Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

A pure libertarian might argue that in an ideal world, there’d be no need for government-subsidized housing for low- and moderate-income households. Nevertheless, it seems to me that in the world we actually live in, even people generally opposed to the welfare state should favor more such housing. This is so for several reasons. First, government raises the cost of housing through a wide variety of regulations- some justified (e.g. building codes necessary for safety), some not-so-justified (e.g. exclusionary zoning). These regulations, by raising the cost of housing, effectively take money from all households. And because these restrictions aren’t based on ability to pay, they are especially painful for low-income households. Public housing and similar programs, rather than being a subsidy to the undeserving poor, are merely compensation for this act of plunder. Second, even if the United States abolished zoning tomorrow, it might take decades for housing supply to increase enough to bring rents down. So in the interim, lower-income households would still be suffering from the effects of zoning, and would deserve compensation just as much as they do under the status quo. Third, even if the United States abolished zoning and similar restrictions tomorrow, public health and safety might support certain restrictions that nevertheless increase the cost of housing- for example, some basic safety protections in building codes. It seems to me that as a matter of justice, government should not be forcing people into homelessness, so government should subsidize housing in order to make up for the costs imposed by even the most legitimate regulations. Finally, even if there were no housing-related regulations at all, the cost of land would create a floor under housing costs, which means some people would be homeless without government support. So if homelessness creates harmful social externalities of any kind, […]

How much should we blame planning for the degree to which cities sprawl? As much time as we (justifiably) spend here on this blog explaining how conventional U.S. planning drives excessive sprawl, it’s worth periodically remembering that, at the end of the day, the actual extent of the horizontal expansion of cities is largely outside the control of urban planning. Consider Houston. Whenever I say anything nice about Houston’s relatively liberal approach to land-use regulation, someone invariably comments some variation of the following: “Yes, that’s all well and good in theory. But in practice, heavily regulated cities like Boston are far more urban and walkable, so maybe relaxed land-use regulations aren’t so great.” Indeed, most of Houston is classic sprawl. But this begs the question: to what extent can urban planning policy be blamed for sprawl? The urban economist Jan Brueckner, drawing on an extensive literature, distinguishes between the “fundamental forces” that naturally drive urban growth outward and the market failures that push this growth beyond what might occur in an appropriately regulated market. (For the purposes of this post, I’ll be using “sprawl” and “horizontal urban expansion” interchangeably. In the same paper, Brueckner thoughtfully distinguishes the two.) The latter, urban planners can address. The former, not so much. Let’s look first at the “fundamental” variables that planners have little to no control over. Brueckner identifies three: population growth, rising income, and falling commuting costs. The first variable is obvious: as cities grow, demand for all housing goes up, and some of that housing goes out on the periphery regardless of planning policy. Metropolises like Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta are currently experiencing 2% population growth every year, meaning they are on track to double in population in the next 35 years. You would expect a lot of horizontal expansion, all else […]

I recently discovered a new logical fallacy: the “Morton’s Fork” fallacy. This argument is one in which contradictory observations lead to the same conclusion. For example, if I argue that new housing near public transit is bad because it (1) spurs gentrification by bringing rich people into the neighborhood and (2) increases crime by bringing poor people into the neighborhood, I am engaging in this fallacy. Similarly, I have heard arguments that new housing is bad because it (1) brings down property values and (2) increases property values. In such situations, it is sometimes possible that one of the two claims could be true, but it is unlikely that both claims could be true.

