Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Desire for Density is a new framework explaining how market prices form a desire path showing where the market could deliver more affordable housing than it presently is.?

In this interview I talk to Onésimo Flores, Founder of Jetty, a (sort-of) microtransit company from Mexico City. Marcos Schlickmann: Thank you for participating in this interview. Please introduce yourself and talk a little bit about how Jetty came to life and what is your idea behind this project. Onésimo Flores: I’m Onésimo Flores, the founder of Jetty. I have a PhD in urban planning from MIT and a master’s in public policy from Harvard. I graduated in Law from the Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico. The idea of Jetty came about by contrasting a conflicting approach to regulation in public transportation in a place like Mexico. On one end of the spectrum, a you have a very tightly-regulated, low-quality, scarce public transport service, most of it operated by private, informal, artisanal, minibus operators, and on the other hand, ride-hailing apps, taxi apps, that had emerged not only Uber but several others, that enjoy a lot of regulatory leeway in terms of freedom to set their fares, to operate anywhere, to open the market to private individuals with spare time and spare vehicles. So, in that context, the hypothesis was that, in a way applications like Uber have made it possible to standardize a level of service: people can know what to expect, know that somebody will be held accountable if something goes wrong, know the basics of the trip, the fare and the rated quality of the driver. The level of information the passengers will get is standardized no matter who the supplier of the services is. So, the hypothesis in Jetty is that we can do something similar for collective transportation without relinquishing the economies of scale of using larger vehicles, but we do give the public access to the service improvements made possible by technology. MS: Talk a little […]

The Carnegie Library in Washington, D.C. is now home to the world’s newest Apple Store following an expensive rehabilitation funded by the retailer. Originally built as a public library in 1903, it reopened its doors to the public on May 11, 2019 following decades of disuse, neglect, and a slew of failed attempts to repurpose the building as a museum. While some are fretting that a historic building owned by the city has been turned over to commercial use, we can rest assured that the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., the current leaseholder to the building, made the right decision. More than fifteen years ago, Niskanen Center founder Jerry Taylor and his then-colleague at the Cato Institute, Peter Van Doren, had a novel proposal to solve an intractable political dispute about the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), a wilderness area in northeast Alaska that is home to large populations of wildlife and vast, untapped petroleum deposits. In the early 2000s, the Bush Administration proposed opening the refuge to oil drilling in the wake of rising crude oil prices. Naturally, the usual suspects came out in favor or against the proposal. Environmentalist detractors worried that a pristine wildlife area could be ruined by any drilling and the possibility of leaky pipelines. Advocates, on the other hand, claimed only a tiny sliver of land was needed to extract billions of dollars of oil and the refuge would remain largely untouched. The benefits of oil drilling, proponents argued, would be widely shared because oil is used in so many parts of economy. Taylor and Van Doren’s proposal was simple: the federal government should give ANWR, in its entirety, to the Sierra Club or some other environmentalist group, including full rights to use or transfer the land as they see fit. While the Sierra […]

1. Recently at Market Urbanism A great new paper on how government fights walking by Michael Lewyn Many readers of this blog know that government subsidizes driving- not just through road spending, but also through land use regulations that make walking and transit use inconvenient and dangerous. Gregory Shill, a professor at the University of Iowa College of Law, has written an excellent new paper that goes even further. Why Japanese Zoning More Liberal Than US Zoning by Nolan Gray Why did U.S. zoning end up so much more restrictive than Japanese zoning? To frame the puzzle a different way, why did U.S. and Japanese land-use regulation—which both started off quite liberal—diverge so dramatically in terms of restrictiveness? Democratic Candidates on Housing by Jeff Fong Anti poverty programs have been taking center stage as the 2020 Democratic primary heats up. Proposals from Kamala Harris and Corey Booker target high housing costs for renters and make for an interesting set of ideas. These plans, however, have major shortcomings and fail to address the fundamental problem of supply constraints in high cost housing markets. Against Spot Text Amendments by Nolan Gray As zoning has become more restrictive over time, the need for “safety valve” mechanisms—which give developers flexibility within standard zoning rules—has grown exponentially. What Should I Read to Understand Zoning? by Nolan Gray We are blessed and cursed to live in times in which most smart people are expected to have an opinion on zoning. Blessed, in that zoning is arguably the single most important institution shaping where we live, how we move around, and who we meet. Cursed, in that zoning is notoriously obtuse, with zoning ordinances often cloaked in jargon, hidden away in PDFs, and completely different city-to-city. Homeownership and the Warren Housing Bill by Emily Hamilton Elizabeth Warren’s housing bill has received a lot of love from those who favor […]

