 2. MU Elsewhere Just another reminder to catch Market Urbanist Emily Hamilton debate Cato’s Randal O’Toole on November 29th in Washington, DC, on the question “Should Urban Areas Grow Up or Out to Keep Housing Affordable” (event details) 3. Where’s Scott? Scott Beyer spent his second week in Los Angeles. He wants before leaving on December 11th to organize a dinner party for the area’s many pro-housing activists, so PM him if you’re interested or know someone who is. He published two articles this week–a 5k-word white paper for the Center for Opportunity Urbanism about San Antonio (pg. 40 of this pdf); and one for Forbes titled Globalism — Not Nativism — Is What Made America’s Cities Great Along with the 1 million undocumented immigrants in L.A. County, there is an estimated 500,000 in New York City, 500,000 in the Bay Area, 400,000 in the Houston area, and 260,000 in greater Miami. Impose mass deportation upon these—some of the nation’s most economically dynamic—metros, and the federal government would be ripping out huge portions of their workforce, customer base and entrepreneurial ecosystem. Scott […]

I was rereading the Obama Administration’s surprisingly market-oriented policy paper on zoning and affordable housing, and saw one good point that I had never really thought about. One common anti-development argument is that government should subsidize housing for the poor instead of allowing the construction of upper-class housing that might eventually filter down to the poor (or cause older middle-class housing to do so). The policy paper points out, however, that “HUD’s existing project-based and housing choice vouchers could serve more families if the per-unit cost wasn’t pushed higher and higher by rents rising in the face of barriers to new development.” In other words, high market rents make subsidies more expensive, which in turn means that government can subsidize fewer units with the same dollar. In other words, high market rents make it harder, not easier, for government to subsidize housing.

In The Road to Serfdom, F. A. Hayek tells us that intellectuals and governments in the twentieth century tragically abandoned the road to liberty in pursuit of collectivist utopias. That road stretched at least as far back as the democratic polis of ancient Greece, but it was not always straight and unbroken. Once, it was completely lost, only to be rediscovered centuries later. The idea of liberty emerged in the struggle between the forces of collectivism and individualism. It is the idea that each of us has a rightful sphere of autonomy in which we may be free from aggression. In politics this manifested itself as liberal democracy, in economics as market competition, and in the broader social realm as scientific advance, artistic expression, and religious tolerance. In his concise masterpiece, Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade, the Belgian historian Henri Pirenne explains just how, long after the fall of the western Roman empire, the liberal idea gradually reemerged and how this was directly tied to the birth of the modern city. The Decline of Cities and Civilization Between AD 400 and 900 cities virtually disappeared from Europe. Even in Rome, which at its height had a population of one million, the population fell to mere thousands – most of whom were either Churchmen or those who served them. Bishops and clerics dominated urban life, while princes, who had little reason to spend time in dreary medieval towns, focused attention on protecting their feudal estates, earning tribute from their vassals, and exploiting the labor of their serfs. Then as now, nobles followed wealth, and in the Middle Ages, as trade among cities dwindled, the basis for wealth went from money to land. Money, liquid and essential for commerce, became superfluous, while control and acquisition of land became […]