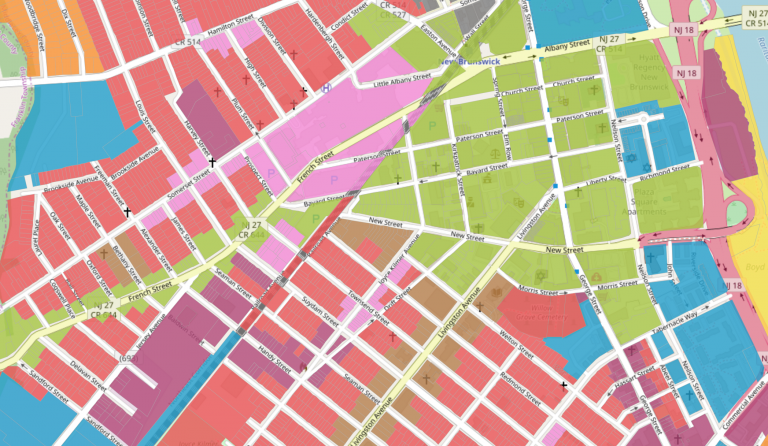

In most of my discussions of Houston here on the blog, I have always been quick to hedge that the city still subsidizes a system of quasi-private deed restrictions that control land use and that this is a bad thing. After reading Bernard Siegan’s sleeper market urbanist classic, “Land Use Without Zoning,” I am less sure of this position. Toward this end, I’d like to argue a somewhat contrarian case: subsidizing private deed restrictions, as is the case in Houston, is a good idea insomuch as it defrays resident demand for more restrictive citywide land-use controls. For those of you who haven’t read my last four or five wonky blog posts on land-use regulations in Houston (what else could you possibly be doing?), here is a quick refresher. Houston doesn’t have conventional Euclidean zoning. Residents voted it down three times. However, Houston does have standard subdivision and setback controls, which serve to reduce densities. The city also enforces high minimum parking requirements outside of downtown. On top of these standard land-use regulations, the city heavily relies on private deed restrictions. Also known as restrictive covenants, these are essentially legal agreements among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property, often set up by a developer and signed onto as a condition for buying a home in a particular neighborhood. In most cities, deed restrictions cover superfluous lifestyle preferences not already covered by zoning, including lawn maintenance and permitted architectural styles. In Houston, however, these perform most of the functions normally covered by zoning, regulating issues such as permissible land uses, minimum lot sizes, and densities. Houston’s deed restrictions are also different in that they are heavily subsidized by the city. In most cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by parties to a deed, typically organized as a […]

Houston doesn’t have zoning. As I have written about previously here on the blog, this doesn’t mean nearly as much as you would think. Sure, Houston’s municipal government doesn’t segregate uses or expressly regulate densities. But as my Market Urbanism colleague Michael Lewyn has documented, city officials do regulate lot sizes, setbacks, and parking requirements. They also enforce private deed restrictions, which blanket many of the city’s residential neighborhoods. A deed restriction is a legal agreement among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property. In most cities, deed restrictions are purely private and often fairly marginal, adding rules on top of zoning that property owners must follow. But in Houston, deed restrictions do most of the heavy lifting typically covered by zoning, including delineating permissible uses and design standards. Whenever I point out that Houston has relatively light land-use regulations (and is enjoying the benefits), folks often respond that the city’s deed restrictions are basically zoning. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Before I turn to the essential differences, it’s worth first observing how Houston’s deed restrictions are like any other city’s zoning. First, like zoning, Houston’s deed restrictions are almost universally designed to prop up the values of single-family houses. Despite the weak evidence for a use segregation-property values connection, this justification for zoning goes back to the program’s roots in the 1920s. Many of Houston’s nicest residential neighborhoods, like River Oaks and Tanglewood, follow this line of thinking, enforcing tight deed restrictions on residents that come out looking a lot like zoned neighborhoods in nearby municipalities like Bellaire and Jersey Village. Second, both zoning and Houston’s deed restrictions are enforced by government officials at taxpayer expense. In most other cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by a private group like a homeowners association, […]

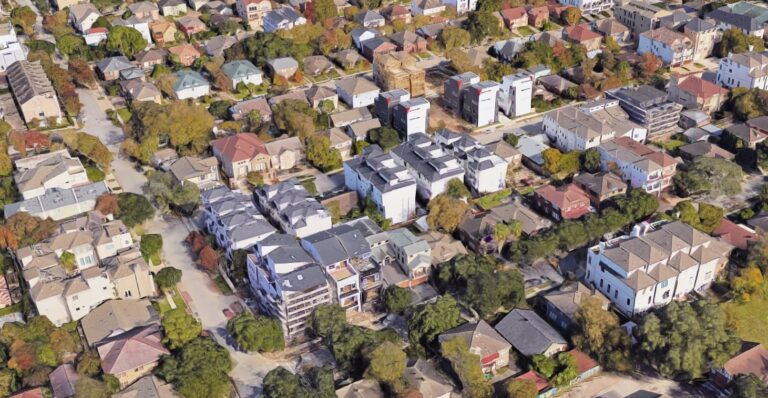

The great failing of modern land-use regulation is the failure to allow densities to naturally change over time. Let me explain. Imagine you are trying to sell a property you own in a desirable inner suburban neighborhood in your town. The lot is 4,000 square feet and hosts an old 4,000 square-foot home. There is incredible demand for housing in this area; perhaps the schools are good, or the amenities are nice, or the neighborhood sits adjacent to a major jobs center, meaning that residents can walk to work. I’ll leave the reasons to you. Who do you sell it to? You have at least two options: First, you could sell it to a wealthy individual, who would use the entire property as his home. He is willing to pay the market rate for single-family homes like this, which in this case is $300,000. Under current financing, he would likely have a monthly mortgage payment in the ballpark of $1,300. Second, you could sell it to a developer who intends to subdivide the house into four 1,000 square foot one-bedroom apartments, renting each of them at a market rate of $500 to service workers who commute to downtown. After factoring in expenses, her annual net operating income would be around $20,160. Assuming a multifamily cap rate of 6.0.%, this means that she could pay up to $336,000 for your property. Based on this analysis, who do you sell it to? The answer is obvious: you will sell it to the multifamily developer who will subdivide and rent out the house, not necessarily because you’re a bleeding heart urbanist, but in order to maximize your earnings. As rents in the area rise, the pressure to sell to a buyer who would densify the property will only grow. The prospective mansion buyer […]