Some commentators are slightly agog over an academic paper by Andres Rodrieguz-Pose and Michael Storper; Richard Florida writes that they shows that ” the effect of [housing] supply has been blown far out of proportion. ” Most of this paper isn’t really about the effect of housing supply on prices at all. Instead, the first 80 percent of the paper seems to argue that it makes no sense for low-skilled domestic workers to live in cities, because “Several decades ago mid-skilled work was clustered in big cities, while low-skilled work was most prevalent in the countryside. No longer; the mid-skilled jobs that remain are more likely to be found in rural areas than in urban ones.” (p. 20). The authors’ attack on upzoning is in the last few pages, and is based on broad, sweeping generalizations rather than actual data. First, they say that upzoning “would very likely involve replacing older and lower-quality housing stock in areas highly favoured by the market, effectively decreasing housing supply for lower income households in desirable areas.” (p. 30). They cite no source or data for this assertion- just pure conjecture. What’s wrong with their claim? First, such gentrification happens without upzoning; for example, in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, gentrification occurred through renovation of existing structures, rather than new, taller buildings- and of course places where new construction is politically difficult (such as San Francisco and Manhattan) are notorious for gentrification. Second, it assumes that new housing inevitably replaces older housing, rather than, say, vacant lots- an obvious overgeneralization.. Second, they rely on the “but we’re already building new housing!” argument. They cite a paywalled newpaper article to support this statement: “rents are now declining for the highest earners while continuing to increase for the poorest in San Francisco, Atlanta, Nashville, Chicago, Philadelphia, Denver, Pittsburgh, […]

Zoning regulations inflict great harm. But it is difficult for Americans to imagine the cost of zoning in Indian cities. Delhi is one of the most crowded cities in the world, and there is great demand for floor space. But real estate developers are not allowed to build tall buildings.

One common argument against tall buildings is that they reduce street life, because the most expensive high-rises have gyms and other amenities that cause people to stay inside the buildings rather than using the street. Because Manhattan has plenty of high-rises and plenty of street life, I have always thought this was a dumb argument. But until recently I’ve never thought of any way to prove or disprove the argument empirically- until now. It seems to me that if high-rises were bad for street life, places with expensive high-rises would have lower Walkscores than other neighborhoods; I reason that if high-rise residents stayed inside rather than going outside, they would be surrounded by fewer businesses than low-rise neighborhoods. So do high-rises generally have lower Walkscores? Not in dense areas; for example, 432 Park Avenue, one of Manhattan’s most expensive buildings, has a Walkscore of 98. Similarly, Boston’s Millenium Tower, a 60-story residential skyscraper, has a Walkscore of 96.

We are blessed and cursed to live in times in which most smart people are expected to have an opinion on zoning. Blessed, in that zoning is arguably the single most important institution shaping where we live, how we move around, and who we meet. Cursed, in that zoning is notoriously obtuse, with zoning ordinances often cloaked in jargon, hidden away in PDFs, and completely different city-to-city. Given this unusual state of affairs, I’m often asked, “What should I read to understand zoning?” To answer this question, I have put together a list of books for the zoning-curious. These have been broken out into three buckets: “Introductory” texts largely lay out the general challenges facing cities, with—at most—high-level discussions of zoning. Most people casually interested in cities can stop here. “Intermediate” texts address zoning specifically, explaining how it works at a general level. These texts are best for people who know a thing or two about cities but would like to learn more about zoning specifically. “Advanced” texts represent the outer frontier of zoning knowledge. While possibly too difficult or too deep into the weeds to be of interest to most lay observers, these texts should be treated as essential among professional planners, urban economists, and urban designers. Before I start, a few obligatory qualifications: First, this not an exhaustive list. There were many great books that I left out in order to keep this list focused. Maybe you feel very strongly that I shouldn’t have left a particular book out. That’s great! Share it in the comments below. Second, while these books will give you a framework for interpreting zoning, they’re no substitute for understanding the way zoning works in your specific city. The only way to get that knowledge is to follow your local planning journalists, attend local […]

