Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The needs of the aged are often a political football in disputes over transportation policy. On the one hand, defenders of low-cost parking and other car-oriented policies argue that older people all need cars because they can’t be bothered to walk. On the other hand, smart growth types argue that we will all be too old to drive someday, so we need to end the reign of car dependency. One way of examining the issue is to find out whether seniors in fact drive more than everyone else. Happily, the 2016 American Community Survey comes to our rescue here. In Manhattan where I live, there are just over 129,000 senior-headed households with no car, and just over 36,000 with a vehicle available. So contrary to car-lobby conventional wisdom, only about 22 percent of senior-headed households have a car. How does that compare with other age groups? On the one hand, only about 25,000 out of 200,000, or 12 percent, of millennial-headed households (that is, households headed by someone under 35) have a vehicle. But among Manhattan households headed by persons between 35 and 64, about 28 percent (just over 109,000 out of just over 386,000) have a vehicle- more than senior-headed households, to my surprise. So I rate the “Old People Need Cars” claim as Mostly False: most seniors here in Manhattan don’t have cars, even though they are more likely to own cars than millenials. On the other hand, the latter fact suggests that seniors are rarely physically incapable of using cars.

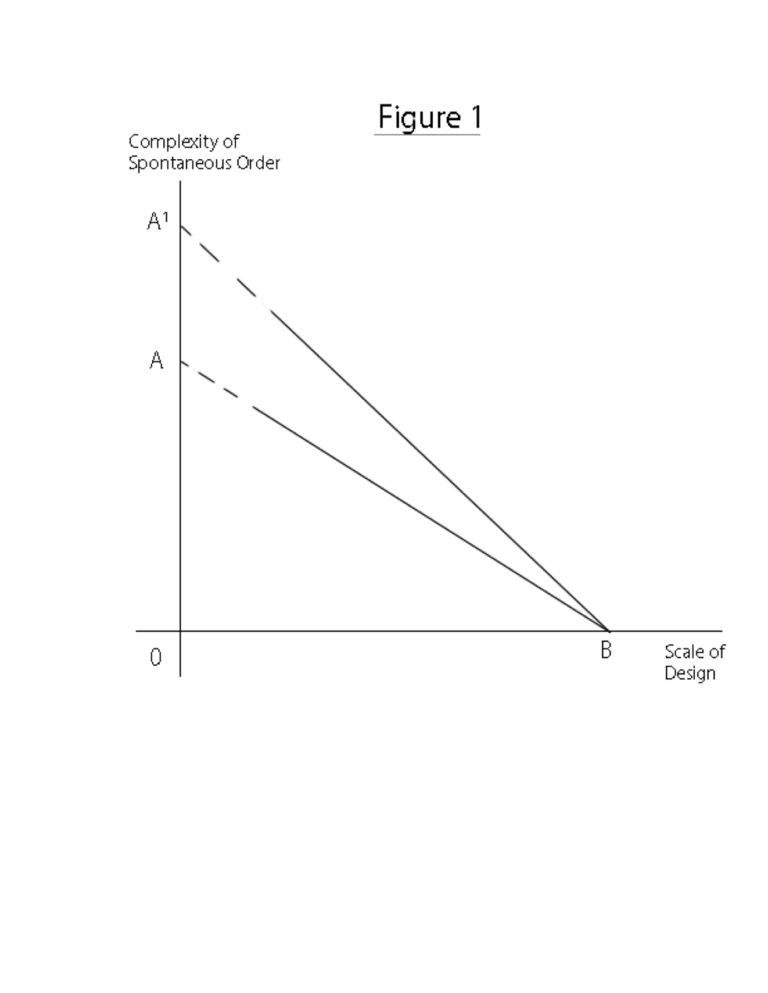

We can visualize the tradeoff between the scale of design and the complexity and spontaneity of a social order as a downward-sloping curve. A sort of “scale-versus-order-possibilities frontier.” In addition to scale and spontaneous order/complexity, a third element I would add to the tradeoff is the passage of time. You can to some extent plan for complementarity, but you can’t really plan for spontaneous complexity and intricacy. [Helpful to bring in capital theory here?] Fortunately, time allows people to some extent to adjust social networks and physical spaces to better complement their own plans, in ways that the designer could not foresee. That is, for any given scale, time lets people figure out novel uses for, or changes to, the space as originally designed. Those unthought-of uses constitute an increase in the level of complexity in a spontaneous order. Over time, then, the frontier can shift outward. Figure 1 reflects these relations: The scale of a structure and the designed or planned uses of the space within that structure are of course two different things. Increasing the dimensions of a room doesn’t necessarily mean the elements that go into its design become more complex. But to keep things simple, Figure 1 treats scale and design as highly positively correlated. [Is this necessary?] Thus, as scale increases so do the designed elements – you move from point A to point B – and together they decrease the potential for spontaneous order. [But think about the tradeoff between scale and order, keeping design constant. Just increasing scale does seem to increase the designed/planned element in a previously undesigned space.] Then, as time passes, the frontier shifts up from AB to A’B, where point B represents the case where the structure occupies100% of the relevant action space. So for any given scale, the […]