In my regular discussions of U.S. zoning, I often hear a defense that goes something like this: “You may have concerns about zoning, but it sure is popular with the American people. After all, every state has approved of zoning and virtually every city in the country has implemented zoning.” One of two implications might be drawn from this defense of Euclidean zoning: First, perhaps conventional zoning critics are missing some redeeming benefit that obviates its many costs. Second, like it or not, we live in a democratic country and zoning as it exists today is evidently the will of the people and thus deserves your respect. The first possible interpretation is vague and unsatisfying. The second possible interpretation, however, is what I take to really be at the heart of this defense. After all, Americans love to make “love it or leave it” arguments when they’re in the temporary majority on a policy. But is Euclidean zoning actually popular? The evidence for any kind of mass support for zoning in the early days is surprisingly weak. Despite the revolutionary impact that zoning would have on how cities operate, many cities quietly adopted zoning through administrative means. Occasionally city councils would design and adopt zoning regimes on their own, but often they would simply authorize the local executive to establish and staff a zoning commission. Houston was among the only major U.S. city to put zoning to a public vote—a surefire way to gauge popularity, if it were there—and it was rejected in all five referendums. In the most recent referendum in 1995, low-income and minority residents voted overwhelmingly against zoning. Houston lacks zoning to this day. Meanwhile, the major proponents of early zoning programs in cities like New York and Chicago were business groups and elite philanthropists. Where votes were […]

Suburb: Planning Politics and the Public Interest is a scholarly book about planning politics in Montgomery County, a (mostly) affluent suburb of Washington, D.C. The book contains chapters on redevelopment of inner ring, transit-friendly areas such as Friendship Heights and Silver Spring, but also discusses outer suburbs and the county’s agricultural areas. From my perspective, the most interesting section of the book was the chapter on Friendship Heights and Bethesda, two inner-ring areas near subway stops. When landowners proposed to redevelop these areas, the planning staff actually downzoned them (p. 56)- and NIMBYs fought the planning board, arguing that even more downzoning was necessary to prevent unwelcome development. These downzoning decisions were based on the staff’s “transportation capacity analysis”- the idea that an area’s roads can only support X feet of additional development. For example, Hanson writes that Friendship Heights “could support only 1.6 million square feet of additional development.” (p. 62). Similarly, he writes that Bethesda’s “roads and transit could handle only 12 million square feet of new development at an acceptable level of service.” (p. 75) Thus, planning staff artificially limited development based on “level of service “(LOS) . “Level of service” is a concept used to grade automobile traffic; where traffic is free-flowing the LOS is A. But the idea that development is inappropriate in low-LOS places seems a bit inconsistent with my experience. Bethesda and Friendship Heights zip codes have about 5000-10,000 people per square mile; many places with far more density seem to function adequately. For example, Kew Gardens Hills in central Queens has 27,000 people per square mile, relies on bus service, and yet seems to be a moderately popular area. Moreover, the use of LOS to cap density has a variety of other negative effects. First, places with free-flowing traffic tend to be dangerous for […]

The adoption of zoning as a means of preventing external costs led to inefficient use of land and caused many individuals to suffer great unfairness.

by Samuel R Staley Before the twentieth century land-use and housing disputes were largely dealt with through courts using the common-law principle of nuisance. In essence if your neighbor put a building, factory, or house on his property in a way that created a measurable and tangible harm, courts could intervene on behalf of a complainant to force compensation or stop the action. This pro-property rights approach maximized liberty and minimized the ability of citizens and elected officials to politicize the development process. This changed with the Progressive movement. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Progressives argued that government should become more professional. Rather than being limited, government should use its resources to pursue the “public interest,” loosely defined as whatever the general public decided through democratic processes was the proper scope of government. Legislatures and, by extension, city commissions made up of elected citizens would set policy and goals while a cadre of trained professionals would use the techniques of scientific management to implement policies. One of the leading Progressives of the day, Woodrow Wilson, was skeptical of the value of elected bodies such as Congress because they interfered with scientific management of government. While many in the twenty-first century might be tempted to dismiss this public-interest view of government—indeed an entire academic subdiscipline, Public Choice, has emerged to demonstrate the foibles of governments and explore “government failure”—Progressive ideas held a lot of appeal at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition to national concerns over industries such as oil, steel, and railroads, local governments were rife with corruption, waste, and inefficiency. Reforms, such as the city-manager form of government, civil-service exams, and in some cases even municipal ownership of utilities, were thought to provide more transparency and accountability than the patronage-laden times of political bosses. (Today municipal […]