Elizabeth Warren’s housing bill has received a lot of love from those who favor of land use liberalization. Like Cory Booker’s housing bill, the Warren bill would seek to encourage state and local land use reform using federal grants as an incentive. Warren’s bill would significantly increase funding for the Housing Trust Fund and provide a small increase in allocations for public housing maintenance. However, Warren’s bill also includes new subsidies to homeownership and policies that could reduce the production of new renter-occupied housing relative to owner-occupied housing. There’s a trade off in housing policy between promoting homeownership as a wealth-building tool and promoting affordability that politicians, including Warren, have failed to confront. Rather than promoting housing affordability by rolling back policies that subsidize homeowners at the expense of renters, Warren’s bill seeks to reduce exclusionary, suburban zoning at the same time it introduces new policies to incentivize homeownership. First, Warren’s bill would require most foreclosed homes to be sold to new owner-occupants, rather than to landlords who would rent them out. The intention of the bill is to prevent institutional investors from profiting from foreclosures, but this approach has a strong anti-renter bias. When changes in economic conditions, demographics, or preferences lead to an increase in the proportion of Americans who want to rent rather than own, this policy would stand in the way of homes being adapted to meet new needs. Second, the bill would provide down payment assistance to first-time homebuyers who live in, or were displaced from, historically redlined neighborhoods. All levels of government have played horrific roles in excluding minorities from white neighborhoods and subsidizing wealth-building through home equity for white households alone. The victims of these policies deserve to be compensated for this unfairness. The Justice Department and the Department of Housing and Urban […]

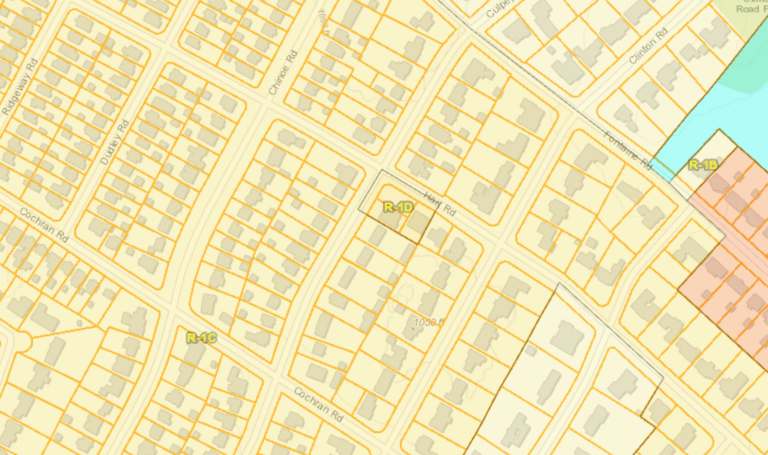

As zoning has become more restrictive over time, the need for “safety valve” mechanisms—which give developers flexibility within standard zoning rules—has grown exponentially. U.S. zoning officially has two such regulatory relief mechanisms: variances and special permits. Variances generally provide flexibility on bulk rules (e.g. setbacks, lot sizes) in exceptional cases where following the rules would entail “undue hardship.” Special permits (also called “conditional use permits”) generally provide flexibility on use rules in cases where otherwise undesirable uses may be appropriate or where their impacts can be mitigated. An extreme grade change is one reason why a lot might receive a variance, as enforcing the standard setback rules could make development impossible. Parking garages commonly require special use permits, since they can generate large negative externalities if poorly designed. Common conditions for permit approval include landscaping or siting the entrance in a way that minimizes congestion. (Wikipedia/Steve Morgan) In addition to these traditional, formal options, there’s a third, informal relief mechanism: spot zoning. This is the practice of changing the zoning map for an individual lot, redistricting it into another existing zone. Spot zonings are typically administered where the present zoning is unreasonable, but the conditions needed for a variance, special permit, or a full neighborhood rezoning aren’t. In many states, spot zonings are technically illegal. The thinking is that they are arbitrary in that they treat similarly situated lots differently. But in practice, many planning offices tolerate them, usually bundling in a few nearby similarly situated lots to avoid legal challenge. An example of a spot zoning. Variances, special permits, and spot zonings are generally considered to be the standard outlets for relief from zoning. But there’s a fourth mechanism that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been recognized: let’s call it the “spot text amendment.” Like spot zonings, spot text amendments […]