The Bible says again and again and again to “love the stranger”. Although this phrase has been interpreted in a variety of different ways, one highly plausible interpretation of this maxim is that we should be at least somewhat hospitable to newcomers and temporary sojourners in our midst. But American land use and transportation regulations seem to be motivated by hostility to “strangers” (or, as they are more perjoratively termed, “transients”). For example, the most privileged uses in zoning are the most permanent: single-family houses and businesses tend to be the least controversial land uses, while the most transient-oriented land uses tend to be the most controversial. Owners of single-family houses try to zone out apartments because renters are “transient”, and homeowners and renters in turn may ally try to zone out hotels and other forms of short-term rental because the users of these services are even more ‘transient” than renters. Street design often seems hostile to transients as well; a visitor to a city is least likely to be disoriented in a place where one can guess a place’s location based on an address. For example, if you are going to 1125 M Street, SW, in Washington, DC you know that your destination is near the corner of 11th and M Streets. Other gridded areas are a little less legible, but even so you can somewhat guess where you are going if you know a street name or two. By contrast, newer suburbs often tend to be much less legible to visitors: for example, in suburban Atlanta, there is no street grid and the proliferation of cul-de-sacs makes navigation confusing for visitors.

In most of my discussions of Houston here on the blog, I have always been quick to hedge that the city still subsidizes a system of quasi-private deed restrictions that control land use and that this is a bad thing. After reading Bernard Siegan’s sleeper market urbanist classic, “Land Use Without Zoning,” I am less sure of this position. Toward this end, I’d like to argue a somewhat contrarian case: subsidizing private deed restrictions, as is the case in Houston, is a good idea insomuch as it defrays resident demand for more restrictive citywide land-use controls. For those of you who haven’t read my last four or five wonky blog posts on land-use regulations in Houston (what else could you possibly be doing?), here is a quick refresher. Houston doesn’t have conventional Euclidean zoning. Residents voted it down three times. However, Houston does have standard subdivision and setback controls, which serve to reduce densities. The city also enforces high minimum parking requirements outside of downtown. On top of these standard land-use regulations, the city heavily relies on private deed restrictions. Also known as restrictive covenants, these are essentially legal agreements among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property, often set up by a developer and signed onto as a condition for buying a home in a particular neighborhood. In most cities, deed restrictions cover superfluous lifestyle preferences not already covered by zoning, including lawn maintenance and permitted architectural styles. In Houston, however, these perform most of the functions normally covered by zoning, regulating issues such as permissible land uses, minimum lot sizes, and densities. Houston’s deed restrictions are also different in that they are heavily subsidized by the city. In most cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by parties to a deed, typically organized as a […]

New York politicians’ attacks on Airbnb are now getting national press; they argue that because Airbnb units could be used for long-term rentals, Airbnb reduces the housing supply and thus raises rents. But just as a matter of principle, this claim leads to absurd results. The logic underlying the claim is: a housing unit that is used for short-term rentals such as Airbnb could be easily used for long-term rentals. Thus, Airbnb reduces the long-term housing supply. But this argument proves too much. If you own a house, your house could also be used for long-term rentals. If you have a spare room, you could rent out that spare room. And even if you rent out every room in the house, your house sits on land that could be used for a much larger number of rental units. Since there are far more single-family houses than there are Airbnb units, bulldozing every house in the city would increase housing supply to a much greater extent than would outlawing Airbnb. Does this mean the city should bulldoze your house to build more rental housing?

I just spoke at a conference at Fordham on market urbanism and how it is similar to (and different from) new urbanism. The speech can be found here.

First of all, Jacobs observed that the artist abstracts from life, with all its “inclusiveness” and “literally endless intricacy.” Many architects, especially those with great ambition, seem to treat urban environments as merely a canvas for their works of genius, which if not already blank needs to be wiped clean before getting to work. The good ones at least try to take into account how their constructions fit or don’t fit into the existing built environment and how real people might actually use them. But whether you’re an architect or an economist, predicting how people will respond to a change is a pretty iffy thing. From my perspective that iffiness comes from two factors: complexity and radical ignorance. Complexity in this context means that the interactions among people are so numerous or varied or changeable that the costs of being aware of all of them is too high for anyone to calculate. Hayek defines the degree of complexity in terms of the “minimum number of elements of which an instance of the pattern consists in order to exhibit all the characteristic attributes of the class of patterns in question…” (Hayek 1964). In a world with only a few variables, such as those described in a high-school algebra problem, it is possible to have all the knowledge you need to get the correct answer. In the real world, however, the number of relevant variables is too large, that is the number of ever-changing interactions among people in society is so large, and our cognitive powers are too limited to do that. Compared to the vast complexity of the social order, predicting this week’s weather is a pretty simple matter. Radical ignorance means being unaware of information that would be relevant to making a decision, not because the cost is too high, […]

The Center for Market Urbanism released its first policy report in partnership with Abundant Housing Los Angeles. The paper, written by The Center for Market Urbanism’s Nolan Gray and Emily Hamilton, recommends eliminating minimum parking requirements as part of DTLA 2040, a process which will update both the Central City and Central City North community plans. The draft concept for the DTLA 2040 plan calls for eliminating parking requirements for the Central City and Central City North neighborhoods. This would build upon the success of Los Angeles’ adaptive reuse, allowing new developments to facilitate affordable, dense, walkable neighborhoods. The paper discusses the history of parking requirements, burdens and damage caused by current parking requirements, and benefits of reforms: Combined with demand-based pricing for on-street parking, the elimination of parking requirements will allow for downtown neighborhoods that are more walkable while also reducing congestion for drivers. Read the Center for Market Urbanism/Abundant Housing LA Policy Paper here The Center for Market Urbanism is a 501c3 organization dedicated to expanding choice, affordability, and prosperity in cities through smart reforms to U.S. land-use regulation. Abundant Housing LA is 501c3 organization which is committed to advocating for more housing. We want lower rents and a more sustainable and prosperous region, where everyone has more choices of where to live and how to pursue their dreams. LA is one of the most diverse, vibrant cities in America, and we are fighting to keep it that way for current Angelenos, our children, and those who come here to pursue their dreams.

Nashville has enjoyed some of the country’s fastest job growth for several years as healthcare and tech startups have made the city home. Unsurprisingly, this economic boom has coincided with a large increase in population, greater demand for real estate, and rising house prices. But Nashville’s policy environment has moderated price increases relative to what many in-demand cities have experienced. Nashville policy has made it possible for housing developers to build both up and out in response to this new demand. However, an expansion of historic preservation efforts that have so far failed to prevent demographic change could stall the new housing supply that has maintained the city’s relative affordability. Nashville’s experience offers three lessons for other cities: 1. Legalize Housing and It Will Be Built Since 2010 the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area has grown by more than 400,000 residents, or 20 percent. Davidson County, home to Nashville at the center of the region, has grown by nearly 65,000 people, or 10 percent. Like other Southern cities, its easy to build new suburban housing in the Nashville region, and most of this population growth has been accommodated by building out. What’s unusual is that Nashville is also accommodating significant infill. In 2010 the city enacted a downtown rezoning. It eliminated parking requirements and increased by-right height limits. The new code is essentially a form-based code. Nearly all uses except for industrial are allowed in the center city. Dozens of new office, hotel, and residential towers have delivered since the new code was implemented, and many more are under construction. Since the new code has been in place, population in the two census tracts affected by upzoning has grown from about 7,500 to about 10,000. Forthcoming research from my colleague Salim Furth shows that Nashville’s recent low-density growth has been comparable to what we’d expect […]

As Jacobs explains in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works that are under the control of the artist…the essence of the process is disciplined, highly discriminatory selectivity from life. In relation to the inclusiveness and the literally endless intricacy of life, art is arbitrary, symbolic and abstracted…To approach a city, or even a city neighborhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, is to make the mistake of attempting to substitute art for life. The results of such profound confusion between art and life are neither art nor life. They are taxidermy.” (1961: 372-3, emphasis original) So how do we avoid turning the results of urban design into taxidermy and killing off a city by planning? I think the short answer is that we avoid it by recognizing that there’s a tradeoff between the scale of a design and the degree of spontaneity, complexity, and intricacy in the resulting social order that the design allows. Now, saying that a city cannot be a work of art doesn’t mean of course that a city cannot be beautiful or that deliberate design can never enhance that beauty. But I am suggesting that beauty that is designed as a work of art is fundamentally different from the undersigned beauty that emerges from a lifetime of experience. The skillfully made-up face of a fashion model and the face of a 90-year-old grandmother are both beautiful, but in profoundly different ways. Niels Gron, quoted in Gerard Koeppel’s City of a Grid: How New York Became New York: Before I came to this country, and in all the time […]